Abstract: In this piece, we briefly look over the history of Ripple and examine various disputes between the founders and partner companies, typically over control of XRP tokens. We then explore elements of the technology behind Ripple. We conclude that the apparent distributed consensus mechanism doesn’t serve a clear purpose, because the default behaviour of Rippled nodes effectively hands full control over updating the ledger to the Ripple.com server. Therefore, in our view, Ripple does not appear to share many of the potentially interesting characteristics crypto tokens like Bitcoin or Ethereum may have, at least from a technical perspective.

Jed McCaleb (left) joined Ripple in 2011. Chris Larsen (right) joined the company in 2012. (Source: BitMEX Research)

Please click here to download a pdf version of this report

Introduction

On 4 January 2018, the Ripple (XRP) price reached a high of $3.31, an incredible gain of 51,709% since the start of 2017. This represented a market capitalization of $331 billion, putting Ripple’s valuation in the same league as Google, Apple, Facebook, Alibaba, and Amazon — the largest tech giants in the world. According to Forbes, Chris Larsen, the executive chairman of Ripple, owns 17% of the company and controls 5.19 billion XRP, worth around $50 billion at the time of the peak, making him one of the richest people in the world. Despite this incredible valuation, many of the market participants do not appear to know much about Ripple’s history or the technology behind it. In this piece, we provide an overview of the history of Ripple and look at some of its technical underpinnings.

History of Ripple

RipplePay: 2004 to 2012

Ryan Fugger founded a company he called RipplePay in 2004. The core idea behind the protocol was a peer-to-peer trust network of financial relations that would replace banks.

The RipplePay logo during that period of the company’s existence. (Source: Ripplepay.com)

RipplePay’s basic theory was as follows:

- All banks do is make and receive loans. A bank deposit is a loan to the bank from the customer.

- A payment from Bob to Alice in the traditional banking system is simply an update to their respective loan balances to the bank, with Bob’s loan to the bank declining slightly and Alice’s increasing slightly.

- RipplePay held that one could replace banks by creating a peer-to-peer trust network in which individuals could directly loan each other, and alterations to these loan balances enable payments.

- Payments, then, are simply updates to these loan balances, provided the system can find a path of relationships from the payer to the recipient.

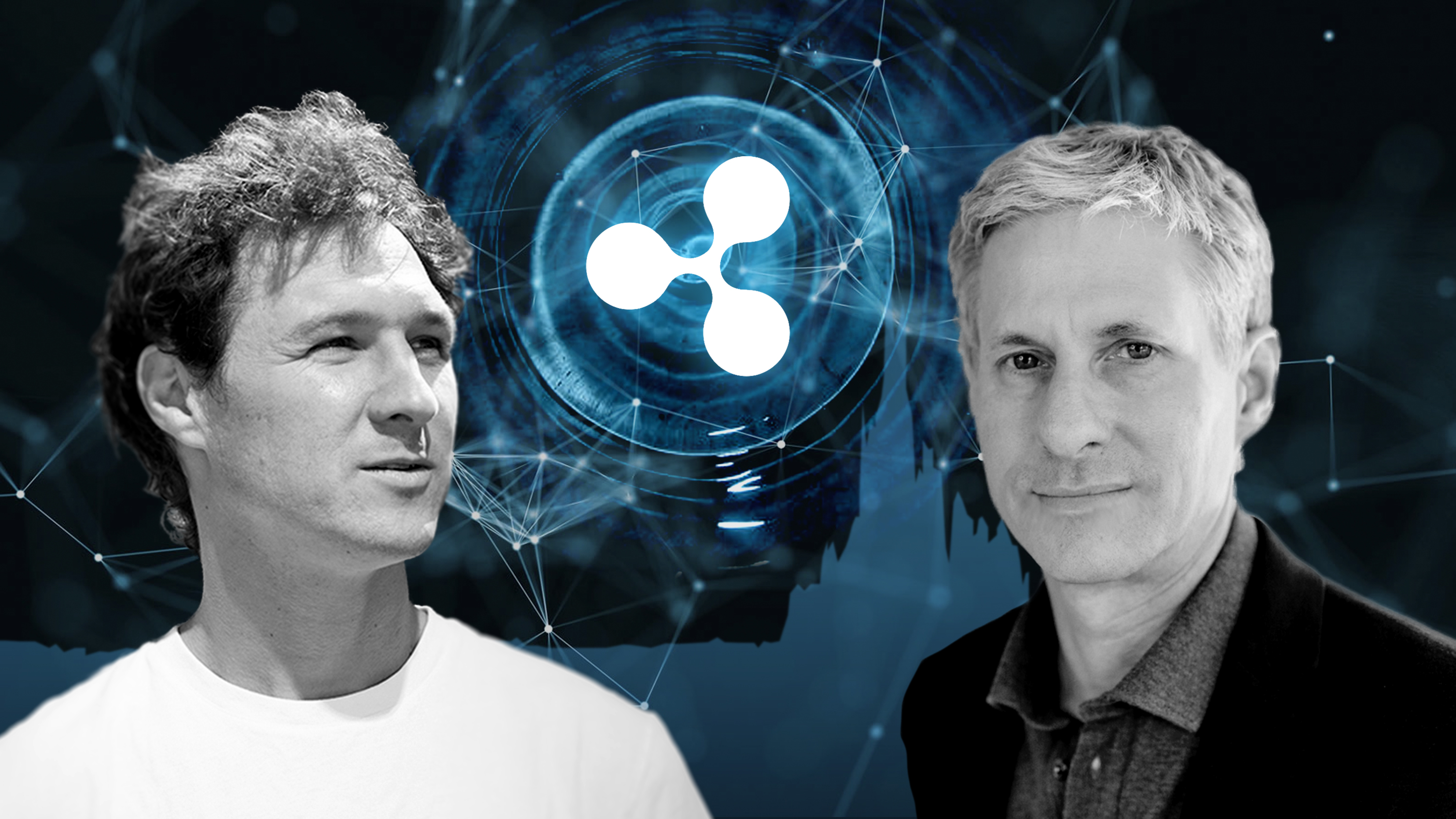

In this example, the person on the far right side of the lineup makes a payment of $20 to the person on the far left. Although the payer and recipient do not directly trust each other, the payment transfers through a chain of IOUs forged of seven people who are linked by six trusted relationships. (Source: Ripple.com)

The network architecture is not dissimilar to the idea behind the Lightning Network, except with counterparty risk, something which Lightning avoids. In our view, this model is likely to be unstable and the trust networks are unlikely to be regarded as reliable — and therefore we are unsure of its efficacy. Either the system would centralise towards a few large banks and fail to be sufficiently different to the existing financial system or it would be liable to regular defaults. However, the current Ripple system is very different to this original idea.

At the start of 2011, Bitcoin was gaining some significant traction and began to capture the attention of Ripple’s target demographic. To some extent, Bitcoin had succeeded where Ripple had failed, building a peer-to-peer payment network with what appeared to be a superior architecture to Ripple. In May 2011, Jed McCaleb, an early Bitcoin pioneer, joined Ripple, perhaps to address some of these concerns.

McCaleb had founded the Mt. Gox Bitcoin exchange in 2010, which he sold to Mark Karpeles in March 2011. According to an analysis of the failure of Mt. Gox by WizSec’s Kim Nilsson, the platform was already insolvent, to the tune of 80,000 BTC and $50,000, in March 2011 when McCaleb sold it. Shortly after this, Ryan Fugger handed the reins of the Ripple project to McCaleb.

This video from June 2011 describes some of the philosophy and architecture of Ripple after McCaleb had joined the project:

OpenCoin: September 2012 to September 2014

The Ripple logo during the OpenCoin period. (Source: Ripple.com)

In 2012, McCaleb hired Chris Larsen, who remains on the board today as the executive chairman and whom the current website describes as a co-founder of Ripple. This marked the start of the OpenCoin era, the first of three name changes between 2012 and 2015. Larsen is the former chairman and CEO of E-Loan, a company he co-founded in 1996, took public in 1999 at the height of the tech bubble, and then sold to Banco Popular in 2005. Larsen then founded Prosper Marketplace, a peer-to-peer lending platform, which he left to join Ripple in 2012.

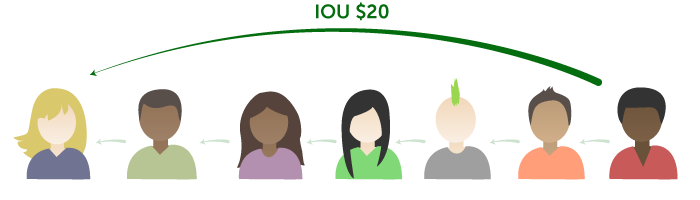

Larsen is not new to volatile prices and price bubbles. E-Loan experienced a peak-to-trough fall of 99.1% between 1999 and 2001. E-Loan’s IPO share price stood at $14 on 28 June 1999 before selling for $4.25 per share in 2005. (Source: Bloomberg)

To address the success of Bitcoin, Ripple now planned to allow Bitcoin payments on its network, potentially as a base currency for settlement. This period also marked the launch of the Ripple Gateway structure. The community realized that the peer-to-peer structure did not seem to work, with ordinary users unwilling to trust counterparties sufficiently to make the network usable for payments. To address this, Ripple decided to form gateways, large businesses that many users would be able to trust. This was said to be a compromise, a hybrid system between traditional banking and a peer-to-peer network.

How Ripple gateways work. (Source: Ripple.com)

In late 2012, OpenCoin opposed the usage of the name “Ripple Card” by Ripple Communications, a telecom company that predated the launch of the Ripple payment network. This may illustrate the start of a change in culture of the company, with a willingness to use the law to protect the company, and a change in strategy to focus more on the Ripple brand.

Ripple Communications is an unrelated telecom company based in Nevada that held the Ripple.com domain and used the Ripple name before the Ripple payment network came into being. (Source: Internet Archive)

In October 2012, Jesse Powell, the founder and CEO of the Kraken exchange (which launched in 2011) and close friend of McCaleb, participated in Ripple’s first seed round with an investment believed to total around $200,000. Roger Ver is also said to have been an early investor in Ripple, apparently investing “before even the creators knew what it was going to be”.

XRP token launch: January 2013

Ripple released its XRP coin in January 2013. Like Bitcoin, XRP is based on a public chain of cryptographic signatures, and therefore did not require the initial web of trust or gateway design. XRP could be sent directly from user to user, without the gateways or counterparty risk, which was the method used for all currencies on Ripple, including USD. Ripple perhaps intended XRP to be used in conjunction with the web of trust structure for USD payments — for example, to pay transaction fees. The company set the supply of XRP at a high level of 100 billion, with some claiming this would help Ripple prevent sharp price appreciation. Critics argued that the XRP token may not have been a necessary component of the network.

In April 2013, OpenCoin received $1.5 million in funding from Google Ventures, Andreessen Horowitz, IDG Capital Partners, FF Angel, Lightspeed Venture Partners, the Bitcoin Opportunity Fund, and Vast Ventures. This was the first in many rounds of venture funding and it included some of the most respected venture-capital companies in the world.

McCaleb left the project sometime between June 2013 and May 2014. Although his departure appears to have only been widely discussed within the Ripple community starting in May 2014, later statements from the company indicates he ended his involvement in June 2013 when Stefan Thomas took over as CTO. Thomas had created the We Use Coins website in March 2011 and the 2011 “What is Bitcoin?” YouTube video.

McCaleb appears to have disagreed with Larsen on strategy and then was seemingly forced out of the project, based on support Larsen received from the new venture-capital investors. After leaving Ripple, McCaleb went on to found Stellar in 2014, a project said to be based on some of the original principles behind Ripple.

Ripple Labs: September 2013 to October 2015

In September 2013, OpenCoin became Ripple Labs.

In February 2014, Ripple implemented the “balance freeze” feature, which it activated in August 2014. This allowed Ripple gateways to freeze or even confiscate coins from any user of its gateway, even without a valid signature for the transaction. The motivation of this was said to be to enable gateways to comply with regulatory requirements, for example, a court order demanding the confiscation of funds. The default setting for a gateway was to have the freeze feature enabled, but it was possible for a gateway to disable this option by using a “NoFreeze” flag, such that tokens a gateway owed could not be frozen or confiscated using this feature. The largest gateway at the time, Bitstamp, did not opt out of the freeze feature.

In May 2015, regulatory authorities in the United States fined Ripple Labs $700,000 for violating the Bank Secrecy Act by selling XRP without obtaining the required authorisation. Ripple additionally agreed to remedial measures, the most onerous of which are summarised below:

- Ripple Labs must register with FinCEN.

- If Ripple gives away any more XRP, those recipients must register their account information and provide identification details to Ripple.

- Ripple must comply with AML regulations and appoint a compliance officer.

- Ripple must be subject to an external audit.

- Ripple must provide data or tools to the regulators that allows them to analyse Ripple transactions and the flow of funds.

Ripple: October 2015 to present

In October 2015, the company simplified its name to Ripple.

The current Ripple logo. (Source: Ripple.com)

In September 2016, Ripple raised $55 million in funding in a round lead by Japan’s leading online retail stock-brokering company, SBI Holdings (8473 JP). SBI acquired a 10.5% stake in Ripple. As we mentioned in our “Public companies with exposure to the crypto space” piece, this is part of a wide range of SBI investments into crypto. SBI and Ripple have set up a joint venture, SBI Ripple Asia, which is 60% owned by SBI and 40% owned by Ripple. The company is hoping to provide a settlement platform using Ripple’s “distributed financial technology”.

In September 2017, R3, another blockchain company, sued Ripple. R3 argued that Ripple agreed in September 2016 to give it the option to buy 5 billion XRP at an exercise price of $0.0085 before September 2019. At the peak, the intrinsic value of this call option was worth around $16.5 billion. R3 alleges that in June 2017, Ripple terminated the contract, despite having no right to do so. Ripple then filed a counter case, alleging that R3 did not honour its side of the original 2016 agreement by failing to introduce Ripple to a large number of banking clients or to promote XRP for usage in these banking systems. As of February 2018, the case is unresolved.

Ripple supply and company reserves

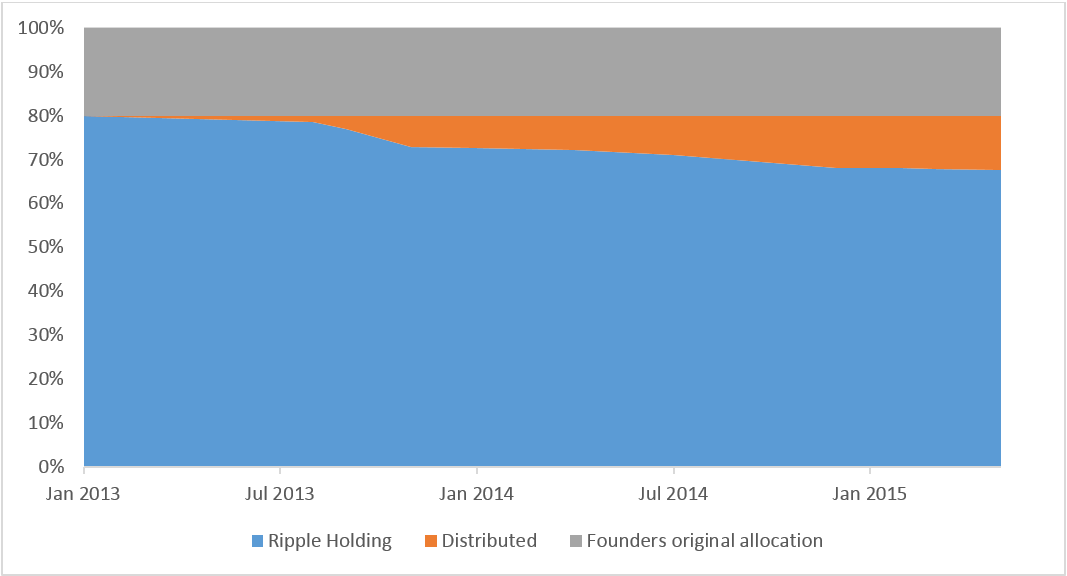

When Ripple was founded, it created 100 billion XRP tokens of which 80 billion tokens were allocated to the company and 20 billion were given to the three founders. Here is an approximate breakdown of the distribution of those tokens:

- The Ripple company received 80 billion XRP.

- Chris Larsen received 9.5 billion.

- In 2014, Larsen committed to put 7 billion XRP of this 9.0 billion into a charitable foundation.

- Jed McCaleb received 9.5 billion. Upon leaving Ripple:

- McCaleb retained 6.0 billion (subject to lock up agreement).

- McCaleb’s children received 2.0 billion (subject to lock up agreement).

- 1.5 billion was given to charity and other family members of McCaleb (not subject to lock up agreement).

- Arthur Britto received 1.0 billion (subject to lock up agreement).

When McCaleb left Ripple, there were concerns he was, could or would dump his XRP into the market and crash the price. McCaleb and Ripple constructed the following agreement to prevent this by restricting the sale of XRP. The agreement was revised in 2016 after Ripple accused McCaleb of violating the initial terms.

| 2014 agreement |

|

(Source: http://archive.is/cuEoz)

As for the 80 billion XRP held by the Ripple company, the plan was to sell or give away this balance, use the funds to fund company operations, and to use it to seed global money-transfer gateways. As the Ripple wiki says:

XRP cannot be debased. When the Ripple network was created, 100 billion XRP was created. The founders gave 80 billion XRP to the Ripple Labs. Ripple Labs will develop the Ripple software, promote the Ripple payment system, give away XRP, and sell XRP.

From December 2014 to July 2015, the company disclosed on its website the amount of XRP it held, the amount in circulation, and indirectly (by mentioning a reserve) the amount spent on company operations. The company did not distinguish between what it sold and what it gave away for free. The disclosure for 30 June 2015 is shown below.

(Source: Ripple.com)

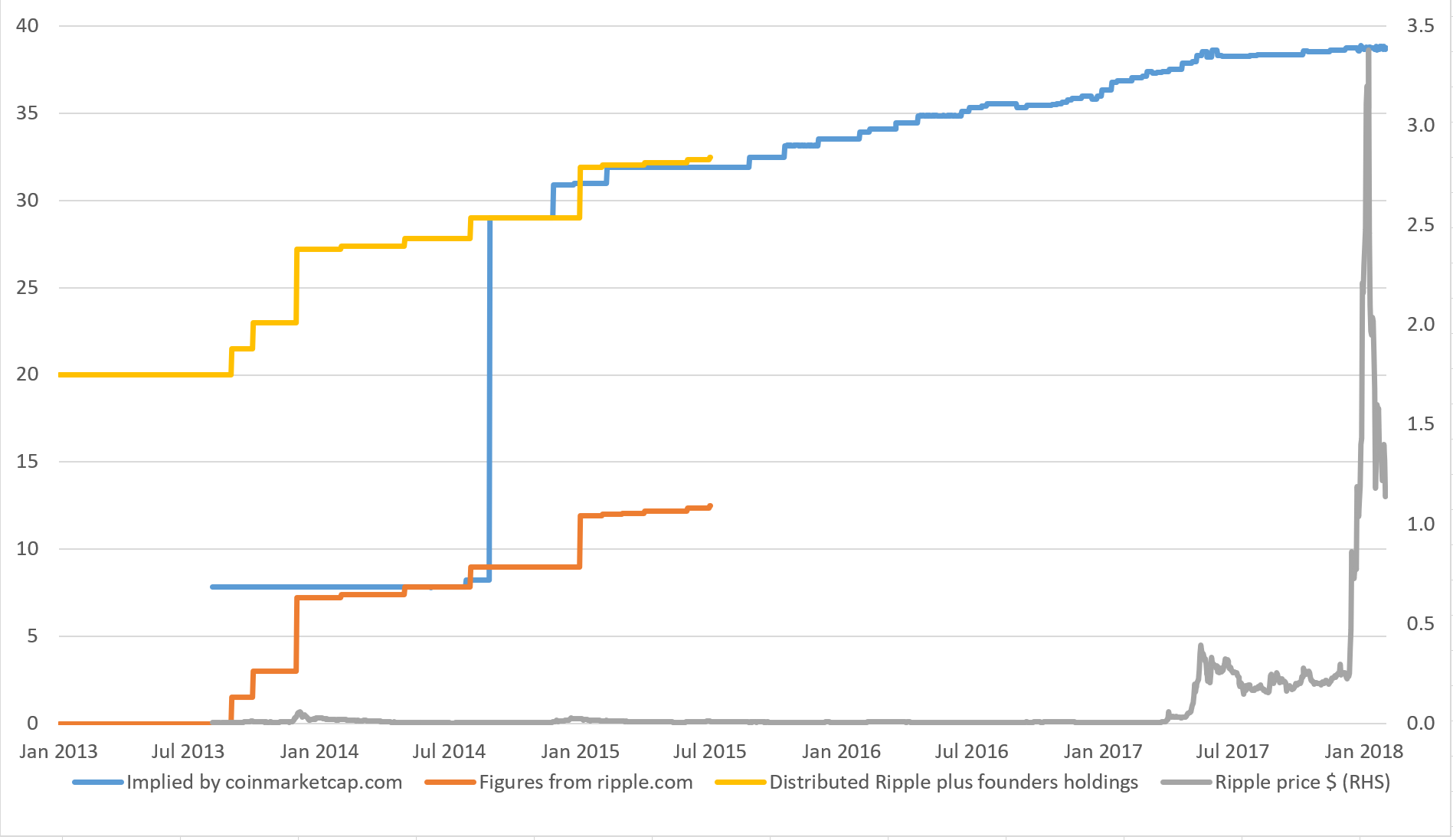

Some time after July 2015 the disclosure was modified, with the reserve balance no longer available. Since at least late 2017 Ripple disclosed three figures, the “XRP held by Ripple”, “XRP distributed” and “XRP to be placed in escrow”. As at 31 January 2018, the balances are as follows:

- 7.0 billion XRP held by Ripple

- 39.0 billion XRP distributed

- 55.0 billion XRP placed in escrow

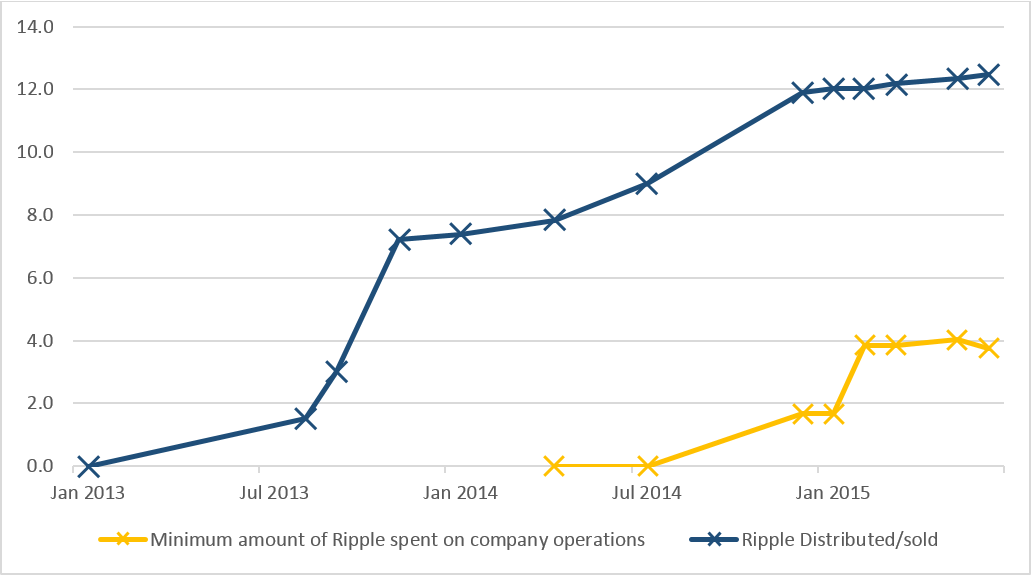

We have been unable to link or reconcile the old Ripple reserve figure with the new XRP held by Ripple figure, therefore we are unsure how much the company has spent on its own operations across the entire period. However, we have analysed the information disclosed in the old way prior to July 2015, 12 data points in total, in addition to forum posts from the company’s current chief cryptographer David Schwartz (regarded as one of the main architects of Ripple’s technology, who goes by the name JoelKatz online and is said to have had 1 billion XRP). The following charts present our findings related to the distribution or spend of XRP.

XRP holdings from 2013 to 2015 – billion. (Source: BitMEX Research, Ripple.com)

XRP distribution (sales to partners plus XRP given away) and XRP spent on company operations – billions. The crosses represent points where information was available. We are not aware of why the amount spent on company operations appears to decline towards the end of 2015. (Sources: Ripple.com, https://forum.ripple.com/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=3645, https://forum.ripple.com/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=3590)

XRP in circulation – billions. (Source: Ripple.com, https://forum.ripple.com/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=3645, https://forum.ripple.com/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=3590, Coinmarketcap/new Ripple disclosure)

The data shows that Ripple sold or distributed 12.5 billion XRP from January 2013 to July 2015. We have been unable to determine how many XRP were sold, at what price, or how many were given away. The company spent at least 4 billion XRP on company operations between March 2014 and July 2015 but there are no details of what this was spent on, as far as we can tell.

Dispute between company founders

As we alluded above, McCaleb did not part with the company on the best of terms. In May 2014, early Ripple investor Jesse Powell described the situation:

Since Jed’s departure, the management of the company has taken a different direction. Sadly, the vision Jed and I had for the project in the early days has been lost. I’m no longer confident in the management nor the company’s ability to recover from the founders’ perplexing allocation to themselves of 20% of the XRP, which I had hoped until recently would be returned. Prior to Jed’s departure from Ripple, I had asked the founders to return their XRP to the company. Jed agreed but Chris [Larsen] declined — leaving a stalemate. This afternoon, I revisited the allocation discussion with the pair and again, where Jed was open, Chris was hostile.

Ripple responded to Powell with a claim that he was spreading false and defamatory information in violation of his obligations as a Ripple board member. The letter states:

In fact, as Chris has stated previously in discussions with you and Jed, he has been and remains willing to return most of his founders’ XRP to Ripple Labs.

Powell retorted that Larsen would return only a portion of his XRP to the company, and rather than giving it back, this would be a loan. Powell ends the letter by explaining how he sees the situation with respect to the 20 billion XRP granted to the founders and the formation of Ripple:

Jed and I got started with Ripple in September of 2011. I believe Chris joined sometime around August of 2012. Prior to Chris joining, the company had two investors. I’m not sure when Jed and Chris allocated themselves the XRP but they say it was before incorporation, which occurred in September of 2012. In my view, the two stole company assets when they took the XRP without approval of the early investors, and without sharing the allocation amongst the other shareholders. Whatever coin they allocated themselves prior to incorporation of Opencoin, I believe was abandoned. There had been several ledger resets between Sep 2012 and Dec 2012, and a new version of Ripple emerged, built by Opencoin, clearly with company resources. If Jed and Chris have continued to run the old software to preserve their Betacoin, I have no problem. Unfortunately, Jed and Chris again allocated themselves XRP in December of 2012. That XRP unquestionably was not gifted by Jed and Chris to the company, it did not exist prior to the company’s existence, and it was generated with company resources. That XRP has always belonged to the company and it was taken from the company by Jed and Chris. I’m asking them to return what they’ve stolen.

Powell continued to comment on the situation on the Ripple forum:

The board and investors have known about it for a long time. I’d been nudging them to return the XRP since I found out about it. Jed was always willing but Chris wasn’t, and Jed kept his share in case leverage was ever needed to more aggressively persuade Chris to return his portion. It wasn’t a regular topic of discussion and was just something I just imagined would work itself out when Chris got a grasp on the damage it was doing to Ripple’s image and adoption. If my goal had been to get my fair share, I probably would have been more proactive about it but I’d just assumed it would eventually be entirely returned to the company. I could have agreed to a small amount of XRP being paid out in lieu of cash compensation or instead of equity, but otherwise, we all should have bought our XRP at the market rate, like everyone else.

The company, through marketing VP Monica Long, then responded to the Powell’s continued public pressure with the following commitment:

Further, co-founder and CEO Chris Larsen has authorized the creation of a foundation to distribute his donation of 7 billion XRP to the underbanked and financially underserved. This plan has previously been in development but is now being accelerated and finalized independent of a formal agreement amongst all the original founders. He believes this is both the right thing to do and the best way to remove further distractions in pursuit of the broader vision of the company. Details of the foundation, its independent directors, and the giveaway will be forthcoming.

The above response appeared to divert the pressure on Ripple and Larsen that was building inside the Ripple community. The foundation that was set up is Ripple Works. We have reviewed the charity’s US tax filings for the fiscal years ended April 2015 and April 2016, which show the following donations of XRP:

| Date | Donor | Amount (XRP) |

| November 2014 | Chris Larsen | 200 million |

| April 2015 | Chris Larsen | 500 million |

| July 2015 | Chris Larsen | 500 million |

| November 2016 | Ripple Inc | 1,000 million |

As of April 2016, two years after the commitment, Larsen appears to have given at least 1.2 billion XRP out of the promised 7 billion XRP total to the foundation. We have not been able to obtain the filling for the year ended April 2017, as it may not be available yet.

The dispute and the Bitstamp Ripple freeze incident

In 2015, Ripple took advantage of the Ripple freeze feature instituted in August 2014. The Bitstamp gateway froze funds belonging to a family member of Jed McCaleb. Some consider this ironic: Ripple originally stated that the freeze feature was implemented to enable gateways to comply with orders from law enforcement yet the first actual usage of the feature appears to have been an order to comply with an instruction from the Ripple company itself, against one of the founders.

What appears to have happened is a family member of McCaleb sold 96 million XRP (perhaps part of the 2 billion XRP given to other family members and not part of the lock-up agreement) back to Ripple for around $1 million. After Ripple acquired the XRP for USD, Ripple appears to have asked Bitstamp to use the Ripple freeze feature to confiscate the $1 million Ripple had just used to buy the tokens. In 2015, Bitstamp took both Ripple and McCaleb to court, to determine the best course of action.

Court documents allege/reveal the following:

- McCaleb had 5.5 billion XRP.

- McCaleb’s two children held 2 billion XRP.

- Another 1.5 billion XRP were held by charitable organizations and other family members.

- In March 2015, Jacob Stephenson, a relative of McCaleb, offered to sell 96 million XRP to Ripple.

- Ripple agreed to pay nearly $1 million to buy the 96 million XRP from Stephenson in a complicated transaction that “manipulated the market” to “improperly inflate the price per XRP of the transaction and mislead other purchasers”. As part of this, Ripple paid more than the cost and asked Stephenson to return an excess amount of $75,000.

- Bitstamp’s chief legal officer was also an advisor to Ripple and as such there was a conflict of interest.

The dispute between McCaleb and Ripple continued until a final resolution in February 2016, when the company, implying that McCaleb had violated the 2014 XRP lock-up agreement, stated that a final settlement had been reached:

Jed exited Ripple back when it was OpenCoin in June 2013. He has played no role in the strategy or operations of Ripple since then. He has, however, held significant stakes of XRP and company shares. In August 2014, we shared the terms of a lock-up agreement that dictated timetables and limits within which Jed could sell XRP. The purpose of the agreement was to ensure distribution of his XRP in a way that would be constructive for the Ripple ecosystem. Since April 2015, Jed has been party to ongoing legal action related to alleged violation of the 2014 agreement.

McCaleb responded to this with his side of the story, indicating that he was also happy with the final agreement.

This week also sees the end of a longstanding issue. Stellar and I have finally reached a settlement with Ripple in the ongoing dispute between the parties. The settlement shows that Ripple’s claims were entirely baseless. Ripple has conceded in exchange for Stellar and I agreeing to settle the litigation.

Under the final agreement, McCaleb’s family member’s $1 million were unfrozen, Ripple agreed to pay all legal fees, and 2 billion XRP were freed for donation to charity. McCaleb would be free to sell his remaining XRP, perhaps over 5 billion XRP, consistent with the terms in the table below.

| 2014 agreement | 2016 revised agreement |

|

|

(Source: http://archive.is/cuEoz)

The Ripple consensus process

The consensus system

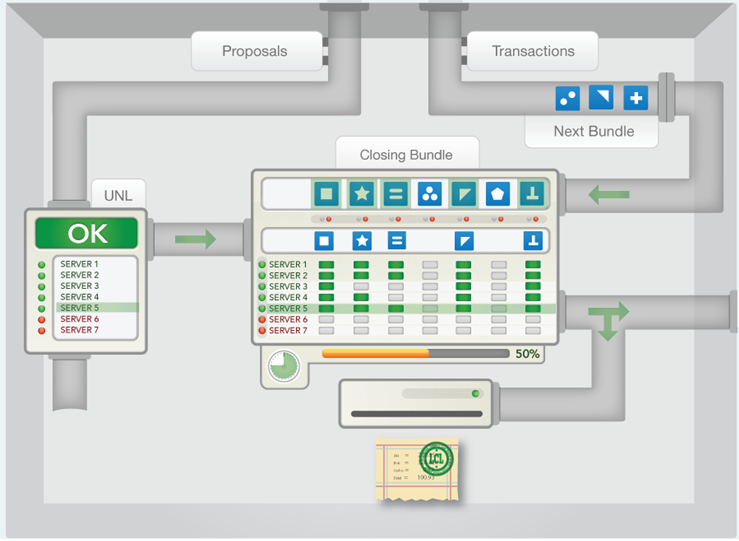

The Ripple technology appears to have gone through several iterations, but a core part of the marketing of Ripple is the consensus process. In 2014, Ripple used the image below to illustrate the consensus system, which seems to be an iterative process with servers making proposals and nodes only accepting these proposals if certain quorum conditions are met. An 80% threshold of the servers is considered a key level and once this threshold is crossed, a node regards the proposal as final. The image depicts some complexity in the process and the BitMEX Research team is unable to understand the detailed inner workings of the system or how it has any of the convergent properties necessary for consensus systems.

(Source: Ripple wiki)

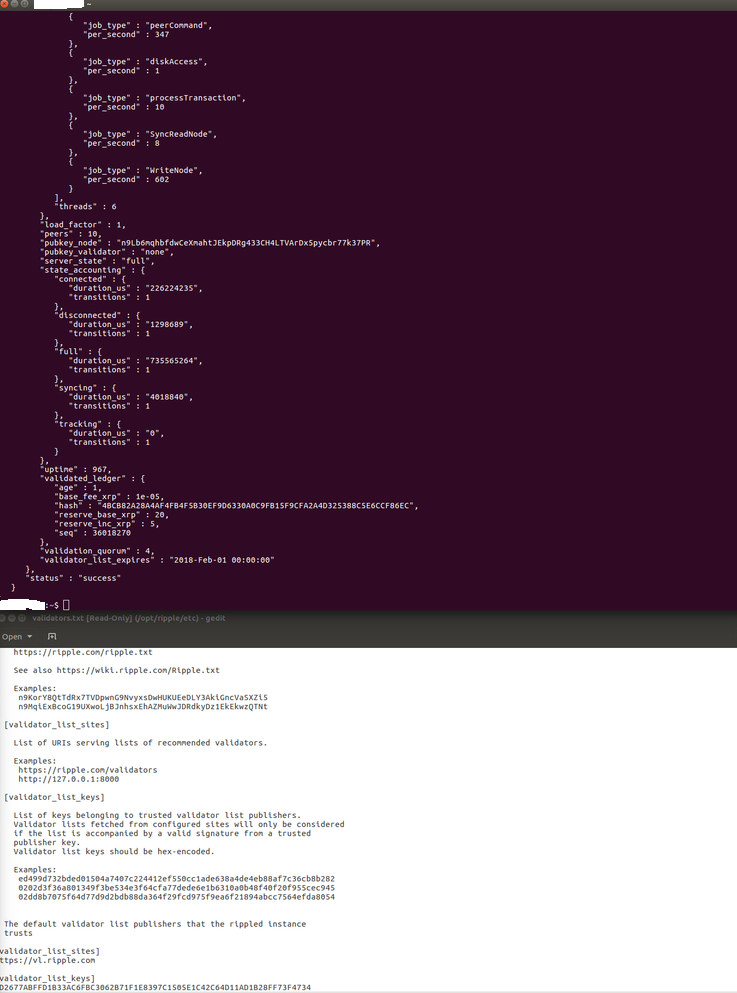

In January 2018, the BitMEX Research team installed and ran a copy of Rippled for the purpose of this report. The node operated by downloading a list of five public keys from the server v1.ripple.com, as the screenshot below shows. All five keys are assigned to Ripple.com. The software indicates that four of the five keys are required to support a proposal in order for it to be accepted. Since the keys were all downloaded from the Ripple.com server, Ripple is essentially in complete control of moving the ledger forward, so one could say that the system is centralised. Indeed, our node indicates that the keys expire on 1 February 2018 (just a few days after the screenshot), implying the software will need to visit Ripple.com’s server again to download a new set of keys.

A screenshot of Rippled in operation. (Source: BitMEX Research)

Of course, there is nothing wrong with centralised systems; the overwhelming majority of electronic systems are centralised. Centralisation makes systems easier to construct, more efficient, faster, cheaper to run, more effective at stopping double spends and easier to integrate into other systems. However, some Ripple marketing, like the image below, contends that the Ripple system is distributed, which some may consider misleading.

(Source: Ripple.com)

In addition to the potentially misleading marketing, the construction involving the quorum process and 80% threshold may not be necessary and merely adds to the obfuscation, in our view. Defenders of Ripple could argue that the list of five public keys is customizable, as one could manually edit the configuration file and type in whatever keys one wants. Indeed, there is a list of such validators on the Ripple website. However, there is no evidence that many users of Ripple manually change this configuration file.

Even if users were to modify the configuration file, this may not significantly help. In this circumstance, there is no particular reason to assume that the system would converge on one ledger. For example, one user could connect to five validators and another user could connect to five different validators, with each node meeting the 80% thresholds, but for two conflicting ledgers. The 80% quorum threshold from a group of servers has no convergent or consensus properties, as far as we can tell. Therefore, we consider this consensus process as potentially unnecessary.

Validation of the ledger

Although the consensus process is centralised, one could argue that in Ripple user nodes can still validate transaction data from all participants. This model can be said to provide some assurance or utility, despite its computational inefficiency. Although moving the ledger forward is a centralised process, if the Ripple servers process an invalid transaction, user nodes may reject those blocks and the entire network would then be stuck. This threat could keep the Ripple server honest. However, this threat may not be all that different from the existing user pressure and legal structures which keep traditional banks honest.

Apparently, Ripple is missing 32,570 blocks from the start of the ledger and nodes are not able to obtain this data. This means that one may be unable to audit the whole chain and the full path of Ripple’s original 100 billion XRP since launch. This could be of concern to some, especially given Powell’s comments, which indicate that there may have been resets of the ledger in the early period. David Schwartz explained the significance of the missing blocks:

It doesn’t mean anything for the average Ripple user. In January of 2013, a bug in the Ripple server caused ledger headers to be lost. All data from all running Ripple servers was collected, but it was insufficient to construct the ledgers. The raw transactions still survive, mixed with other transactions and with no information about which transaction went in which ledger. Without the ledger headers, there’s no easy way to reconstruct the ledgers. You need to know the hash of ledger N-1 to build ledger N, which complicates things.

Conclusion

Much of this report has focused on disputes, primarily related to control over XRP, including accusations of theft. Perhaps such disputes are not particularly unique, especially given the rapid, unexpected growth in the value of the ecosystem. In fact, this story of the disputes might not be too dissimilar from that of some of the large tech giants mentioned in the introduction to this piece.

More significant than the disputes is the fact that the Ripple system appears for all practical purposes to be centralised and is therefore perhaps devoid of any interesting technical characteristics, such as censorship resistance, which coins like Bitcoin may have — although this does not mean that Ripple or XRP is doomed to failure. The company has significant financial capital and has proven somewhat effective at marketing and forming business partnerships, and perhaps this could mean the company succeeds at building adoption of the XRP token either among businesses or consumers. If so, the points that Bitcoin critics often raise may be even more pertinent and relevant in the case of XRP. These points include:

- The lack of inflation is a naive economic policy.

- The price of the token is too volatile and speculative.

- Regulators will shut the system down if it becomes popular.

- Perhaps most importantly, why not use the US dollar? Banks will build competing digital systems based on traditional currencies (if they don’t exist already).

The real mystery about Ripple is that, given the large market value of the system, why are all the Bitcoin critics so silent? Perhaps the answer to this question is just as applicable to some of Bitcoin’s proponents as it is to its critics. Most people seem to judge things based on what they perceive as the culture and character of those involved, rather than on the technical fundamentals.

Disclaimer

Whilst many claims made in this note are cited, we do not guarantee accuracy. We welcome corrections.