Abstract: Official inflation numbers have declined towards the 2% target and remarkably, interest rates have moved to historically more “normal” levels, above 5%. However, we predicted for years that returning to “normal” rates was impossible, we argued that the economy had rewired and was now addicted to near zero rates. Yet things seem fine now, so were we wrong this whole time? We stubbornly stick to our initial view, it’s just that there is a lag before the monetary tightening bites, a longer lag that we expected. The impact of the tightening will hit hard at some point.

Overview

During the middle of 2021, in the aftermath of the COVID-19 related stimulus, official inflation metrics started to pick up. While initially the authorities complacently dismissed this as “transitory”, after inflation picked up again, to higher levels, at the start of 2022, central banks finally reacted. Starting in March 2022, the Federal Reserve in the United States began to increase interest rates, from 0.25% to 5.5%, in eleven consecutive hikes. A monumental rally in rates. The inflation rate in the US has now declined, from a peak of 9.1% in June 2022 to just 3.0% by June 2023. Inflation is now at a more moderate level and incredibly, interest rates are now also at a historically “normal” level too. In most of the 1990s and in the run up to the 2008 global financial crisis, rates were also around 5.0% to 5.5%. Therefore rates can now be considered as “back to normal”.

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2008, as a response, interest rates fell to near zero in most western countries and stayed pretty much at this level for the next 14 years. This policy was controversial and was vehemently criticised by many, including ourselves. Criticisms of the near zero rates included the following:

- Such rates are historically unprecedented, it is therefore an extreme monterey experiment and the outcome is highly uncertain.

- As rates were set too low for too long, the economy became addicted. Eventually inflation will emerge and when central banks attempt to withdraw the low rates, it will become extremely painful, akin to a drug addict going cold turkey.

- Lowering interest rates was merely a mechanism to kick the can down the road, rather than tackling the economic problems head on.

- The amount of debt expanded too fast to unsustainable levels, as too much consumption and investment was brought forwards.

- Vast sections of the economy have become rewired for lower rates and business models now exist that are only viable in low interest rate environments.

- Increasing interest rates back to normal levels, of say 5% is impossible. Central banks could raise rates to around 3%, however debt levels are too high and this would cause a collapse in financial markets and deleveraging.

- Unfortunately we are now locked into record low interest rates and increased financial repression. We are stuck with low rates forever.

Were we wrong for 14 years?

In the first half of 2023, central banks did manage to raise interest rates above 5% and yet the financial world did not blow up. This is not at all what we predicted. As at 22 September 2023, the S&P 500 Index is up 15.0% YTD and the NASDAQ Composite Index is up 28.7% YTD. Real GDP growth in the first half of 2023 is moderate, at just above 2% and the labour market also looks ok, with a reported unemployment rate of below 4%. The data illustrates that we may have been wrong for nearly 14 years.

United States banking crisis of 2023

There was of course a banking crisis in the United States at the start of 2023, resulting in the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, Silvergate Bank and First Republic Bank. And it is true to say the cause of this crisis was the complacency driven by years of low interest rates, followed by the aggressive rate increases in 2023. The unintended consequences of “Operation Chokepoint 2.0”, a cynical campaign by some US regulatory bodies against the cryptocurrency industry, may have been a contributing factor or catalyst, however we do not believe it was really the fundamental cause of this crisis. Although some people in cryptocurrency circles like to blame Operation Chokepoint 2.0, as it’s a nice story, we think it was interest rates that did it.

Nevertheless, the 2023 banking crisis now appears resolved. In any event, the magnitude of this crisis was minimal. If after over a decade of biblically loose monetary policy and excesses, the only real negative consequence when it all unwinds is a few scary bank failures, lasting a couple of months, then we can hardly say “I told you so”.

Lagged impact of higher rates

Despite the above evidence, we still stubbornly hold on to our view, that the 14 years of near zero interest rates were inappropriate and that we are still heading into a period of economic pain. We have modified our view slightly, we now believe there will be a significant lag between when the central banks increase rates and when much of the negative impact is felt. This length of this lag is greater than we anticipated and we never expected rates to get this high without more cracks emerging in the system.

Of course we could be wrong. After all, along with many others, we are biased. It is difficult to admit when one is wrong.

Conventional Wisdom

Conventional wisdom among commentators and market participants today is that the higher interest rates are working. Inflationary pressure is declining considerably. The fashionable view is that the economy will have a so-called “soft landing”. Weakening a bit, but in a slow and controlled manner. After this, with inflation returning towards the target, central banks can begin to lower interest rates again and the rally in equities and other assets can continue.

We oppose this conventional view. The lagged impact of the unprecedented monetary tightening since 2022 has not yet been felt to the extent that it will be. Over the coming months and quarters, cracks are likely to emerge and the economy will weaken in a way that looks uncontrolled. Equities and asset prices are likely to be weak in this environment and then after that, the monetary tightening could reverse in an emergency type manner, not the “soft landing” and then gradual loosening which the economic establishment would hope for.

Why have higher rates not bitten yet?

The primary reason the higher rates have not bitten hard yet may be psychological. Many financial market participants today, anyone born after around 1986, have experienced low interest rates for their whole careers. They may find it hard to adjust to and accept higher rates. It simply hasn’t sunk in yet and they subconsciously assume low rates will return and everything will be back to normal. Individuals and corporates may therefore have taken advantage of the good times, borrowing money and built up large gross cash positions. People are still spending the cash as the higher rates just haven’t sunk in yet.

Many individuals and corporates took advantage of the low rates and secureded long duration financing with low fixed rates. As time progresses and the cumulative impact of more and more refinancing occurs, the impact of the higher rates will start to bite.

New loan data

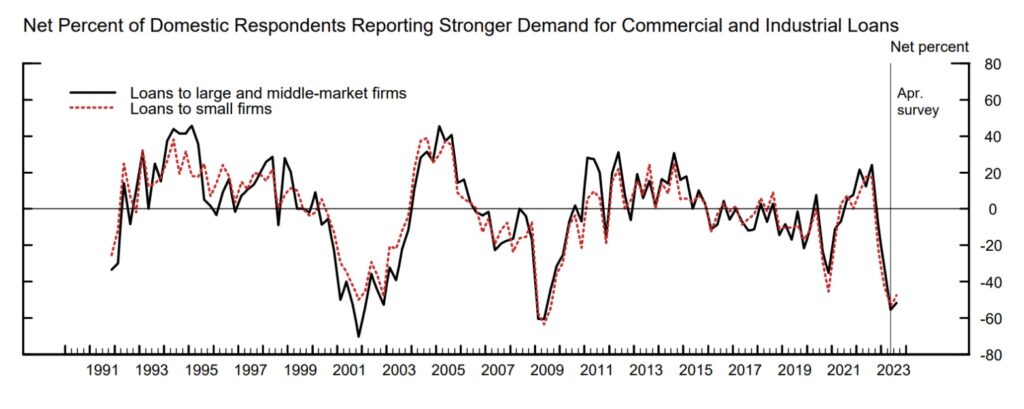

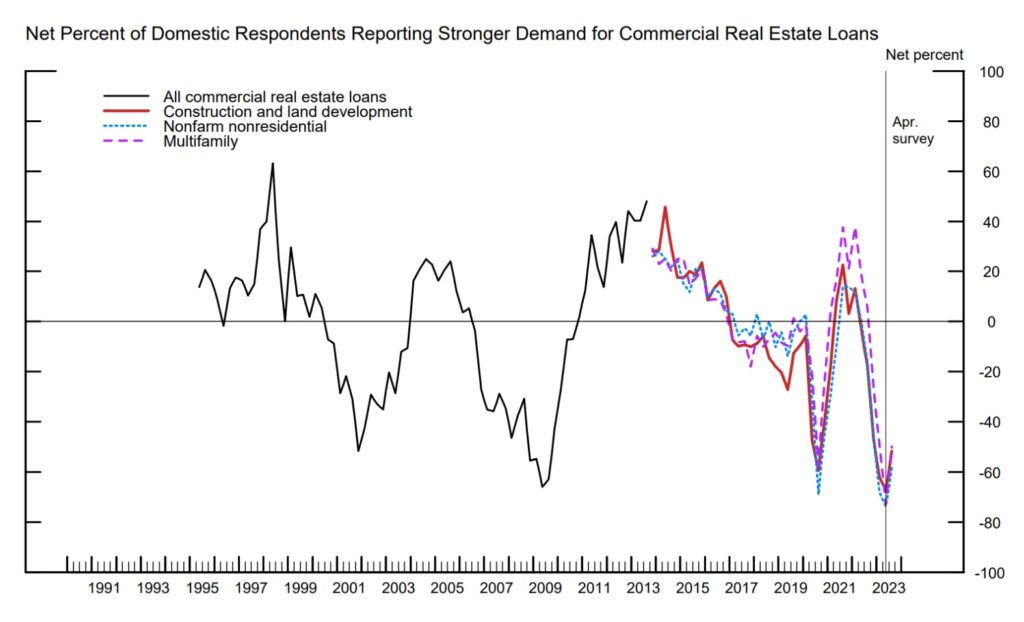

Corporates and consumers are also becoming increasingly reluctant to take on new loans at these higher rates, they are either waiting for rates to decline or spending with cash on hand. Therefore, while economic demand has remained reasonable, demand for new loans has fallen off a cliff. According to the July 2023 Federal Reserve Senior Loan Officer survey, as the chart below illustrates, demand for industrial and commercial loans is at its lowest level since the 2008 financial crisis. Demand for commercial real estate loans also matched the 2008 low, as the next chart shows.

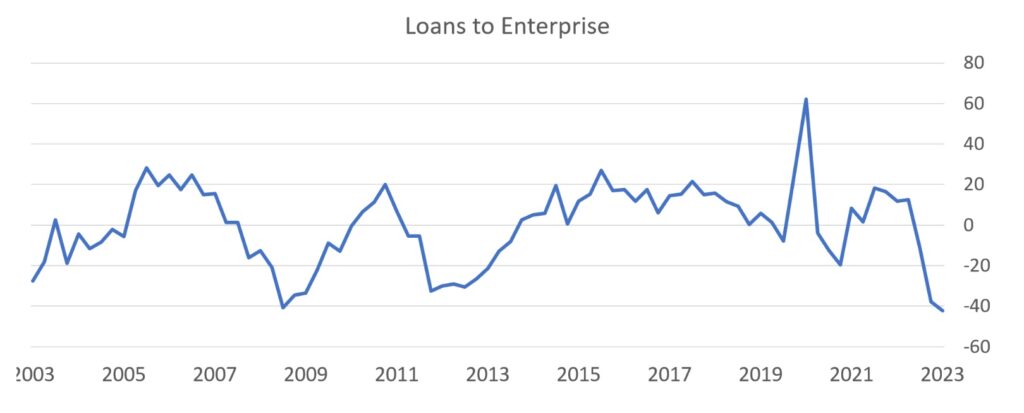

The July 2023 Euro area bank lending survey also paints a similar picture. Demand for business loans reached a record low in H1 2023, below 2008 levels, as the chart below illustrates.

An eventual credit contraction is therefore inevitable, in our view. The impact of higher rates on many areas of the economy have not been felt yet, as other actions short of taking out new loans are taken, to maintain spending and investment. But eventually the ability to do this will expire.

Financial conditions & money supply

We are already seeing a contraction in the money supply. M1 in the United States peaked at US$20.7 trillion in May 2022 and as at July 2023, the figure is US$18.5 trillion, a decline of 10.6%. Most of this decline has been driven by a flight of retail deposits into money market funds. However, M2, which includes retail money market funds, has also declined, falling by US$800 billion (3.9%) from its US$20.7 trillion July 2022 peak. This is the first decline in M2 since 1949, 74 years ago. This is so unprecedented that economists do not know how to interpret the decline or whether it will lead to slower economic growth.

This US$800 billion reduction in M2 is likely to be primarily driven by people withdrawing from banks to purchase government bonds to earn higher yields, rather than significant volumes of credit contraction. This US$800 billion M2 decline therefore approximately matches the US$800 billion contraction in the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet over the period. The Federal Reserve sells the US treasuries and the public purchases them with their bank deposits. This therefore doesn’t represent a decline in loans and all the data does is illustrate the manifestation of Federal Reserve policy of selling bonds. However, the declining M2 still represents a tightening in financial conditions and illustrates the scale of the tightening, which is of a magnitude not seen before.

The Eurozone has also experienced a sharp decline in M2, from a peak of EUR 15.5 trillion in September 2022, to EUR 15.1 trillion in June 2023, a decline of 2.6%. The first significant decline in the history of the monetary union.

Government Debt

An obvious area where the prevailing interest rates are unsustainable is government debt. The current United States government debt stands at US$32.3 trillion, while the US ten year treasury currently yields 4.5%. If all the debt is refinanced, with an average duration of 10 years, a basic calculation implies this represents an annual interest cost of around US$1.5 trillion. This is a huge amount of money, almost as much as the bloated United States military budget. The Congressional Budget Office recently projected that annual net interest costs would total US$663 billion in 2023 and more than double over the upcoming decade to US$1.4 trillion in 2033. Such high interest costs may be politically unsustainable and represent an obvious ticking economic time bomb.

Conclusion

The impact of the interest rate increases which have already occurred in 2022 and 2023, has not yet been felt in the economy or in equity markets to the extent which we believe it will. The magnitude of the monetary contraction is large and growing. However, the force of this tightening has so far been defanged. This is due to a combination of psychological factors, with many market participants unable to appreciate the scale of the tightening, as well has strong balance sheets, enabling many corporates and individuals to delay the impact of tighter conditions on their spending.

It is now a waiting game. Waiting for more and more of the loans to mature and the associated refinancing at higher rates. Waiting for the historically low level of demand for new loans to impact spending and cause credit contraction. The level of credit expansion and contraction is the primary driver of the economy and financial markets and if credit contracts, there will be no escape.

We do not know which area of the economy will be hit first or how the cracks will emerge, but it will be felt somewhere. And when this limit is reached, this is unlikely to result in a smooth “soft landing” and gradual reduction in interest rates to mitigate the problem. Given the magnitude of the level of debt involved and the extreme rate in the tightening of conditions, the limit is likely to be to hit hard and financial conditions will be volatile.

This post is part of our macro series of articles shown below: