Abstract: We analyse the idea of Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). We divide the concept into two distinct ideas: i) Banning physical cash, and, ii) Allowing retail customers to have deposits directly with the central bank. We conclude that although in some ways the two policies complement each other, they have vastly different economic consequences. The former would increase credit expansion, and the latter would cause contraction. Due to the deflationary nature of allowing the public to hold electronic deposits at their central bank, we think financial regulators are unlikely to allow these CBDC schemes to succeed in any meaningful way.

Overview

Over the past year or so, there has been a considerable pickup in talk about Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). One could interpret CBDC simply as banning physical cash, thereby making money 100% electronic. Since physical cash is already quite rare, at least in certain jurisdictions, this could be achieved without making any significant changes to the existing electronic money infrastructure at all. The other and more popular interpretation of CBDC is allowing the general public to have electronic deposits placed directly at the central bank. This could either complement the first policy of banning cash or operate as an independent alternative, whilst cash is still in existence.

After reviewing the economic interpretations of CBDC in this piece, in a second piece, we will move on to some of the technological interpretations, often linked to the idea of financial institutions using aspects of “blockchain technology” or “distributed ledger technology” (DLT). The economic and technical interpretations are often erroneously bundled together, however in our view they should be considered entirely separately. CBDC can be achieved almost entirely without blockchain technology, while at the same time, any benefits of blockchain technology can be achieved independently of CBDC.

Economic Overview

Before evaluating the efficacy of this proposal, it is vital to understand the mechanics of the global financial system. We touched on this topic back in October 2017. The key driver of modern economies is the credit cycle, namely whether commercial banks are expanding or contracting their balance sheets. Banks expand their balance sheets by making new loans, which from their point of view creates new assets (the loan) and new liabilities (the corresponding deposits). From a liquidity perspective, the largest deposit-taking institutions in an economy have an almost unconstrained capability to create new loans, since the funds loaned out will automatically get placed back into their own bank as a deposit.

Currently there is one exception to the above, depositors can withdraw their deposits from the banks in the form of physical cash. This is something that banks need to finance out of reserves. Therefore, if the public removes funds from the banking system, in the form of physical cash, banks’ ability to make new loans is constrained. There are of course other non-liquidity-based constraints on credit expansion, such as capital ratio regulation.

Please note that withdrawing funds from the bank, by means of an international wire transfer, does not constrain a large bank’s ability to make loans. The purchase of foreign currency is a two-way trade, one party sells the local currency and while another party is a buyer, this buyer would then keep the funds on deposit (perhaps indirectly) in the same large banks. Therefore physical cash is in somewhat of a unique position, it is the only way, from a systemwide perspective, that the liquidity needs of the largest banks in an economy can be tested. Of course this is a pretty weak test, as nobody is going to want to withdraw millions of dollars in physical cash for a variety of reasons (e.g. security) and therefore large banks are in an immensely powerful position and their decisions to make loans are the primary driver of modern economic cycles.

It is within this framework that one should analyse our two categories of CBDC, banning cash and allowing retail customers the ability to directly deposit funds at the central bank. Banning cash removes the one remaining liquidity constraint on the banks, allowing them to expand credit and create new money, almost at will. On the other hand, allowing the general public to make electronic deposits at the central bank provides an extremely powerful way for people to exit the commercial banking system, which is likely to heavily constrain the banks’ ability to create credit.

Potential Economic Interpretations of CBDCs

|

Policy |

Impact on commercial banks |

Impact on the economy |

|

The banning of physical cash |

Bank balance sheets expand |

Inflation |

|

Central bank deposit accounts made directly available to the general public |

Bank balance sheets contract |

Deflation |

Banning Physical Cash

In our view, of the two policies, banning physical cash is more likely to occur in the medium term. At least, the banning of cash seems reasonably consistent with other political and economic trends, namely:

- Increases in experimental and expansionary monetary policy

- Increased state surveillance

- Increased use of the internet and electronic systems

- Increased levels of protection for the banking system

- Increased levels of state power

In favour of banning physical cash | Against banning physical cash |

|

|

Perhaps the most significant argument in favour of banning cash, is the usage of cash by criminals. The data on the subject looks quite compelling. According to US government data, in 1976 around 25% of US cash was in $100 bills, while today it’s around 80% the reason being that higher-denomination bills are more popular among criminals.

There are some regions like the midwest that have almost no demand for $100 bills, but what we found was a really interesting pattern involving border states like Florida, California and Texas, that were basically, it turned out,heavily involved in drug trafficking…The stuff is being sold on the street for tens and twenties. They bring it down [to the border states], and they convert it and pay it into the banking system and get larger bills that are easier to ship out

(Source: James Henry – Senior fellow at Columbia University’s Center for Sustainable Development)

Kenneth Rogoff is the former chief economist at the IMF and a prominent advocate of banning cash, at least in stages, with higher denomination bills being banned first. Criminal usages of cash is also a key reason for his objection to paper bills.

It just plays a huge role in crime, there are just lots of ways to conduct crime, you can use uncut diamonds, you can use gold coins, you can use cryptocurrencies, but you just cannot scale them the same way, simply because these other things are not that easy to spend in the economy

(Source: Ken Rogoff)

And of course there is the case built around monetary policy:

interest rates are stuck at zero and there are certainly a lot of economists and central-bank researchers who’ve argued that at the peak of the Great Recession, it would have been nice if they could have cut interest rates even more than they did below zero, maybe even to minus 2% to minus 4%, to try to just jump-start the economy, keep inflation up, keep employment up… Why didn’t they even really consider it? They didn’t do it because there is paper currency, and central bankers rightly worry that if they set interest rates really negative and people thought they would sit there for a long time, there’d be this mad dash into cash which would, first of all, eviscerate the policy, because interest rates wouldn’t go down, and second of all, create all kinds of chaos with that much cash floating around.

(Source: Ken Rogoff)

However, even Mr Rogoff appreciates that cash has some strong advantages that electronic systems cannot compete with, namely the high degree of robustness of the physical system, or as he puts it, the ability to function in a storm.

I would leave the smaller notes around just because we’re still far from solving perfectly some of the problems about what to do in a storm, privacy, small transactions; you want to send Junior to the store for candy and don’t want to give them a credit card.

(Source: Ken Rogoff)

For a more complete explanation of the case against physical cash, we would recommend Ken Rogoff’s book, The Curse of Cash. Banning cash in the short term is unlikely, however, it is easy to see how this viewpoint slowly begins to gain political traction, especially if electronic payment systems gain in popularity and therefore criminal usage of cash as a proportion continues to grow.

Such a policy would of course be a positive for electronic cash systems like Bitcoin. The US Dollar is essentially an electronic money system, with a two-way pegged, anonymous, credit risk-free, censorship-resistant and extremely widely-adopted sidechain, called physical cash. This makes the US Dollar highly compelling when compared to electronic cash systems like Bitcoin. Removing the physical “sidechain” would make Bitcoin a lot more attractive, relatively speaking.

Central bank accounts made directly available to the public

Currently only large financial institutions are able to have electronic deposits at the central bank, this normally includes banks, credit unions, broker dealers, and payment service providers. The idea behind this policy would be to expand this privileged status to the general public. Of course, the general public can already have deposits at the central bank, but only physically via cash, this would allow the public to have electronic deposits at the central bank.

In favour | Against |

|

|

As we explained above, unlike banning cash, in our view, due to the contractionary nature of the policy, it represents a reversal of political and economic trends most economies have been moving in. As the British central bank said in a report published as recently as March 2020 said:

If significant deposit balances are moved from commercial banks into CBDC, it could have implications for the balance sheets of commercial banks and the Bank of England, the amount of credit provided by banks to the wider economy, and how the Bank implements monetary policy and supports financial stability. Nonetheless, CBDC can be designed in ways that would help mitigate these risks

Source: Bank Of England

The report goes on to say:

If, during a period of stress or financial uncertainty, households and businesses saw CBDC as less risky than commercial bank deposits (notwithstanding that retail depositors enjoy FSCS protections), that rush to safety could trigger broader systemic instability. In that sense, a period of rapid substitution from deposits to CBDC would be equivalent to a run on the banking system. This could in principle happen today through a run from deposits to cash, but runs to cash are limited by the practical frictions and costs involved in withdrawing and storing large amounts of cash

It is for this reason that we do not think such a policy will fly, at least in most jurisdictions.

Ecuador

The above ideas may seem somewhat extreme. However, an experiment similar to this has been conducted before, by Ecuador, as CNBC announced in 2015, “Ecuador becomes the first country to roll out its own digital cash”.

In the late 1990 Ecuador suffered from hyperinflation and as a result the economy dollarized. The local currency, the Sucre, was withdrawn from circulation (In September 2000) and ever since the economy has officially used the US Dollar. Therefore, although the government launched a digital only currency in 2015, the main currency in the economy, the US dollar, was still available in physical form with US government issued paper. The digital money system was US Dollar-denominated, issued by the Ecuadorian government. Therefore the electronic money system was exposed to the credit risk of the Ecuadorian government and there was no physical cash alternative with the same credit risk. This doesn’t fit perfectly into the categories we have talked about in this report, but it is reasonably analogous.

The system eventually shut down in 2018, due to a lack of user demand. When analysing the scheme in 2014, academic Lawrence White noted:

There is no reason to believe that a national government can run a mobile payment system more efficiently than private firms like Vodafone…

(Source: Dollarization and Free Choice in Currency)

In the end this project is estimated to have cost the government around $8 million and it can not be said to have achieved much, other than perhaps providing a lesson for other central banks.

Sweden

Another interesting case study is that of Sweden. In 2009 a criminal gang conducted a daring raid on a cash depot using a helicopter, stealing millions of dollars worth of Swedish Krona. Some economists think this incident took Sweden by surprise and turned public opinion against cash, to some extent, to discourage this type of violent crime. Cash usage in Sweden is one of the lowest in the world, both as a proportion of transactions and proportion of reserves. According to the Swedish central bank, cash in circulation as a percentage of GDP is below 2%, compared to around 7% in the US and 9% in the EU. The Swedish central bank has already withdrawn the highest denomination bills from circulation and cash usage is declining at a fast pace.

[In] 2018, only 13 per cent paid for their most recent purchase in cash. The corresponding figure for 2010 was 39 per cent. As more consumers turn to electronic payments, it will ultimately no longer be profitable for retailers to accept cash. If the trend continues, Sweden may find itself in a few years’ time in a position where cash is no longer generally accepted by households and retailers

(Source: The Swedish central bank)

Since 2017 the Swedish central bank has been researching its proposed E-krona project, a CBDC project aimed at complementing the withdrawal of physical cash from circulation. As of February 2020, the bank is partnering with Accenture to offer a pilot E-krona system. The pilot documentation mentions the use of “block-chain technology”

This technical solution will be based on Distributed Ledger technology (DLT), often referred to as block-chain technology

(Source: The Swedish central bank)

In our view, the usage of the term block-chain may be an indication that the project is a long way off implementation. We predict that the project will continue, but eventually the Swedish central bank will remove references to DLT and blockchain, as the Bank of England appeared to do so in its latest report, as the British bank intelligently put it:

We do not presume that CBDC must be built using Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), and there is no inherent reason it could not be built using more conventional centralised technology.

Source: Bank Of England

Despite this, given the political and economic circumstances in Sweden and the much stronger stance in favour of this policy from government institutions, Sweden could be the next country that launches a CBDC.

Conclusion

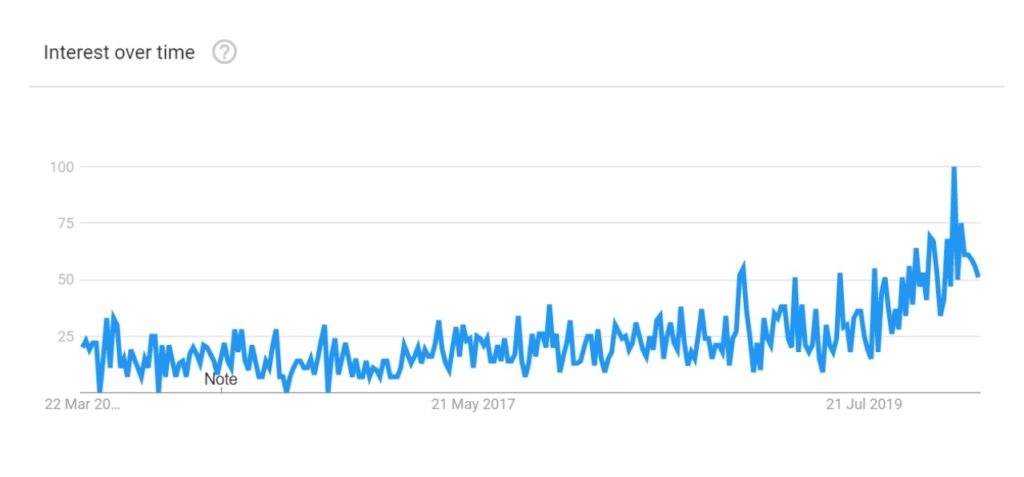

Bitcoin, blockchain technology and perhaps stablecoins such as Tether appear to be partly responsible for increased interest in the CBDC idea over the past year or so. The Bank of International Settlements, the Bank of England, Sweden’s Risbank and the European central bank have all recently published research or toyed with the idea.

Interest in CBDC over time

(Source: Google Trends)

CBDCs may have some limited success in small and wealthy jurisdictions like Sweden, however in our view the incentive to protect the commercial banks from runs will eventually outweigh all other considerations. Therefore we think it’s unlikely that CBDC will develop in any meaningful way in a significant jurisdiction. At least while the current economic paradigm of financial crashes, followed by highly expansionary monetary policy, continues.