Abstract: In this piece we look back at the history of Bitcoin, focusing in on “The Bitcoin Foundation”, once one of the most prominent organisations in the ecosystem. We look at Foundation’s origins and then examine its failings with respect to its governance, transparency and finances, which ultimately led to a total loss of legitimacy within the Bitcoin community. We conclude that an all-encompassing Foundation was never likely to have been a good idea given the high governance and transparency standards of some in the community, and that a constant stream of scandals damaged the Foundation’s brand to such an extent that its duties had to be carried out by other organisations.

(Screenshot of the Bitcoin Foundation’s website and logo in 2013)

The Foundation’s Origins

Following on from our July 2018 piece, which took us back to shenanigans and incompetence at MtGox in 2011, this second look at Bitcoin’s scandal-rich history takes us back to July 2012, when The Bitcoin Foundation was founded. The Foundation had seven founding members, or six if you exclude Satoshi, who was oddly included as a founding member.

Bitcoin Foundation Founding Members

- Gavin Andresen, Bitcoin Developer

- Peter Vessenes, CEO of CoinLab

- Charles Shrem, CEO of BitInstant

- Roger Ver, CEO of MemoryDealers

- Patrick Murck, Principal at Engage Legal

- Mark Karpeles, CEO of MtGox.com

- Satoshi Nakamoto, author of the white paper “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System”

(Source: GitHub)

The objective of the Foundation was never completely clear, with the original bylaws stating the following:

The Corporation shall promote and protect both the decentralized, distributed and private nature of the Bitcoin distributed-digital currency and transaction system as well as individual choice, participation and financial privacy when using such systems. The Corporation shall further require that any distributed-digital currency falling within the ambit of the Corporation’s purpose be decentralized, distributed and private and that it support individual choice, participation and financial privacy.

(Source: GitHub)

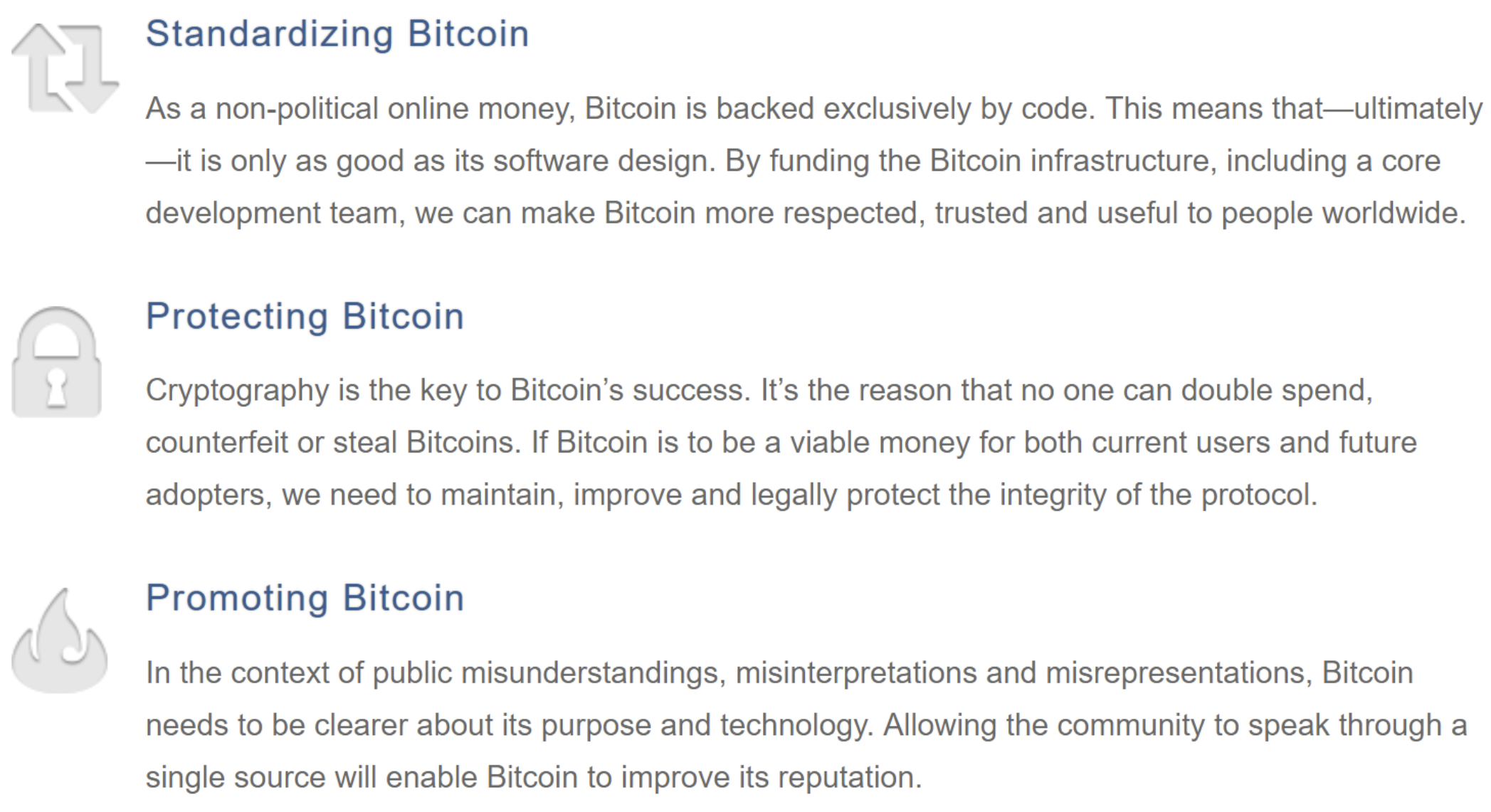

The Foundation’s Mission – June 2013

(Source: The Bitcoin Foundation)

In practise the role of the Foundation appeared to be as follows:

- To pay the salary of Bitcoin developer Gavin Andresen

- To arrange Bitcoin conferences

- To promote Bitcoin to regulators

During 2012 and 2013 the Foundation gained in popularity, attracting members from across the Bitcoin community, including prominent developers, businesses and community members.

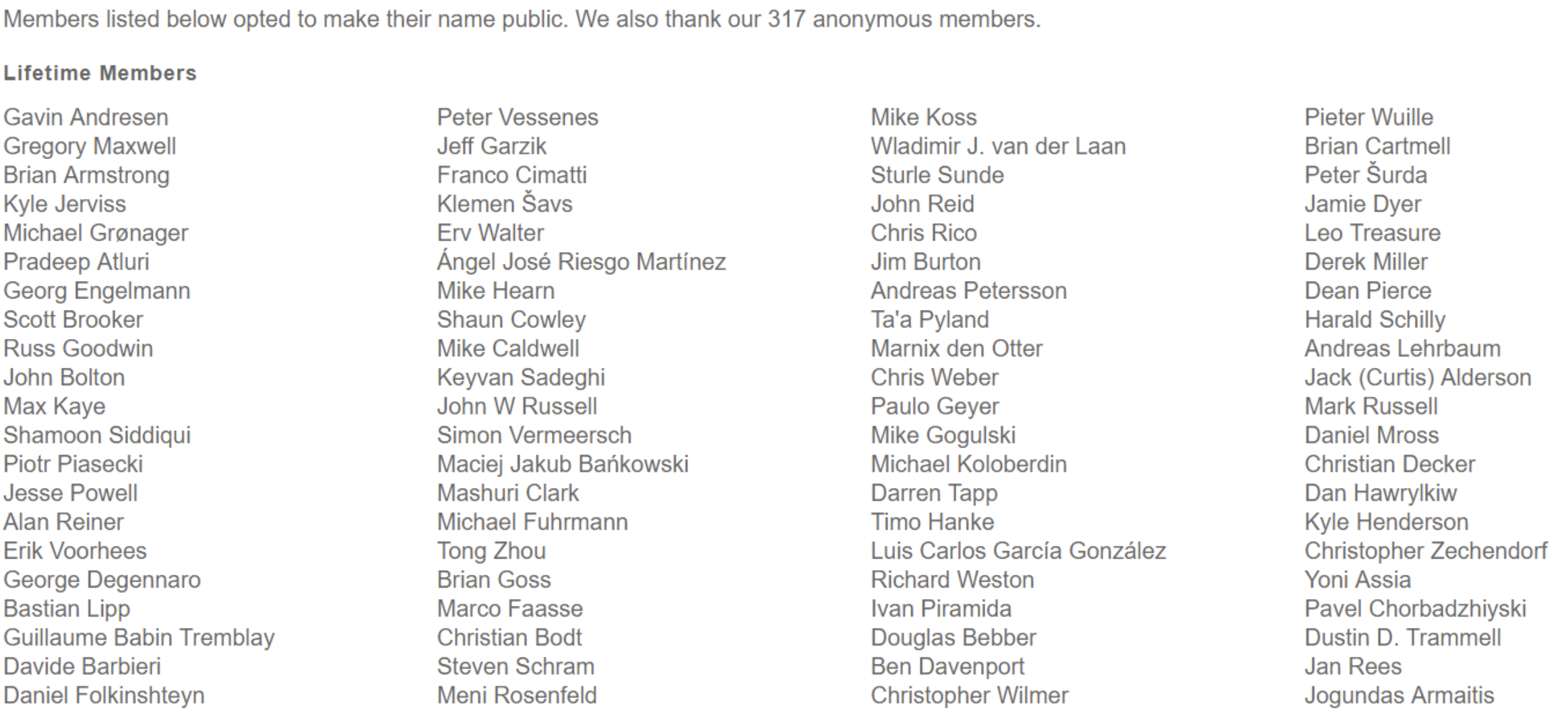

Public list of individual lifetime members

(Source: Bitcoin Foundation)

Corporate members as at September 2013

(Source: Bitcoin Foundation)

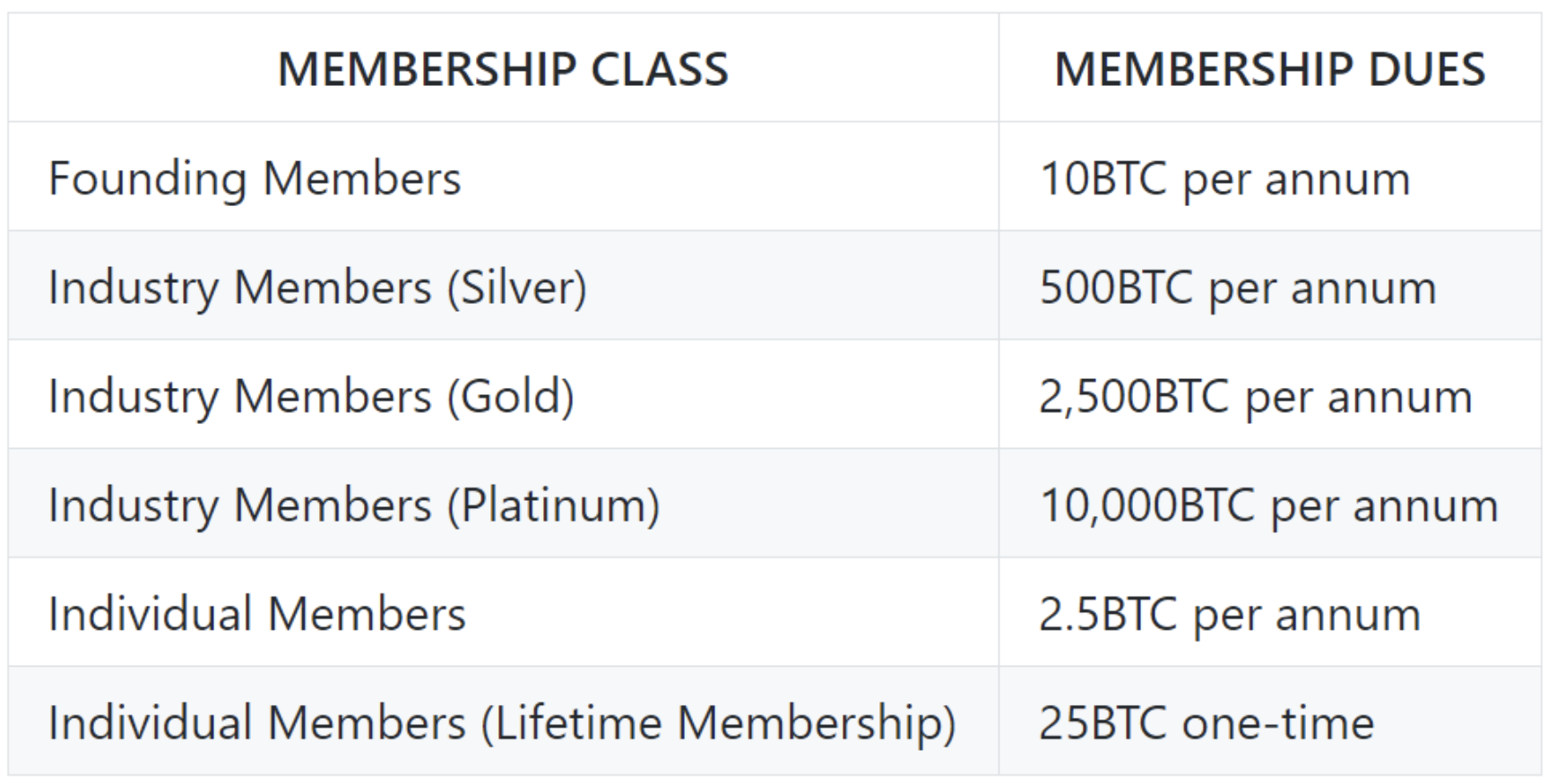

The Foundation was funded by membership fees – the initial membership fee schedule is provided below. However, the Bitcoin-denominated prices did start to decline in 2013 as the Bitcoin price appreciated.

Initial Membership Fee Schedule

(Source: GitHub)

It was believed by many that due to the membership subscription fees, the Foundation had considerable financial resources to spend on its mission.

Approximate lower bound of member contributions in April 2013 (Assuming initial fee rates)

- 2 Platinum Industry Members * 10,000 BTC = 20,000 BTC

- 7 Silver Industry Members * 500BTC = 3,500 BTC

- 175 Lifetime Members * 25BTC = 4,375 BTC

- Total Resources = 27,873 BTC

(Source: BitMEX Research)

As we see later on in this report, the Foundation only had around 8,000 BTC at the end of 2012, still a nice warchest, but a lower balance than many had expected. It is possible our estimate above could be an overestimate, as the timing of member subscriptions is unclear.

The Foundation Board

The governance structure of the Foundation was quite complex and arcane. There were three classes of members:

- Founders

- Individuals

- Corporates

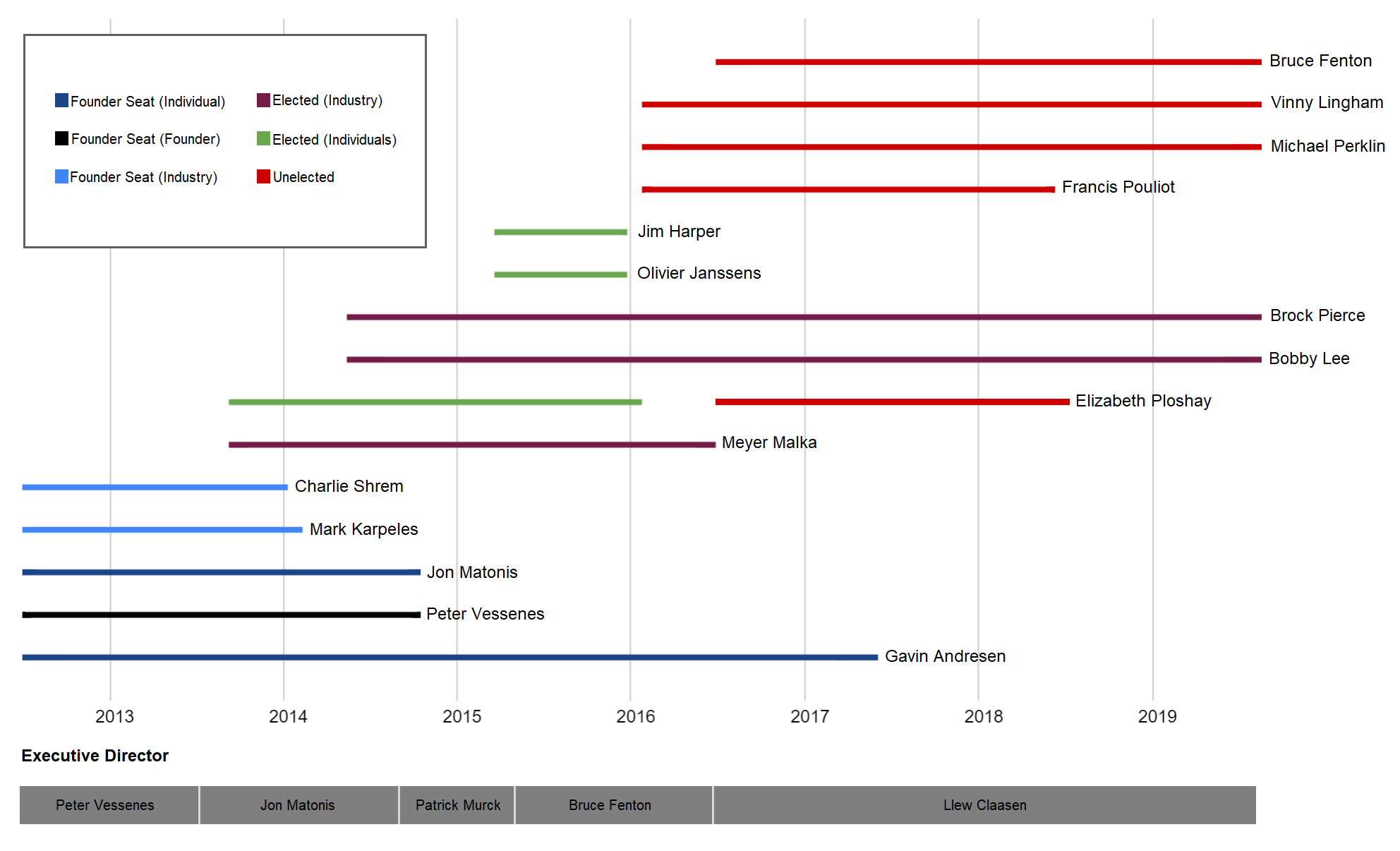

The board initially consisted of five members, one nominated by the founders, two nominated by individuals and two nominated by corporate members. The term of each appointee was expected to be 3 years. At the start of the Foundation, all five board members were appointed by the founders and all board members were founders, with the exception of Jon Matonis.

Bitcoin Foundation Board Members (2012 to 2019)

(Source: Bitcoin Foundation Website, BitMEX Research)

Critics can point to the fact that the governance structure gave too much power to the initial founders and that new members of the organisation should have been able to join as equals to the founders.

Board Elections

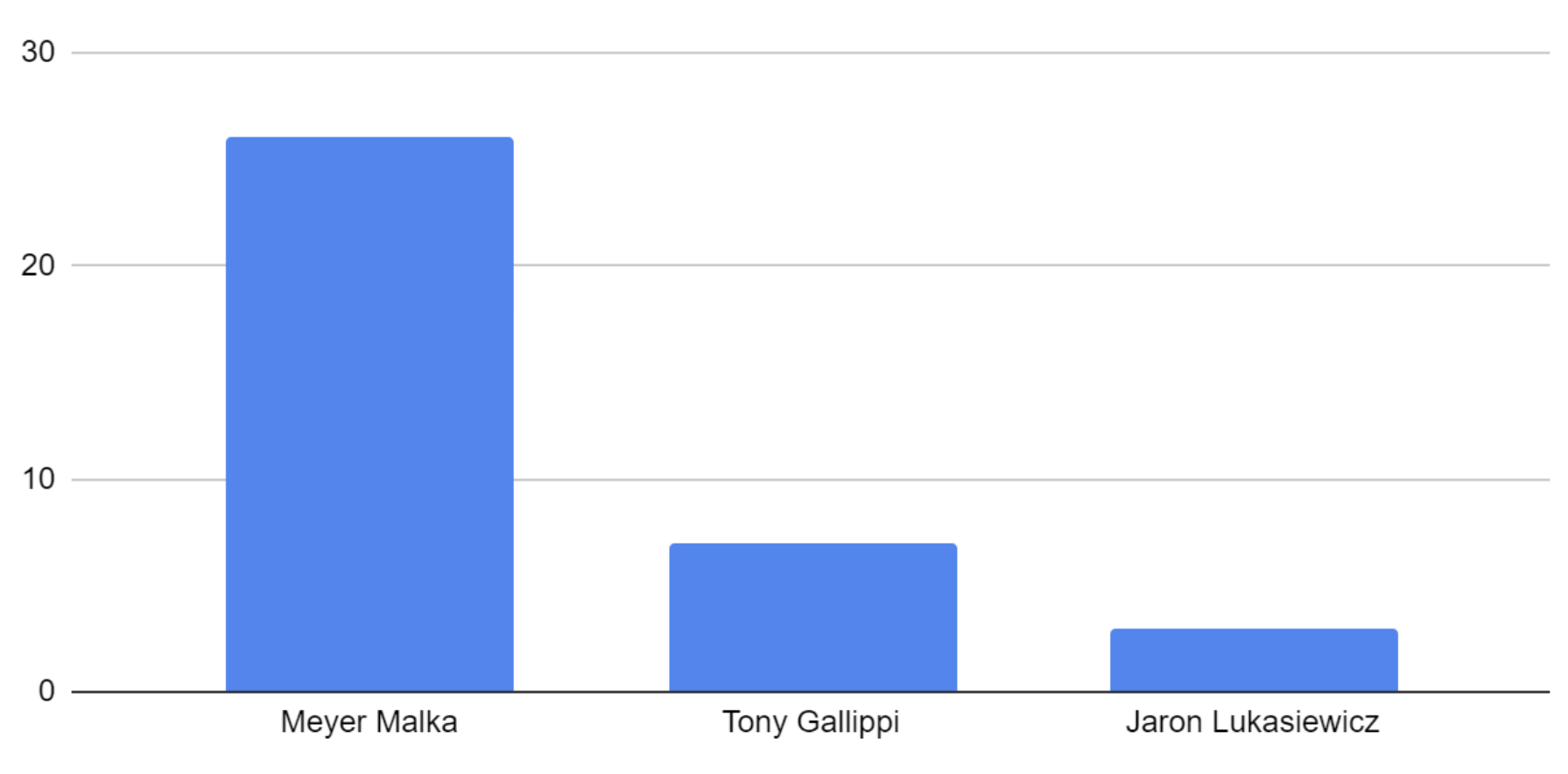

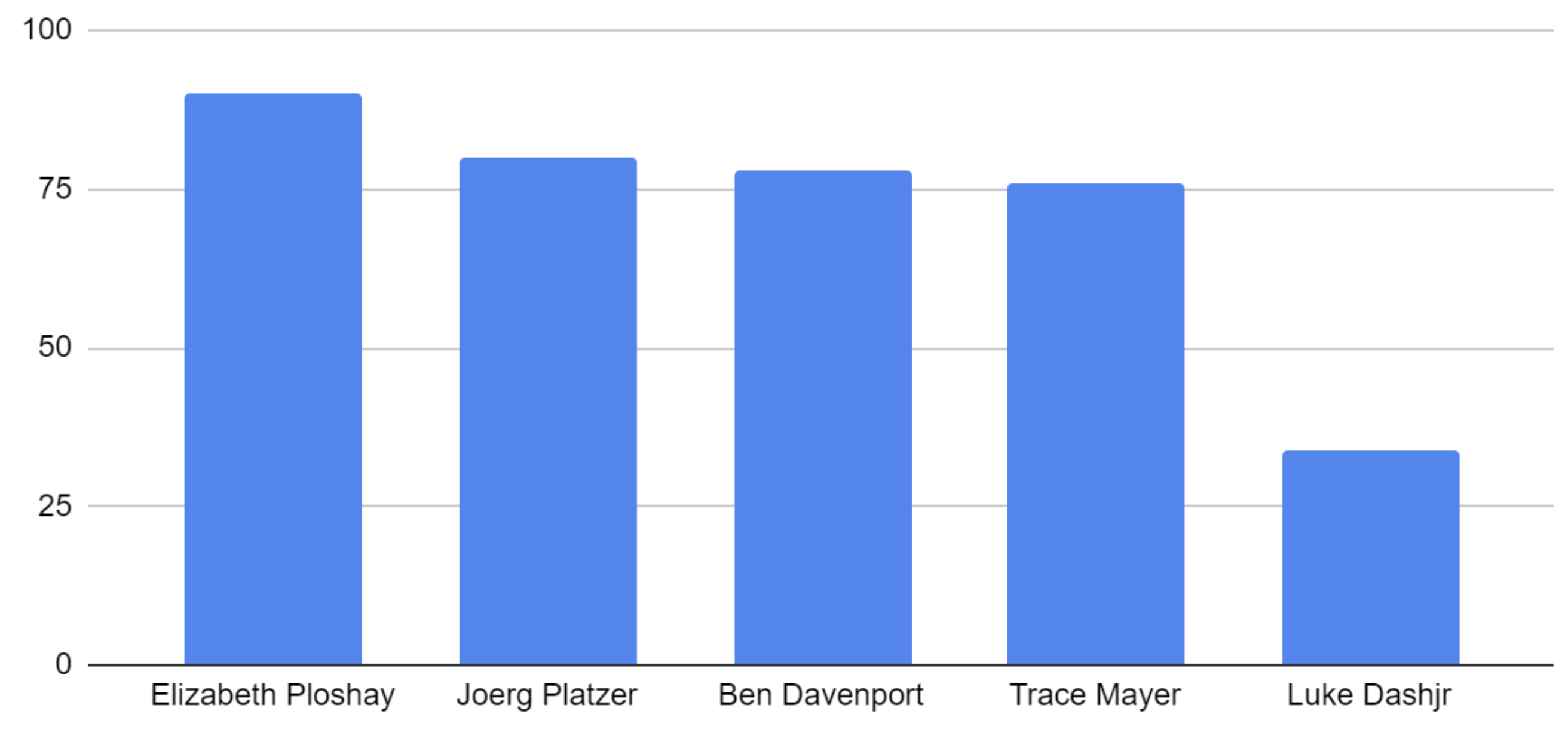

The first board elections took place in 2013, with Meyer Malka winning the Industry seat and Elizabeth Ploshay winning the vote amongst individual members.

Board Election – Industry Seat (2013) – Winners: Meyer Malka

(Source: Bitcoin Foundation)

Board Election – Individual Seat (2013) – Winner: Elizabeth Ploshay

(Source: Bitcoin Foundation)

At the start of 2014, the holders of the two founding industry seats resigned. Charles Shrem resigned on 28 January 2014, two days after his arrest at JFK airport for money laundering and unlicensed money transmitter related offences. Charlie was eventually convicted and sentenced to two years in prison in December 2014. The main substance of Mr Shrem’s felony appears to be that he continued to provide customer support to a user of his BitInstant Bitcoin purchasing service, despite him allegedly knowing the customer wanted Bitcoin for the purposes of purchasing illegal drugs on the Silk Road e-commerce platform (Or that the customer wanted to supply the Bitcoin to somebody else, who wanted to purchase illegal drugs, one extra layer removed). Mark Karpeles, the holder of the other industry seat, resigned on 24 February 2014, following the failure and insolvency of the MtGox Bitcoin exchange, where Mark was CEO.

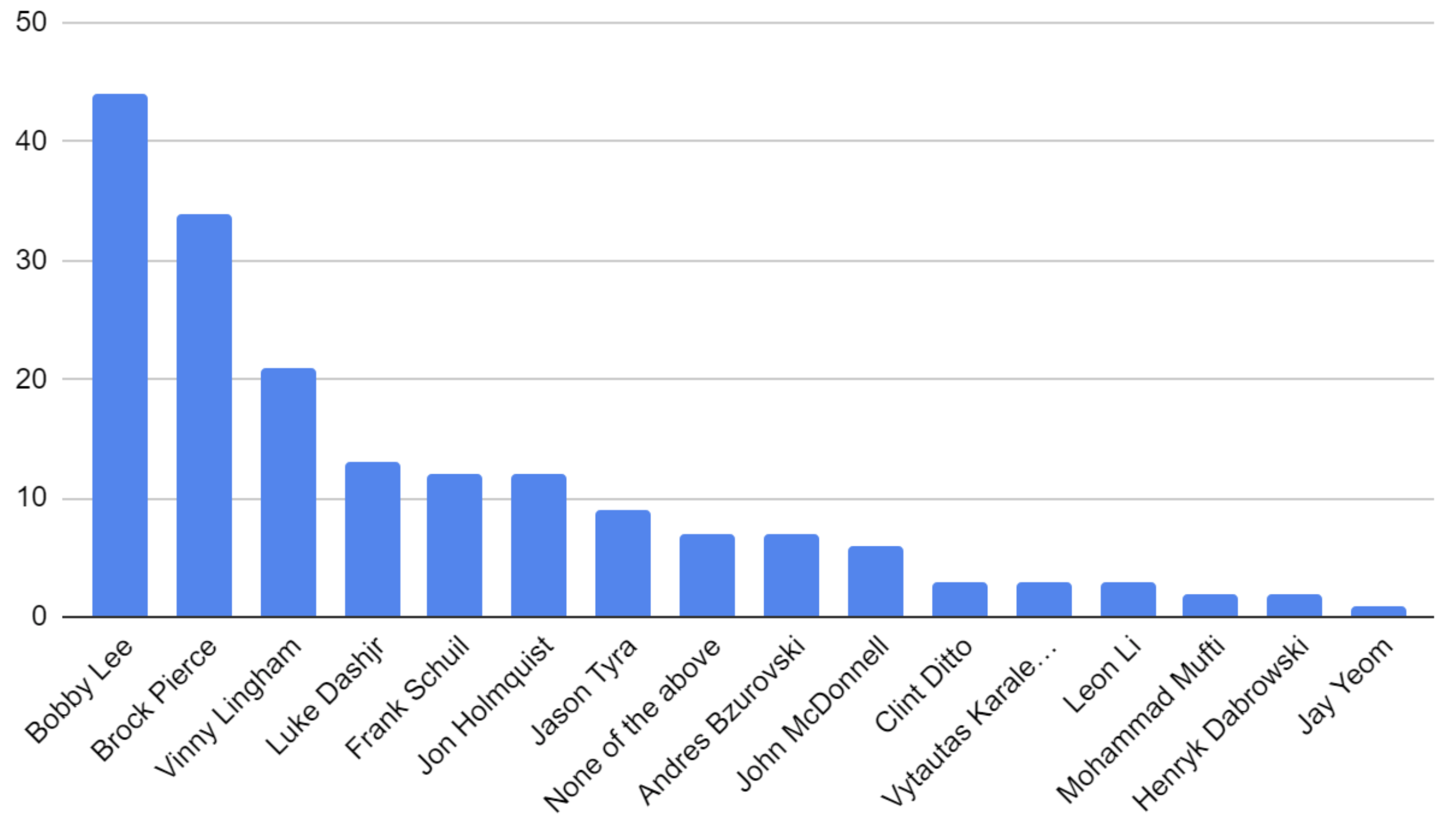

Brock Pierce and Bobby Lee were then elected as the two replacement industry appointed board members.

Board Election – Industry Seats (2014) – Winners: Bobby Lee & Brock Pierce

(Source: Bitcoin Foundation)

The appointment of Brock Pierce to the board proved controversial, with some claiming the Foundation should have done more vetting before allowing Mr Pierce to stand. The allegation against the former child actor, who featured in the “Mighty Ducks” and Disney’s “First Kid” was related to his alleged involvement in the sexual exploitation of children in the late 1990s. Although only a teenager at the time, Mr Pierce was an executive and co-founder at the internet video startup, Digital Entertainment Network (DEN), which was accused of hosting several parties where sexual abuse may have taken place. The allegations resulted in co-founder and CEO Marc Collins-Rector, along with Mr Pierce, resigning from DEN and supposedly fleeing to Spain. Mr Collins-Rector eventually plead guilty to child abuse related offences and according to Reuters, court record show that Mr Pierce paid US$21,000 to settle a related civil suit, while other claims were dropped, the article also states that Mr Pierce denies the allegations.

Towards the end of 2014, in the face of considerable pressure, the Foundation made the following improvements to its governance:

- Board member terms were reduced to 2 from 3 years

- The founder board seat was eliminated

- The founder member class was removed

The Foundation’s Finances

The below table provides a basic analysis of the Foundation’s finances, in the period where most of the member dues were depleted (2012 to 2014). The data is based on the organisation’s IRS990 forms. With respect to the pay of the board, the disclosure seems reasonably strong. Most board members received no remuneration other than those acting as executives. Paying Gavin was one of the main aims of the organisation and Gavin’s pay appears to be disclosed in a reasonably clear and appropriate manner.

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Directors pay | |||

| Gavin Andresen | $15,000 | $209,648 | $147,917 |

| Patrick Murck | $57,592 | $115,001 | |

| Lindsay Holland | $160,652 | ||

| Jodie Brady | $141,667 | ||

| Jon Matonis (Contractor) | $31,250 | $137,500 | |

| Other pay costs | $14,013 | $118,047 | $582,782 |

| Total pay costs | $29,013 | $577,189 | $1,124,867 |

| Conference costs | $418,413 | $825,525 | |

| Other costs | $32,608 | $472,302 | $1,335,210 |

| Total costs | $61,621 | $1,467,904 | $3,285,602 |

| Foundation Revenue | |||

| Membership fees | $358,007 | $335,723 | |

| Conference revenue | $377,883 | $584,308 | |

| Other | $64,803 | $35,728 | |

| Total revenue | $159,359 | $800,693 | $955,759 |

| Surplus/(Deficit) | $97,738 | ($667,211) | ($2,329,843) |

| Disclosed Bitcoin figures | |||

| Bitcoin (US$ value at year end) | $107,549 | $4,512,316 | $703,843 |

| BTC sales proceeds | $749,157 | $569,728 | |

| Realised Bitcoin gains/(losses) | $77,148 | ($40,316) | |

| Unrealised Bitcoin gains/(losses) | $5,195,589 | ($1,966,768) |

(Source: IRS 990 Forms, BitMEX Research)

The main criticisms related to the Foundation’s finances at the time appear twofold:

- There was a sharp increase in spend in 2014, depleting the organisation’s reserves to near zero

- There was a lack of transparency with regards to the Foundation’s Bitcoin balance

As for the first criticism, concerns did seem somewhat justified. In 2014 pay costs increased by 81%, the 2014 conference made a significant net loss and other costs increased significantly. As for the $1.3m in other costs, we have provided a breakdown below, therefore readers can judge the extent of the excesses. Compared to the excesses of the ICO bubble in 2017/18, where the total sum of the costs below perhaps represent a fraction of just one marketing party for the most egregious ICOs, the spend is moderate. However, some Foundation members clearly expected their funds to be spent more prudently. The main issue appears to be that expectations were not clearly set out in advance. Whatever your view, the fact is that by the start of 2015, the Foundation had almost run out of financial reserves and to that extent, its finances were mismanaged.

2014 breakdown of other spend

| Other professional services | $307,767 |

| Legal fees | $200,003 |

| Travel | $159,166 |

| Information technology | $158,021 |

| Professional event expenses | $115,401 |

| Public relations | $93,241 |

| Exchange loss | $73,362 |

| Accounting | $50,556 |

| Office costs | $39,071 |

| Grants (Foreign) | $37,314 |

| Bad debts | $18,500 |

| Payments to affiliates | $18,002 |

| Occupancy | $17,949 |

| Grants | $14,000 |

| Advertising | $9,218 |

| Insurance | $3,639 |

| Other | $20,000 |

| Total other spend | $1,335,210 |

(Source: Bitcoin Foundation IRS 990 form)

The lack of transparency with respect to the Foundation’s Bitcoin balance is another area of concern. At the end of each year the IRS990 form disclosed the USD value of the Bitcoin holding, the realised Bitcoin gains and the unrealised Bitcoin gains. Based on this information we calculated the following:

| BitMEX Research BTC calculations | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

| Bitcoin price at year end | $13 | $754 | $320 |

| Implied BTC balance at year end | 8,216 | 5,985 | 1,381 |

| Change in BTC balance | (2,232) | (4,604) | |

| Implied sales price | $336 | $124 | |

| Realised Bitcoin gains/(losses) | $719,945 | ($2,901,314) | |

| Unrealised BTC gains/(losses) | $4,433,979 | ($599,354) | |

| Lowest Bitcoin price figures | |||

| Lowest Bitcoin price in the year | $4 | $13 | $268 |

| Implied BTC sales proceeds | $29,011 | $1,233,739 | |

| Realised Bitcoin gains/(losses) | ($201) | ($2,237,303) |

(Source: IRS 990 Forms, BitMEX Research)

The disclosures in the IRS990 forms lead us to the following apparent Bitcoin related discrepancies:

- The Foundations closing bitcoin balance in 2012 seems reasonably low given the volume of Bitcoin donations (See the c.28,000 BTC figure earlier in this report)

- The Foundation disclosed an unrealised Bitcoin gain in 2013 of $5.2m, however based on the annual price movement and the calculated year end balance, we calculated an unrealised gain of only $4.4m

- The Foundation disclosed an unrealised Bitcoin loss in 2014 of $2.0m, however based on the annual price movement and the calculated year end balance, we calculated an unrealised loss of only $0.6m

- The Foundation disclosed Bitcoin sales proceeds of $569,728 in 2014, while even assuming all Bitcoin were sold at the lowest traded price in the year, given the large reduction in the Bitcoin balance of 4,600 coins, sales proceeds should have been $1.2m

Although there were accusations of embezzlement, we do not consider these disclosures to indicate any such crime. The Foundation was probably receiving Bitcoin and spending Bitcoin throughout the period, therefore clear financial record of Bitcoin sales are not likely to be available. At the same time, rules related to the reporting of realised and unrealised gains with respect to financial assets are not strict for this type of organisation and the Foundation does have a degree of discretion with respect to the calculation methodology. Therefore, the filings themselves do not indicate wrongdoing in our view. However, what we can say is that filings do not clearly explain what happened to the Bitcoin balance and an explanation from the board could be helpful.

Some members clearly expected greater transparency and wanted to question the board about the funds, but they were never given such an opportunity. The following quote from Bitcoin commentator Andreas Antonpoulous (who at the time was a Foundation committee chairman), reflected the views of many in the community at the time.

You say they are funded. Where are those funds? Who controls those funds? When were the last audited? Are they actually solvent? Or have all of those funds disappeared into a big black hole? Just remember who was in the leadership until recently, who is in the leadership today and what their track record of ethics has been and I would suggest that I would not be surprised at all if the Foundation implodes in a giant embezzlement problem sometime down the line or funds get stolen, within quotes or without quotes, or something like that. It’s bound to happen because these things don’t happen due to technical failures of bad actors, they happen due to failures of leadership The Foundation is the very definition of a failure of leadership.

(Source: Andreas Antonopoulos – March 2014 – Let’s Talk Bitcoin Episode 95)

Entanglement in the MtGox Scandal

To make matters worse, there were also accusations of the Foundation’s entanglement in the MtGox insolvency:

- The MtGoX CEO, Mark Karpeles, was a founder and founding board member of the Foundation, while the company itself was a platinum member of the Foundation

- Founding member, Roger Ver, famously assured MtGox customers of the solvency of the platform shortly before the exchange failed

- The Foundation’s founding chairman, Peter Vessenes (who may have believed he was entitled to some MtGox equity), has been involved in various legal disputes with MtGox dating back to 2013 as a result of a failed business partnership. Peter’s company Coinlab sued MtGox for US$75m in 2013. As of August 2019, Peter now claims a remarkable total of US$16bn (Y1.6 trillion) from MtGox, an amount large enough to effectively block distributions to MtGox clients, and a large source of frustration to creditors to this day.

Andreas compared the Foundation’s situation to MtGox as follows:

Its problems go directly back to a complete failure of leadership. A completely closed, insular, arrogant, sheltered, uncommunicative leadership. Part of which was Karpeles himself, but there are another couple of relics left on that board, who pursue the exact same approach with their leadership. The Foundation is the Gox of Foundations. I am surprised it didn’t blow up in the wake of the Gox scandal, because there were a lot of significant conflicts within that environment.

However, perhaps it is unfair to make much of the association between MtGox and the Foundation, afterall, the ecosystem was small and MtGox was the dominant exchange, therefore a degree of association was inevitable to some extent.

The Amsterdam Conference (May 2014)

In May 2014 the Bitcoin Foundation arranged what was, up until this point, the largest conference in the space. It was the first conference (at least one which we attended), with characteristics familiar to many in the 2017/18 era. Unabated enthusiasm, unrealistic expectations about the underlying technology, expensive catering and countless booths representing new businesses with plans that appeared to make little commercial sense. As the figures above indicate, despite the expensive ticket prices of up to $800, the conference appears to have generated a net loss of around US$250,000.

The conference was split into two sections, a commercial section in the main exhibition hall, and the Bitcoin Foundation annual meeting (or technical track), which was down the hallway in a hotel conference room, entry to which was free for Foundation members. The technical discussions were followed by the Foundation members’ meeting

(Source: Eventbrite)

Journalist Ryan Selkis (now founder & CEO of Messari), was one of the key lifetime members at the event trying to hold the Foundation to account. At the annual meeting he asked several challenging questions to the Foundation board members, asking for greater transparency. Up until this point much of the debate and complaints had taken place on online web forums and this real world interaction marked a significant and novel change. In response to his challenges, one board member said the following:

We can spend a lot of our time trying to be transparent as much as we can and higher resources can be transparent or we can spend a lot of time in the board level making sure that we [have the] resources to make bitcoin bigger. It’s possible but right now, honestly, we’re in an environment where bitcoin is not well perceived. You asked for priorities at least from my side as a board member, it’s more about [making bitcoin bigger]

(Source: Bitcoin Foundation 2014 Annual Meeting)

It was clear from this response that, for whatever reason, some board members had chosen not to tackle the transparency and governance concerns, leaving some members feeling frustrated and more convinced of wrongdoing on the part of the board.

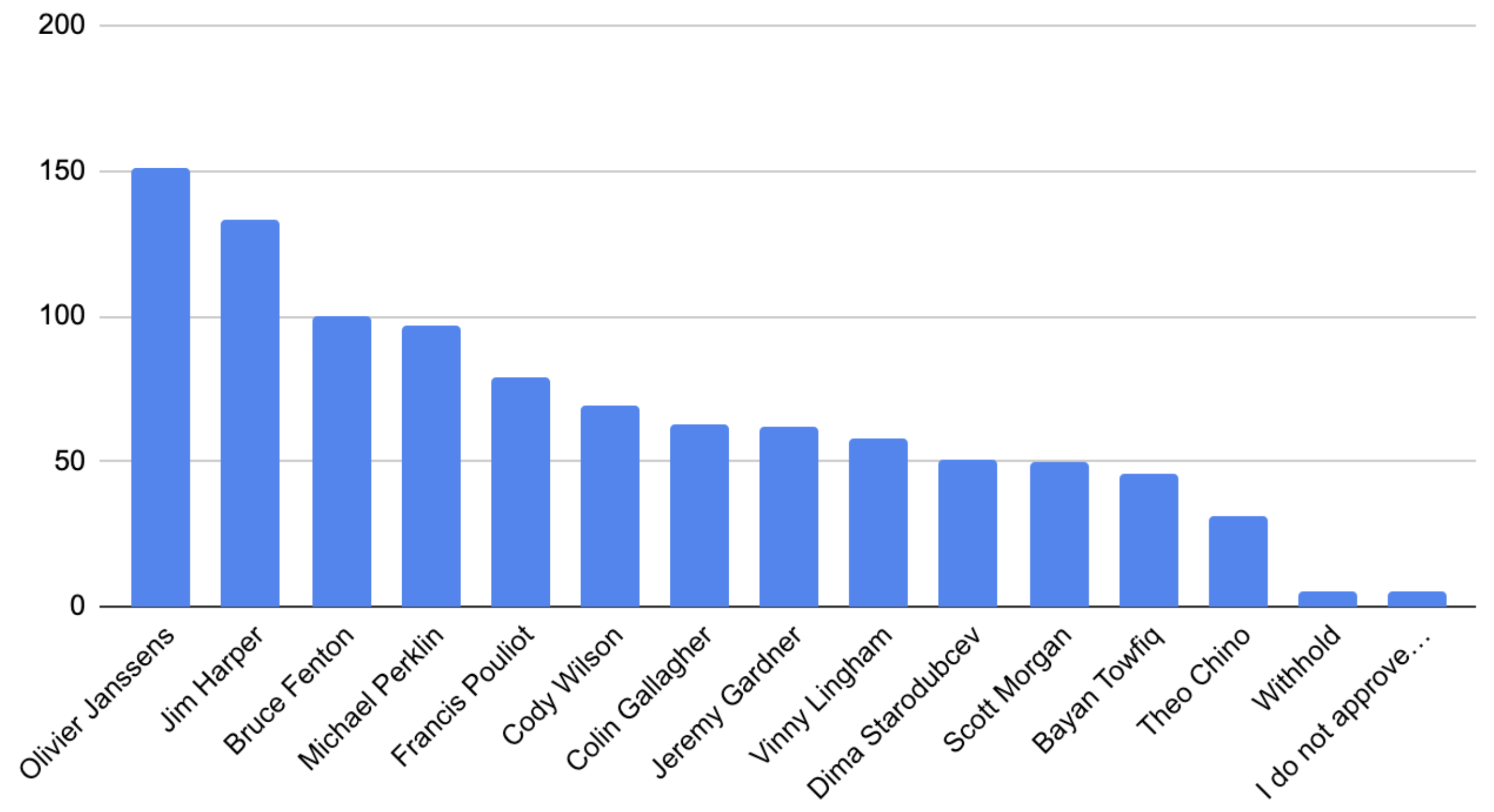

The Blockchain Election (February 2015)

Given the issues that the Foundation had faced and the concerns in the community about transparency, governance and the purpose of the Foundation, this was a relatively important set of elections. There was a large number of candidates and a reasonably good quality debate among the candidates, for example a dedicated Let’s Talk Bitcoin podcast on the election.

The Foundation decided to conduct the 2015 individual board seat elections on the blockchain. As the chair of the election committee, Brian Goss said:

I believe in the concept of using the block chain for storage of compact proofs/hashes (as the market dictates), and I’m a big believer in transparent voting that any one can verify

(Source: Bitcoin Foundation Forum)

However, the blockchain voting process did not run smoothly and the following issues arose:

- The first round of voting took place using the Helios voting system. However, no candidate achieved more than 50% of the vote, as required by the by-laws, therefore a second round was required. The Foundation then made the odd decision to switch the voting platform to Swarm between the voting rounds, a decision met with widespread opposition. Despite initially starting the final round voting process on Swarm, during voting the Foundation then decided to switch back to Helios, invalidating the Swarm votes

- The decision to reduce the number of candidates to four after the first round of voting appeared arbitrary

- Registering to vote was widely regarded as a cumbersome and complex process and some candidates complained

(Source: Email received as part of the Swarm voting process)

Board Election – Individual Seats First Round (2015)

(Source: Helios voting system records)

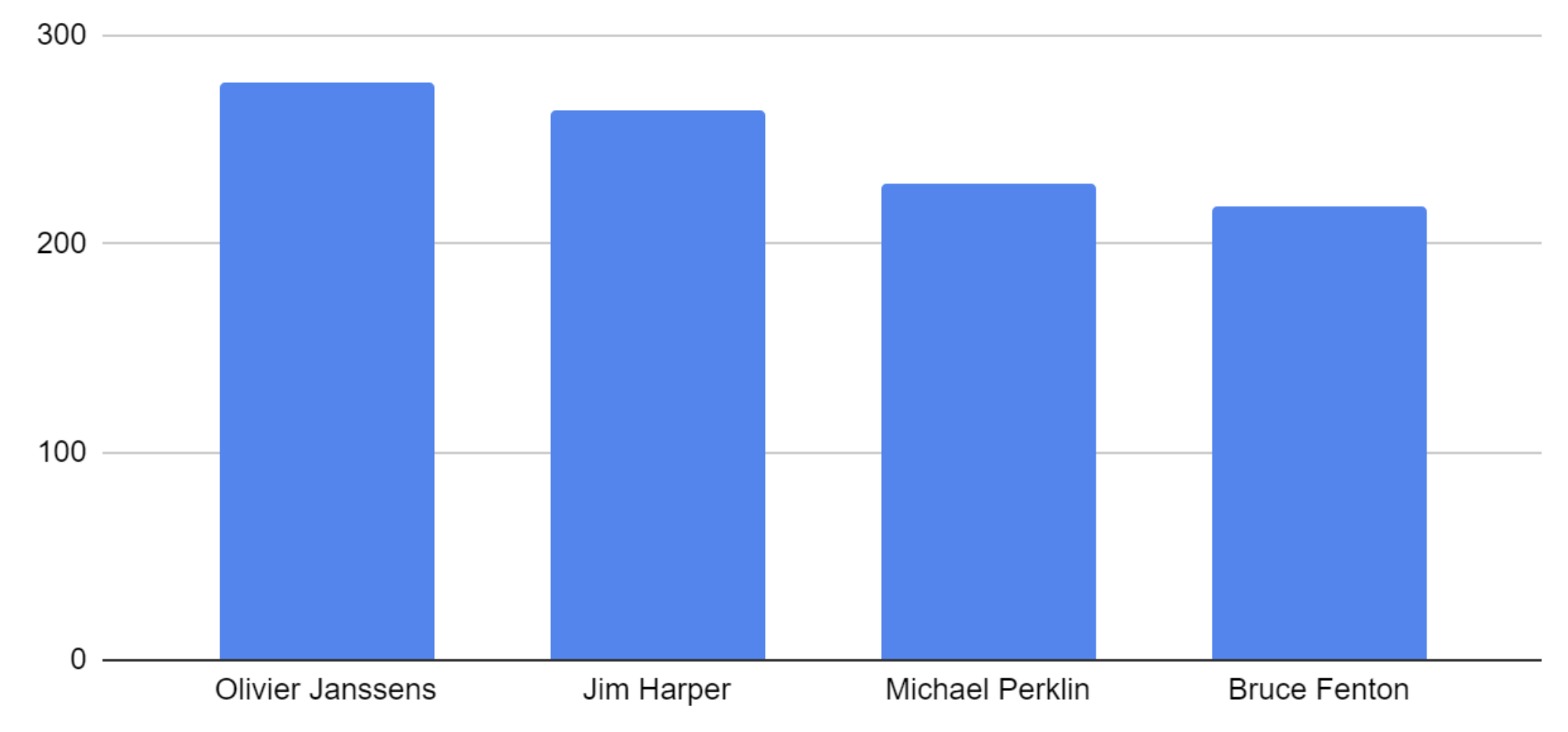

Board Election – Individual Seats Final Round (2015) – Winners: Oliver Janssens & Jim Harper

(Source: Bitcoin Foundation)

After the voting controversy, Patrick Murk told Bitcoin Magazine:

This clearly struck a nerve with folks that think blockchain technology should only be used for transferring Bitcoin and not other [applications] like voting. [It] sparked a debate on how people use the blockchain

(Source: Bitcoin Magazine)

Removal of Directors & The End Of Board Elections (December 2015)

In December 2015, the two newly elected board members, Oliver and Jim, were removed by the other board members, due to a disagreement over the best way forward for the Foundation. Oliver and Jim had recently succeeded in competitive elections from individual members, giving them a considerable democratic mandate. At the same time the two year election terms of Elizabeth and Meyer had already expired, while Brock and Bobby had been elected by the industry and not individuals. Therefore, from the point of view of the individual members, Oliver and Jim were the only two board members with a significant mandate and they had been removed. In a violation of the by-laws, the Foundation then decided not to conduct any further board elections. As the executive director Bruce Fenton put it:

I used to believe that public, open elections were a great thing. I’m not as convinced now…. We unfortunately don’t have the time or resources for more process.

(Source: Bitcoin Foundation forum)

In our view, this logic seemed difficult to justify, given many of the problems were caused by the boards apparent lack of accountability to individual members, with Elizabeth Ploshey being the only board member elected by individual members who served on the board for any meaningful amount of time. If the Foundation did want to revive itself, it could have reinstated Oliver and Jim and allowed further elections to replace the other board members who could have left. Instead, the Foundation decided to distance itself even further from members, avoiding the challenges this accountability would have imposed, and consequently the Foundation appeared to lose any remaining legitimacy it had left.

After this point, between 2015 and 2019, four new board members were appointed from the pool of candidates that were defeated in the previous elections, except this time appointments were made by the board rather than members.

Conclusion

The Foundation still exists today, with Brock as Chairman and Bobby as Vice chairman, although their elected terms have long since expired and no more elections are in sight. The Foundation has no significant financial resources and is largely irrelevant. The activities the Foundation used to conduct are now carried out by others, for example Coin Center does some regulator lobbying, and Bitcoin development is funded by other organisations such as Chaincode Labs, Blockstream, MIT’s DCI and other industry players. In many ways the conclusion to this piece writes itself. Bitcoin never needed a Foundation, it is stronger without one, and any all-encompassing Foundation like this was always doomed to fail.

The outrage at the lack of transparency at the Foundation exposes some of the key divergences in expectations and culture between members of the Bitcoin (now cryptocurrency) community. Some Bitcoiners, especially those involved since the early days of the Foundation, were often highly conspiratorial, paranoid and expected radically high levels of transparency, accountability and financial prudence. The Foundation seems to have misjudged these expectations, lost the backing of the community and ultimately failed. However, compared to the excesses of the coin offering era, which picked up from around 2014 onwards, peaking at the start of 2018, the financial accountability and transparency of the Bitcoin Foundation was almost impeccable, relatively speaking. Some members of the cryptocurrency community (not all newer ones), had radically different expectations, focusing more on what they perceived as game-changing technology, changing the world and getting super rich, rather than governance. Even in this new climate, irreparable damage to the Foundation’s brand had been done and it never again found its place.

UPDATE – 23 September 2019

After the publication of this piece, several prominent Bitcoin developers, whose names were displayed on the Foundation’s website, indicated to us (in some cases with proof) that they were given membership status for free (rather than by paying 25BTC). This may indicate that:

- Support for the foundation may not have been as widespread as we initially thought

- The Foundation’s bitcoin balance in 2012 may never have been as large as we initially thought