(Any views expressed in the below are the personal views of the author and should not form the basis for making investment decisions, nor be construed as a recommendation or advice to engage in investment transactions.)

(Any views expressed in the below are the personal views of the author and should not form the basis for making investment decisions, nor be construed as a recommendation or advice to engage in investment transactions.)

Betwixt a placid pond and the high road rests an inn. That is where you shall find me, a humble inn keeper. Many interesting travellers traverse the road from here to hyperinflation. My lot is service to others. Fresh game, light ales, and good company is what I provide all stoppers-by. But do not be fooled by the sparse landscape – for there is immense power hidden here.

One strange evening, a samurai atop a gilded Kisouma (brandishing a Hattori Hanzo sword), a female knight striding on a Percheron, and a Yankee riding a bronco appeared on the road to hyperinflation. Taking refuge from their weary journey, these travellers alighted at my inn. I treated them to a hearty feast, and they washed down their meal with flagons of my finest ales. With their stomachs full and their cheeks warm, we gathered around the fire, and they regaled me with the tale of woe that drove them to band together and set them on their righteous path.

Feast your eyes upon my esteemed guests.

Haruhiko Kuroda – The Samurai, the Yahweh of the Yen.

Christine Lagarde – The Knight, and the Empress of the Euro.

Jerome Powell – The Yankee, and the Don of the Dollar.

When I learned the identities of the travellers, I sat aghast. How could a humble inn keeper such as myself share the same rarified air as these lords? Words and manners escaped me, and I asked point blank: “What hardships could have forged such an unlikely alliance?”

They shuddered, raised a collective eyebrow in surprise, and asked: “Surely, you’ve heard the tales of the Great Bear?”

In my defence, I informed them I did not possess the latest technology and was thus incapable of accessing the font of all culture and knowledge, TikTok.

“Well, there exists a Great Bear, and this Bear, once tamed, has recently broken free, raining terror on the land,” Sir Powell explained, his face twisted into a determined scowl. “It is our duty to do what we must to free ourselves from the yoke of this Bear.”

“The Bear and his subjects once provided many essential commodities to the citizens of the realm at agreeable prices. But then the Bear grew violent, taking up arms against one of our shared allies. It quickly became clear that this Bear needed to be taught a lesson– so we decided to stop purchasing the Bear’s goods.”

“Heavens!” I responded. “How noble of you and your subjects to suffer so that the world may be rid of this nasty Bear. Pardon my ignorance, Sir Powell, but pray tell– how did your boycott fare?”

Sir Powell shook his head, and before he could open his mouth, Kuroda-dono shouted, “It has been for naught! The bear has retaliated with this damned inflation, which is ravaging our kingdom.”

“Our kingdom, too, suffers under the oppressive thumb of inflation at the hand of this Bear,” Lady Lagarde added softly, head hung low in defeat. “What an evil, evil beast.”

Sir Powell stayed quiet, staring at the floor. I turned to him and inquired whether his kingdom had suffered the same misfortune.

“Yes, but my kingdom is blessed,” Sir Powell replied (muttering “God Bless America, and no one else,” under his breath). “The gods saw fit to bless my kingdom with sufficient food and energy to weather this storm. It is from this position of strength that we enlisted the help of our allies in our crusade against the Bear. The kingdoms of the Yen and the Euro are not so lucky, but we are here to support them.”

“And how will you support your allies, Sir Powell?” I asked.

“It will be difficult, but we possess the mightiest of powers. Look into my satchel and tell me what you see,” he said.

He held out his bag, and I peered inside. “I behold a…printer? A printer with green pieces of paper on its tray?” I was flummoxed. How could this unassuming device be the mighty weapon of which he spoke?

“Your eyes do not deceive you. This gift from the gods grants me alone the power to create the most magical of items – the Dollar. I shall print many of these Dollars, and with them, I can purchase the loyalty of my good friends,” Sir Powell declared proudly.

“Please, Sir Powell, we need these Dollars,” Lady Lagarde pleaded. She fell to her knees in supplication, the spitting image of a common beggar.

“I have done my duty, and I do own the government bonds of my kingdom in vast quantities, but it is not enough,” Kuroda-dono added glumly. “I alone cannot win this battle against inflation. My currency, the Yen, suffers greatly from the Yield Curve Control. I implore the good Sir Powell to print the Dollar and buy my bonds. Oh please, my lord!”

“I, too, need the righteous Sir Powell to purchase my Euro bonds,” said Lady Lagarde. “My kingdom is vast, and certain nobles are more prosperous than others. Some of the nobles are extremely profligate, I should add, but their cuisine is quite tasty. If I wish to keep my kingdom as one, I must provide near-boundless support for the less fortunate. I must print the Euro and purchase the loyalty of my subjects. But I cannot do it alone, for I also cannot fully control the value of my currency, the Euro. It gets weaker the more I provide to the wayward nobles. And I must buy more and more of the Bear’s goods, and they cost more the weaker the Euro becomes. But I am loyal to Sir Powell, and I have given my word that I shall not do business with the Bear. What am I to do? My subjects will soon get cold and hungry. Please, oh please, Sir Powell– help us.”

I turned to Sir Powell. “Are you such a righteous lord? Will you do what is asked of you?”

“Of course, innkeeper. It is the duty of my kingdom to support her allies,” he replied.

“But Sir Powell,” I continued. “I opened this antiquated technology called a book, and I read that your kingdom was engaged in an effort called The Quantitative Tightening. And in this book, the author suggested that you pledged to stop printing the Dollar so that the inflation inside your kingdom would subside.”

Sir Powell let out a loud guffaw. “Books! Who reads those anymore? I suggest you read the real news, which you can find in The Wall Street Journal – a newspaper penned by my sycophantic interlopers. You forget that I can quantitatively tighten and print the Dollar to purchase Yen and Euro bonds.”

“My kingdom is great, but even we suffer economic recessions from time to time,” Sir Powell continued. “By the powers vested in me, I shall create a recession by removing liquidity from the market, and then ride to the rescue with Dollars from my printing press.”

“Egads, Sir Powell– you are so powerful and wise!” I exclaimed. “I am ashamed that I have not been reading the right material. I shall correct this post-haste. I have just one last question for you – is there anything that cannot be solved by printing Dollars?”

“There is not a problem on this green earth that printed Dollars cannot fix, young lad,” Sir Powell boasted.

Seizing on this window of opportunity, Kuroda-dono and Lady Lagarde chimed in: “Well, Sir Powell, we’d like to see you prove it! We humbly request that you grow even more aggressive in your plot to create a recession in your kingdom, so that you may start cutting interest rates. We, the kingdoms of the Yen and the Euro, have deliberately kept our interest rates below inflation and engaged in the Yield Curve Control so that our banking and political systems may survive. Even though we care not about the suffering of the masses, the inflation we have endeavoured to create may break them – and our heads may follow. So please, Sir Powell, help us – our time is short.”

I was so honoured that such good and noble persons graced my inn. Read on, and remember this story well – for there is more to tell once you’ve learned about the Yield Curve Control and its effects on the Yen, Euro, and Dollar.

The Thesis

Japan and the European Union (EU) are both engaging in Yield Curve Control (YCC), either explicitly or implicitly. YCC is when a central bank engages in the price fixing – more commonly known as “manipulation” to us non-central bankers – of government bond yields. The central bank prints fiat currency, and then purchases its own bonds to artificially cap yields where they wish. Remember – when the price of the bond goes up, the yield goes down. This intervention weakens the domestic currency, ceteris paribus.

YCC -> Currency Weakness Playbook:

- The central bank caps the yield on one or more government bond maturities.

- The central bank stands ready to print money, which expands the money supply, so that it may purchase bonds in a quantity sufficient to reduce yields to below the cap.

- If the market believes that the yield should be higher than the YCC cap, then the central bank starts printing money until it either purchases all bonds outstanding, or the market stops demanding a yield above the cap.

- This process expands the money supply and thereby weakens fiat currency, due to the increased supply vs. real goods / services and other currencies.

Usually, Japan and the EU are happy to have a weak Yen or Euro vs. the rest of the developed world. It allows their export industries to gain market share, as their goods are cheaper vs. other countries. However, due to the food and fuel inflation experienced post-COVID and the cancelling of Russian commodity exports, their plebes are now facing the harsh downsides of having a weak currency. It is becoming more and more expensive for them to eat, move around, and heat/cool their dwellings.

The ruling bureaucrats of Japan and the EU have very strong political – and by political, I mean self-serving – reasons to continue YCC in the face of rising inflation that hurts 90% of their population. I will explore those motivations in greater detail later in this essay, but suffice to say that refusing to trade with Russia is a political choice, and one that Japan and the EU feel pressured to make in order to remain aligned with America. The combination of YCC and a boycott of Russian energy is a toxic cocktail, and if YCC is to continue, Japan and the EU will need a helping hand from their baby daddy, the US.

How can the US help? Let’s listen to former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke in a 2002 speech he gave before the National Economic Club.

The Fed can inject money into the economy in still other ways. For example, the Fed has the authority to buy foreign government debt, as well as domestic government debt. Potentially, this class of assets offers huge scope for Fed operations, as the quantity of foreign assets eligible for purchase by the Fed is several times the stock of U.S. government debt.

I need to tread carefully here. Because the economy is a complex and interconnected system, Fed purchases of the liabilities of foreign governments have the potential to affect a number of financial markets, including the market for foreign exchange. In the United States, the Department of the Treasury, not the Federal Reserve, is the lead agency for making international economic policy, including policy toward the dollar; and the Secretary of the Treasury has expressed the view that the determination of the value of the U.S. dollar should be left to free market forces. Moreover, since the United States is a large, relatively closed economy, manipulating the exchange value of the dollar would not be a particularly desirable way to fight domestic deflation, particularly given the range of other options available. Thus, I want to be absolutely clear that I am today neither forecasting nor recommending any attempt by U.S. policymakers to target the international value of the dollar.

At the direction of the US Treasury, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York trading desk could print USD, buy JPY/EUR, and purchase Japanese Government Bonds (JGB) or government bonds of EU members, parking them in the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) on its balance sheet. This has two positive effects. Firstly, this policy directly weakens the Dollar vs. the Yen and the Euro, which helps Japan and the EU import USD-priced commodities at cheaper prices. Secondly, this policy helps reduce government bond yields, but does not result in the growth of the balance sheets of either the Bank of Japan (BOJ) or the European Central Bank (ECB).

But, the Fed has also expressed interest in engaging in quantitative tightening (QT) to curtail domestic inflation and defend the wallets of the American people. QT (as defined by the Fed), is an activity whereby the central bank sells its holdings of US Treasury and Mortgage-backed Securities (MBS) for USD in order to tighten domestic credit conditions. If it’s more expensive for the government to borrow money, then it’s more expensive for American individuals and businesses as well. So the obvious question is, how can the Fed effectively engage in QT (i.e., tightening domestic USD credit conditions) while also loosening USD credit conditions globally by purchasing foreign government bonds?

Remember – politics is about accounting misdirection, not economic reality. In reality, engaging in the purchase of these foreign bonds will expand the USD money supply and the Fed balance sheet, and might nullify any impact its QT operations has upon domestic conditions. But that’s not how the Fed will spin it. Instead, the Fed can simultaneously sell its holdings of treasuries and MBS, while at the same time printing money to buy foreign bonds. And with a straight face, Powell can proclaim he is tightening US domestic monetary conditions to fight domestic inflation, while also helping America’s allies stay strong in the fight against Russia.

Fed Policy Rate (white); BOJ Policy Rate (yellow); ECB Policy Rate (green)

All three amigos – Japan, the EU, and the US – are experiencing record high inflation. However, only the Fed has increased policy rates to a meaningful degree thus far. Interest rate parity dictates that the currencies of countries that run the loosest relative monetary policies should weaken vs. those that run the strongest. Given that global commodities are priced in USD, the US’s tight monetary policies have created a situation wherein the US currently has the strongest fiat currency of the bunch. If the Fed stops raising and starts cutting its policy rates, this will weaken the USD vs. the JPY and EUR and reduce commodity prices for them.

The Fed can justify ending its tightening cycle by pointing to a looming economic recession in the US. If the Fed can credibly claim that inflation has peaked – i.e., the inflation rate slows enough that, even if prices continue to rise, they can say the worst is behind us – then they can switch to recession prevention mode without drawing too much ire from the public. “Recession prevention mode” is code for printing money – as the only way the Fed knows how to prevent a recession is to loosen monetary policy by turning on the printing press.

One or both of these setups is necessary for the Fed to be able to provide the allies of America with the liquidity they need to continue YCC. And if the Fed fails to do either, the discontent created in the EU and Japan by rising food and fuel prices (especially as fall and winter bring colder temperatures) might cause political difficulties for their respective ruling technocrats.

As crypto holders, the reason we care about YCC is that if/when either of these policy shifts is announced by the US Treasury, or we notice a rising ESF-reported balance, we can then assume that the Fed is actively engaging in printing money to aid the YCC efforts of Japan and the EU. Such activity would be highly inflationary and completely change the global fiat liquidity regime. With more fiat liquidity sloshing through the system, risk assets – which include cryptocurrencies – will find their bottom and quickly begin to recover as investors discover the central bank financial asset market put has been activated.

The following must be true for this hypothesis to be valid:

- America is committed to defeating Russia primarily using economic sanctions, which means its allies must refrain from purchasing Russian food and energy.

- Japan and the EU must pursue YCC to save their banking and political systems.

- The inflation driven by YCC is exacerbated by Russian food and energy sanctions.

- To keep their plebes from revolting, Japan and the EU need help from their ally, the US, to reduce their domestic inflation.

- Therefore, if America is to do right by her allies, she must find a way to print USD and purchase Japanese and EU bonds, or reduce the divergence in policy rates by starting to cut the Federal Funds rate.

- Printing USD to buy Japanese and EU bonds and/or cutting the Federal Funds rate weakens the dollar, and will add trillions worth of liquidity to the financial system. This fiat money will find its way into all-risk assets. PARTY TIME!

Shout Outs:

A huge thank you to Danielle DiMartino Booth from Quill Intelligence, my favourite OG volatility hedge fund manager, and Felix Zulauf. Danielle and the hedge fund manager helped to validate my thesis using their knowledge of the inner workings of the US Treasury and Fed. Danielle is a former Fed staffer, and the vol fund manager was a student of US Treasury Secretary and Former Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen. The data on the BOJ’s holdings of JGB’s was also compiled by a member of the same vol fund; his research saved my team a lot of time. Some of the charts listed are courtesy of Felix Zulauf’s most recent conference call.

Debt, Maths, and Exponents

As a species, homo sapiens aren’t particularly strong, fast, or agile. But what cements us as the apex predator and the ruler of our little gravity well are our language skills, which allow us to collectively organise. The social structures and governments that we form create the substrate that supports a large population and makes us productive.

It follows, then, that governments with the power of legalised violence and taxation can credibly borrow from our collective future in order to invest today. Its investments in services such as roads, schools, courts, hospitals, etc. are “paid for” by the increasing use of those services by a growing population (i.e., the economic benefits of more people using these services offset the costs). Or, if investments in these services drive an increase in societal productivity, then the debt is also “paid for” from an economic point of view.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a measure of activity, and a government will tax a portion of this activity to pay for the services it provides. So when one unit of debt generates more than one unit of economic output (in the form of a heightened GDP that the government can derive more taxes from), that debt is productive.

But, when one unit of debt generates less than one unit of economic output, governments get into trouble. It creates a situation wherein more debt must be issued to pay back maturing debt, kicking off a cycle that will lead to the government’s mathematical decline. The debt load will continue to grow exponentially, unless:

- The population grows such that more activity is generated, and more taxes are paid.

- A new technology or energy source is invented or discovered that dramatically increases the productivity of the current stock of workers. This raises the economic potential of society, and by extension, future tax revenues.

- The government defaults by:

- Issuing its own currency to nominally pay back the debt, creating inflation in the process.

- Outright cancelling debt via some sort of jubilee.

In this piece, I will evaluate the financial situations of Japan and the EU through the lens of population growth/decline and energy input costs – and I will demonstrate why they can’t repay their debt using options 1 or 2, leaving door number 3 (and more specifically, 3a) as their only realistic option.

I will argue that the only solution left for any governments of countries that are not productive is to pay back their debt loads by inflating them away. If the rate of interest on government debt is lower than the domestic GDP growth (i.e., negative real interest rates), then over time the Debt/GDP ratio will decline. GDP is just a measure of activity, and governments can create economic activity by issuing debt and spending this money on real stuff and services. Jobs 4 da boys and da girls. Da Bears!

Anyone who bought government bonds becomes a loser in real terms, as these schmucks are used to pay for the un-economic investments of the past. Private and public pensions are the easiest pools of capital to rob. That is because the financial regulators can stipulate that a certain percentage of their assets must be invested in government bonds that are designed to lose money in real terms over time. This gives the government a stationary target to fire monetary headshots at year after year until such time as the national debt load becomes manageable once more.

Exponential maths is apolitical. Exponential debt maths destroys governments with 100% certainty – the only question is how long it will take. When traders align themselves with maths, they must be patient. Politicians will attempt to use time against investors. They will inflict as much pain as possible today to push a darker future off to tomorrow, because that is all they can do. The future leads to ruin, and we just have to wait it out. YCC is the last gasp of a government caught in the clutches of exponential debt maths.

All the dominant economic “-isms” assume never ending growth. Therefore, if debt is expanding faster than economic growth, you just need to apply an infinite growth and time scale, and the government will default 100% of the time. Once new debt is needed to pay back old debt and the government budget is in deficit, time becomes deadly. This is the doom loop, and YCC is the only antidote. I will use this heuristic as a guide for determining whether or not a given government is in imminent danger of defaulting.

Demographics

When you live on the farm, children are free labour.

When you live in an apartment, children are expensive conversation pieces.

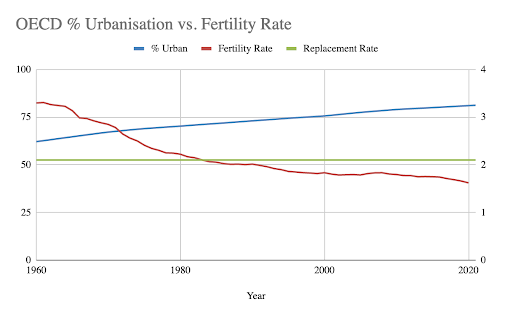

As shown above, as the developed world has urbanised, the birth rate has fallen well below the replacement rate. What was a post-WWII global baby boom became a modern day baby bust.

Demographic trends are slow moving, extremely powerful, and very difficult to change. Societal factors and the policies enacted by governments many decades ago are responsible for the demographic situation of today.

That is a very high-level overview of the macro demographic trends affecting all developed countries. Now, let’s dig into the specifics of the Japanese and European and their demographic situation.

When the number of productive members of society (the working age population, ages 15 – 64) increases, a country’s economic potential grows as well (and vice versa). Taking on debt when this cohort is growing makes sense. The country needs to invest in itself so that public services and institutions keep up with demand. However, when the working age cohort is shrinking, the country will lack the economic productivity to pay back issued debt in real terms.

The only ways to immediately augment a falling working age population are slavery and immigration. Developed countries did away with in-your-face slavery in the 19th century, meaning the only realistic near-term solution is immigration. But, there are also many cultural factors specific to each country that influence how their immigration policies are structured and how favourable (or unfavourable) they are to immigrants.

In Japanese, foreigners are called “gaijin”. While Japanese people are extremely polite and respectful to gaijin, they will never be considered full members of Japanese society because they weren’t born Japanese. The political leadership recognises the country is literally dying, but allowing millions of immigrants to immediately bolster the young working population is still not on the table.

The current crop of “enlightened” European technocrats in charge talk a big game about immigration, until cultural realities hit them in the face. Many of Europe’s values are derived from its countries’ shared Judeo-Christian history and system of beliefs. The Middle East and North Africa has a large pool of hungry, poor, and motivated individuals who would love a chance to improve their economic situation by moving to Europe – but their religious and cultural values stem from the Islamic tradition.

The cultural beliefs of Europeans and the Middle Eastern / North African peoples could not be more different. Try as the Davos crowd might, their countrymen will not accept boat and caravan loads of productive Muslim immigrants to fix Europe’s deleterious demographic situation. I actually doubt the Davos crowd would accept Fatimah and her brood at their swish Swiss chalets, either, but as the saying goes, “do as I say, not as I do.” Remember that the last time Europe faced an influx of Muslims (the Moors), the Roman Catholic Pope declared a Crusade to rid the Iberian Peninsula and other parts of Europe of the foreigners.

Japan and the countries of the EU need more users to generate the activity necessary to pay back the debt. Unfortunately, it simply isn’t possible – or at least, politically viable – for those countries to grow their user base quickly enough to escape the productivity decline death spiral.

Energy Policy

Another option that governments technically have for potentially outracing their growing debt loads is finding new, cheaper sources of energy with which they can drive increased productivity.

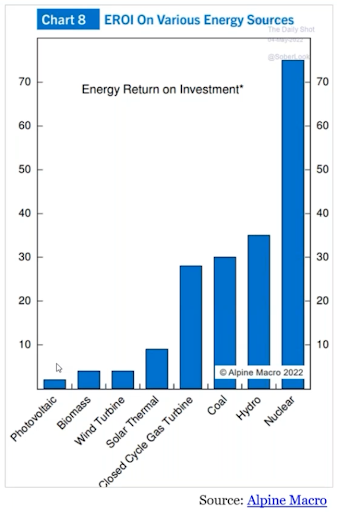

Thanks Felix for this chart.

Any country or economic bloc that refuses to embrace nuclear energy, is not naturally blessed with hydrocarbons, and/or believes renewable energy sources such as wind and solar are the path to energy self-sufficiency, isn’t versed in science and maths. That is the lesson to draw from the above chart.

Japan’s knee-jerk reaction to the Fukushima nuclear catastrophe after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami was to shut down all nuclear reactors. That has led the country to become even more heavily reliant on imported hydrocarbons. The result is that any disruption to the flow of energy will quickly cripple the Japanese economy, as it has no way to quickly produce energy internally.

As I wrote in “The Doom Loop”, Europe decided to outsource its energy policy to a Scandinavian high school student, and in the process became hooked on cheap Russian gas. Lo and behold, when the West froze the Russian state and citizens’ assets inside the Western financial system, Russia decided it was time for the EU to understand the consequences of their energy policy.

The continuation and escalation of the EU and Japan’s economic sanctions against Russia when, at least on paper, neither is actually at war with Russia, is a political decision to stay in the good graces of their security guarantor, America. America has its own ideological reasons for why it wants to use the sons of Ukraine and the finances of its allies to fight a proxy war with Russia, and they can also more easily bear the consequences of doing so. Americans might pay more for food and fuel as a result of sanctions, but they won’t starve or freeze. Boycotting Russia puts Europe and Japan in far more dangerous positions, as both need cheap energy to sustain their manufacturing prowess. But as dutiful allies, they must line up behind America in an attempt to economically blockade Russia. In the process, their already surging input prices (aka producer prices) will continue their asymptotic rise.

German Producer Price Index %YoY Change This data goes back to the 1970’s, and the current readings of +30% are the highest ever. How do you remain globally competitive with China when your input costs are surging to historic new heights?

This data goes back to the 1970’s, and the current readings of +30% are the highest ever. How do you remain globally competitive with China when your input costs are surging to historic new heights?

Meanwhile, China is feasting on discounted Russian energy because powerhouses like Germany refuse to purchase it.

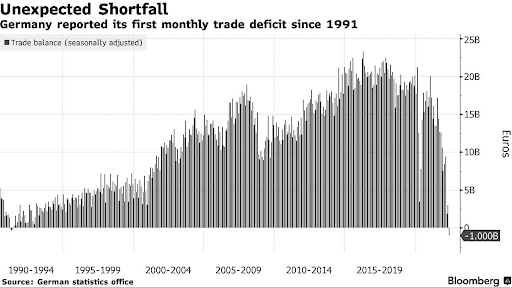

The chart below shows what has happened as a result.

Germany has its first monthly trade deficit in 30 years. Many large German industrial companies cannot survive without Russian natural gas. Germany’s – and by extension, Europe’s – financial position simply does not allow it to produce the same quantity of goods at the same price without cheap Russian gas.

Japan Producer Price Index %YoY Change

Japan is headed in the same direction as Germany. With input costs at their highest since the 1970’s, it too will become less competitive vs. China. Right now, the weak Yen is helping to soften the blow to some extent, but China will not stand by and allow the Yen to continue to weaken against the Yuan. China will devalue the Yuan vs. the Yen and the Euro, and Chinese exporters will pick up more business.

Japan is headed in the same direction as Germany. With input costs at their highest since the 1970’s, it too will become less competitive vs. China. Right now, the weak Yen is helping to soften the blow to some extent, but China will not stand by and allow the Yen to continue to weaken against the Yuan. China will devalue the Yuan vs. the Yen and the Euro, and Chinese exporters will pick up more business.

CNY/JPY Exchange Rate

A rising number means that the CNY is getting more expensive vs. the JPY.

Japanese and European input costs are not getting cheaper. Therefore, from an energy perspective, their economies are becoming less productive. The current policy of not purchasing Russian energy will cause the fundamental economic potential of these two economies to deteriorate further, and prevent them from outpacing their respective debt spirals.

Water Break

I hope that the preceding sections detailing the demographic and energy challenges that Japan and Europe face clearly show that debt payback via population growth or increased energy efficiency ain’t happening. So what sort of danger does that put them in?

Without a growing user base, there is no increase in activity for a government to tax. And as a government’s tax inflows stagnate or shrink, its debt servicing costs become unbearable. In a fractionalised financial system, the inability to service the debt kicks off the most dreaded outcome…deflation.

The central bank is tasked with preventing debt deflation. If the debt cannot be paid back in real terms, the debt assets underpinning the fiat fractional financial system go from being worth something to nothing. That starts a deleveraging process that will destroy the economy for asset holders (i.e., the folks that rule the world). As credit growth declines, so does business activity, and people lose their jobs. But if the business only existed because of cheap debt that could not generate the economic activity necessary to repay it, should that business exist? That is a philosophical question, and your “ism” belief system will inform your view on who should bear the losses from wasteful economic activity.

But regardless of what you think is fair or right, the reality is that these governments can’t just sit on their hands and watch their debt load spiral out of control – and at this point, inflation/hyperinflation is really the only available option from a political perspective.

Technically, the leaders of Japan and the EU have two remaining options: inflate away the debt, or accept a hard default. But given that the vast majority of government debt is held by either large banking institutions or the wealthiest citizens, outright default or debt cancellation is not preferred. That is because every unit of debt is someone else’s asset, and these assets are usually used as collateral for additional borrowings. Outright debt cancellation will thus have a significant negative impact on the government’s most powerful and wealthiest stakeholders, to whom they are typically the most beholden. So for most governments facing exponentially-growing debt loads and the choice between money printing and debt cancellation, it is much more palatable to just inflate away the debt by printing money, which hurts the plebes – who spend a disproportionate share of their income on food, fuel, and housing – instead.

The next two charts illustrate how Japan and the EU have clearly chosen to go the inflation route to offset their demographic and energy dilemmas.

OECD Japan Labour Force 15 – 65 (green), BOJ Total Assets (yellow), Japan GDP / Brent Crude Oil (white)

OECD Euro Area Labour Force 15 – 65 (green), ECB Total Assets (yellow), EU GDP / Brent Crude Oil (white)

In both Japan and the EU, the working age population (green lines) peaked and is in terminal decline, and the efficiency of one unit of GDP per unit of energy, aka oil, (white lines) has flatlined or is declining. The policy response is central bank money printing (yellow lines).

The two charts above clearly show that the powers that be would rather shift the debt restructuring costs to the poorest folks via inflation, rather than have their assets values marked down to levels that correspond with their real economic worth.

I will detail the political reasons why Japan and the EU will do more of the same by continuing with YCC policies (aka money printing) in the face of face-ripping inflation.

Yahweh of the Yen

The story of Japan’s descent into the deepest, darkest depths of profligate money printing began in the aftermath of its 1989 real estate crash. Japan’s solution for restructuring its economy was to print money in an attempt to combat the deflationary effects of a bursting asset bubble. Round after round of policies and academic sounding acronyms – all boiling down to “print more money” – were tried, until finally, the BOJ began manipulating the yield curve with price targets for various Japanese Government Bonds (JGB). And after thirty years, the BOJ has finally succeeded in producing the desired inflation.

YCC is very simple: if the yield on 10-year JGB is above 0.25%, the BOJ will buy an unlimited amount of JGBs until the yield falls to at or below 0.25%, or it runs out of JGBs to purchase. Therefore, the BOJ is willing to infinitely expand its balance sheet by printing JPY and purchasing JGB’s.

But the Yen does not exist in a vacuum. If the yield on JGB’s is markedly below other major currencies, then the exchange rate of the Yen will fall.

USDJPY Interest Rate Differential (10yr) vs. Exchange Rate

I plotted the 10-year yield differential between US Treasuries and JGB’s in white. The yellow line is the USDJPY exchange rate. If that yellow line is rising, it means the JPY is weakening. As US interest rates rise due to the Fed raising its policy rates, the JPY rate tries to follow– but the BOJ stomps it down to a maximum of 0.25% with its YCC policy. The widening gap results in the JPY weakening.

The weakening Yen is a political problem for the government because Japan imports nearly all of its energy. Remember – Japan shut down all its nuclear reactors post-2011, leaving it with few options for homebrewing its own power supply.

Brent Crude Oil in JPY Terms

Oil priced in Yen is up 65% YoY. That is extremely painful for Japanese manufacturers and consumers. Companies are starting to raise prices for the first time in a long time. There is nothing better than washing down a sumptuous bowl of ramen with an Asahi – but it’s going to be costing you a lot more in the near future.

“Asahi Breweries will increase prices across the vast majority of its beverage lineup, passing on surging ingredient and packaging costs to customers in a move that could spur rivals to follow suit.

The hikes announced Tuesday, set to take effect Oct. 1, span 162 products including the flagship Asahi Super Dry beer…[the] first increase in consumer prices since 2008″

Japan is notionally a democracy, but the ruling party, the LDP (Liberal Democratic Party), just won a super majority in the Diet at last weekend’s election. So while the plebes might be getting a bit antsy in the face of skyrocketing inflation, the entrenched political elite is very unlikely to lose their jobs. The YCC madness is therefore likely to continue – but what does the BOJ gain from pursuing such a policy?

I used the handy <SRCH> function on Bloomberg to analyse all the JGBs outstanding. Currently, there are JPY 1,020 trillion worth of JGBs outstanding (this is the par value of bonds issued). These bonds pay coupons semi-annually, which total JPY 15.45 trillion.

Interest payments do not consume the totality of tax revenues. Interest rates would need to rise quite substantially before the debt costs more to service than tax revenue. The government can take a small amount of solace that its debt position isn’t terminal just yet.

|

Total JGB Outstanding (JPY trn) |

1,020 |

|

Yearly Coupon Payments (JPY trn) |

15.45 |

|

% of 2022 expected GDP |

2.83% |

|

% of 2022 Budget |

14.36% |

|

% of 2022 expected Tax Revenue |

23.70% |

The government could take some political heat off of itself by cajoling the BOJ into ending YCC and still afford to pay its bills. So if it’s not on the brink of default, why is the BOJ continuing with this policy?

I sat down with my favourite vol hedge fund manager and asked him this question. Given that he has been trading JGB’s for almost as long as I have been ex-utero, he knows a thing or two.

According to him, the BOJ’s current YCC policy stance is all about the solvency of the domestic commercial banking system. Let’s dive in.

Due to poor growth, poor demographics, and financial repression, yields on banking deposits are practically zero in Japan. This is not much different than most North and East Asian exporting powerhouses.

Since the early 1990’s, the BOJ has strived to ignite the animal spirits of Japanese households by doing everything in its power to force Mrs. Watanabe to spend money. To accomplish this goal, the BOJ punished savers by dropping its policy rate lower and lower until it finally entered negative territory over the past 10 years or so. Japan’s citizens worked diligently, and when it came time to save the surplus of their efforts, the banks in some cases charged them for the privilege – because they in turn were charged by the BOJ to deposit money with the central bank.

Negative interest rates are toxic for both savers and commercial banks. Therefore, the BOJ must ensure that the banks, who are the only stakeholders the BOJ really cares about, remain profitable. To do that, the BOJ targets the yield on various maturities of government bonds. The goal is to create a steep yield curve whereby long-term deposit and lending rates are higher than short-term ones. Given that banks borrow short from depositors and lend long to businesses, they are guaranteed to make money on the spread.

The yields in Japan were and are extremely meagre. To jazz up their product offerings, banks began offering a wide variety of structured products that enhanced the yields on deposits. Essentially, the customer sells an option to the bank, and picks up a slight amount of premium income, which raises the effective deposit rate. The bank earns a healthy spread on the implied volatility of the option. The customer always sells volatility cheaply to the bank, who then offloads it to the wider market of professional investors and traders.

The simplest – and most widely issued – product is a callable deposit. Imagine you walk into the bank, and the friendly teller says that instead of earning 0% on your deposit, you can enter into this 1-year-callable, 20-year deposit and earn an extra 0.25% per year on your money. Every year, the bank has the option to call back the deposit if interest rates fall – and of course, if the customer wants to exit the structure and earn less on a normal deposit, the bank will happily oblige. If interest rates keep falling or are below the strike price of the option (let’s say it was a yield of 0.25%), then the customer effectively locks up their money for one year at a time for twenty years. And because interest rates in Japan fell or flatlined for three decades, customers view this product as a one-year deposit, not a twenty-year deposit.

HOWEVERRRRRRR, if interest rates buck the trend and actually rise, what the customer thought was a short-term deposit now becomes a very long one instead. Staying with the same example, consider if interest rates in year one rose above 0.25%. The customer is now locked into a nineteen-year deposit at a fixed rate of 0.25%. Even if next year’s rates are at 1%, the customer still earns only 0.25%. And that’s not even the worst part – if the customer was accustomed to viewing this product as a one-year deposit, but now can’t access their money for another nineteen years, I suspect they might be slightly agitated.

Remember the terrible demographics of Japan. Who do you think has most of the financial assets in the land of the rising sun? It’s old folks on fixed incomes. Nan-nan and Pop-pop thought they were maximising their income stream, and instead now lost access to their nest egg. How will they pay for the rising cost of goods now that the BOJ has succeeded in generating the highest inflation and lowest value of the Yen in over thirty years?

Table your concerns for the broader citizenry for a moment, and let’s return to the all-important banks.

The banks hedge their callable deposits and other funky structured products in the fixed income derivatives markets. Even I don’t fully understand the maths and option greeks behind the exposures generated by these products, but the simple fact is that the bank does not warehouse this risk on its balance sheet. The bank goes into the market and hedges itself.

Given that the BOJ fixed the rate of the ten-year JGB, a lot of trading happened with products in the ten-year maturity bucket. That pin risk around the 0.25% yield on the ten-year JGB means that should that peg break, banks will turn from sellers of volatility at that maturity to buyers. That wouldn’t be such an issue if the size of the cash or spot JGB market was roughly equal to the amount of derivatives written on it. But the size of the JPY interest rate derivatives market dwarfs the amount of JGB’s issued. That means if the banks all turn into buyers at the same time, there will be no one on the other side to let them out of their trades until the effective yields are multiples higher than where they are today. If the BOJ does not hold the line at 0.25% on the ten-year JGB, the banks stand to lose billions of dollars delta-hedging their interest rate exposure into an illiquid market. The BOJ is acutely aware of the consequences to its most important stakeholders should the central bank fail to maintain the YCC peg.

While “billions” is my extremely rough guestimate of the potential banking losses, no one knows the true extent of the interest rate risk embedded in the Japanese banking system. One of the vol fund’s traders pointed out that these structured deposits are not reported in the bank’s financial results, which detail their net interest margins. He also noted that the dealing desks of the banks don’t like talking about their exposure to such products. So while we know trillions of Yen of these products have been issued, not even the regulator has a handle on just how exposed the banking system it supervises would be should interest rates rise.

Back to the plebes with banking deposits. If you are now locked into a long-term deposit but need the money today, you’ll ask that friendly bank teller, “Hey – can I exit the trade early?” And the answer will be, of course you can – but there’s going to be a cost.

The current 20-year JGB yields approximately 0.95%. For illustration purposes, I’m going to simplify the bond maths. Let’s assume you have a 0.95% yielding 20-year zero-coupon bond with a face value of 100 JPY, and interest rates rise 1%. What happens to the price of the bond?

|

Yield |

0.95% |

1.95% |

|

Years to Maturity |

20 |

20 |

|

Face Value (JPY) |

100 |

100 |

|

Present Value |

83 |

68 |

|

Difference |

-18% |

Present Value Zero-Coupon Bond = Face Value / [(1 + Interest Rate) ^ Years to Maturity]

The bank teller scurries back and informs you that it will cost 18% of the value of your deposit to get your money back today. WTF!!!

“But I need that money to pay for higher gas and fuel prices!” the customer cries out in agony.

The bank teller will politely concoct a word salad that amounts to “tough shit!”

The bank has to go back into the market and unwind all its hedges at an interest rate that is much higher than the strike price of the structured product it sold to its customers. The bank simply isn’t going to take the loss for the product performing as advertised. And while they are contractually allowed to do that, it would be a horrendous move from a political standpoint.

Imagine if all the plebes living on incomes that haven’t risen in three decades now face losing 20% or more of their deposits to withdraw their money from the banks that profited from the manipulated interest rate regime engineered by the BOJ. That is a political nightmare for the government. But, that’s what governments are there to do – decide who bears the loss. It’s ultimately a political question, and I have no idea how it would really play out.

Instead of committing political suicide by sticking stakeholders with the losses stemming from the BOJ losing control of the JPY interest rate markets, the BOJ can just choose not to lose control of the interest rate market. Remember, the interest rate peg is a political construction– it’s uneconomic, but continues because politics dictates that it is the path of least resistance to surreptitiously assign the losses of the 1989 real estate crisis and a dying workforce to the broader population through negative real rates and financial repression. If the BOJ boldly claims it will continue with YCC no matter what, then the peg never breaks…at least in the mind of Kurodo-dono. If the peg doesn’t break, none of these undesirable outcomes vis-a-vis the callable deposits and other products of its ilk come to pass. It’s so simple, right?

The holy trinity of monetary policy cannot be violated no matter how many peer-reviewed economic papers you publish arguing the opposite. You cannot simultaneously have a freely traded currency, fixed interest rates, and an independent monetary policy. The market clearly will not purchase 10-year JGBs at a yield of 0.25%, and the BOJ must therefore buy all the bonds issued by the government.

The BOJ has a big problem. It is running out of bonds to buy.

|

BOJ Holdings of 10 year JGB |

||

|

10-June-2022 |

30-June-2022 |

Amount Purchased |

|

68% |

71% |

6.14 JPY Trillion |

This is what happens when YCC goes awry. The JGB market is one of the largest bond markets globally, and in 20 days the BOJ purchased 3% of the outstanding 10-year bonds in order to continue its market manipulation.

The government must issue more bonds – i.e., increase the national debt – so that the BOJ can buy them to maintain their 0.25% target. The government uses the newly minted Yen from this process to placate the population with various deficit spending measures. One example would be their subsidising of the gas, heat, and electricity bills of consumers. And as the JPY money supply increases, the Yen weakens against other global currencies.

But at some point those selling commodities to Japan will demand a “hard” currency, which the government cannot print out of thin air. At that point, the jig will be up, and prices will spiral out of control inside of Japan. This is just maths, and again, hyperinflation is a political choice to delay the inevitable. The losses for events that transpired many decades ago will get recognised eventually. The only unknown is who will bear the costs.

If Japan didn’t have to import most of its energy, this YCC game could be continued for much longer before hitting the inflection point it’s arriving at today. However, Japan is not naturally blessed with energy, and it is an ally of America, which means it cannot buy heavily discounted Russian energy. America will be called upon to figure out a way to help its ally, or Japan will face an uprising of angry voters fed up with the inflation that is being forced on them by the ruling elite. I don’t know what the ruling party will choose, but it won’t be an easy decision to make. It would be much simpler if America stepped up the plate.

Nothing to See Here

“Yellen Shows No Willingness to Consider Intervention for Yen” – Bloomberg, 12 July 2022

A Treasury-led, Fed-executed intervention to weaken the Dollar against the Yen is exactly what is being considered. This is a trial balloon to see how the market reacts to the possibility that America rides to the rescue of its ally.

Treasury Secretary Yellen and her Japanese counterpart met and discussed many things. But obviously, the most pressing issue for the Japanese is the international value of its currency. If the BOJ is wedded to YCC in order to save its banking system, then the only way to prop up the value of the Yen and reduce import costs is for America to print Dollars to buy Yen.

This scenario is 100% in play regardless of the bold-faced denial, and we shall soon witness the slew of anointed economists debating the merits of such a policy. If the market mummers are favourable, prepare your butts for an intervention.

Part Deux

Digest this missive, and stay tuned for the next instalment of this tale where I shall describe the situation in the kingdom of the Euro, how the Fed will engage in accounting tricks to save its allies, and finally, why all this will levitate crypto out of the current nuclear bear market.

We know why Kuroda-dono is so desperate for help from Sir Powell, but what about Lady Lagarde? Find out next week why the EU situation is no less dire than that of Japan.

YCC is definitely in play and one only has to observe the continued depreciation of the Yen and Euro vs. the Dollar. Sir Powell, mount up! Rest up weary readers, for there is much more to witness on the road to hyperinflation.