We’ve had a number of questions from our traders over the past week about the role and performance of the Insurance Fund on 12 and 13 March. In this update, we explain more about how the Fund works, and what it’s used for. We also address questions including how we calculate an appropriate size for the Fund, and why it grew during this period.

What does the Insurance Fund do?

Before we begin, and now that the markets have settled, it’s important to put the role of the Insurance Fund into some context. For both the traditional and cryptocurrency markets, the 12 and 13 March brought unprecedented volatility. During these events, the Fund acted as the last line of defence, by attempting to prevent Auto Deleveraging (ADL). ADL means the automatic deleveraging of the positions of profitable traders (ranked by profit and leverage in that contract) against liquidated positions to prevent bankruptcy.

This is different from a traditional exchange, on which traders can lose more than the margin posted in their account. If this happens, the exchange collects any losses owed, with the clearing house and its members taking all the credit risk. Here is one example from Europe in 2018 showing what can go wrong with this.

By contrast, on BitMEX, losing traders never owe more than the margin posted. The Insurance Fund provides an assurance that, despite this limited downside for losing traders, the upside is not limited either, and profitable traders are likely to receive their expected profits.

So what doesn’t it do?

- It does not cover BitMEX running costs or contribute to BitMEX profits

- It does not demand payments from traders with negative account balances

- And it is not used to influence markets, intentionally or otherwise

The Insurance Fund exists to act as a last line of defence to prevent ADL. On 12 and 13 March, despite the extreme market movement ADL was completely prevented.

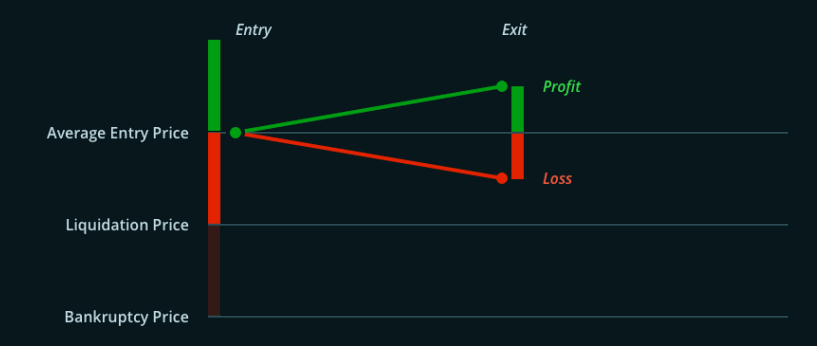

Chart One below shows a normal trade resulting in a profit or loss. For the purposes of this guide we will follow the loss, starting with the Bankruptcy Price.

Terms

It is important to understand the following terms:

- Bankruptcy Price: The price at which a position has zero equity left (all posted margin has been depleted)

- Liquidation Price: The price at which a position has a small amount of equity left (only Maintenance Margin remains). At this point, the Liquidation Engine will take over the position

Trading at 100x long on XBTUSD:

| Entry Price | Liquidation Price | Bankruptcy Price |

| 6,000 | 5,970 | 5,940 |

Bankruptcy Price

A trader places an order, executes trades and posts margin against their positions and then is able to reallocate their margin. Based on the allocated margin, each position has a calculated Bankruptcy Price. This is the price at which the unrealised loss on a position (calculated using the Mark Price) is equal to all of the margin posted.

If a trader buys XBTUSD at 6,000 using 100x leverage, the Initial Margin required is 1% of the total value and the trader’s position will be bankrupt if the price falls by 1% to 5,940. This is the Bankruptcy Price.

An exchange must remain solvent for its traders’ profits and positions to remain secure. In this case, the position needs to be closed out at or better than the Bankruptcy Price. However, due to changing market conditions, execution at a favourable price cannot be guaranteed – even for the smallest position – because there may not be a bid/offer matching the price and size required.

In the example above, imagine the position was finally closed at 5,900. This would create a loss which is more than the margin the trader posted. In traditional markets, the exchange would actually request more money from the participant and mark a credit risk against them if they couldn’t pay.

Liquidation Price

To protect against those losses that a trader would receive from closing out at the Bankruptcy Price, the trader also posts a Maintenance Margin (which is included in the margin allocation). The Liquidation Price is the price at which the difference between the unrealised loss and the margin posted is equal to the Maintenance Margin.

For the trader who buys XBTUSD at 6,000 (with a Bankruptcy Price of 5,940), the Maintenance Margin required is 0.50%. If the price were to fall instead to 5,970, the remaining margin would be equal to the Maintenance Margin.

When the Mark Price breaches the Liquidation Price, the trader’s position is liquidated and their Maintenance Margin is taken over by BitMEX’s Liquidation Engine.

Liquidation Engine

We should note here that the Liquidation Engine attempts to prevent liquidation, if possible. It will do this by attempting to reduce the Maintenance Margin requirement by cancelling orders before liquidation can occur. And, for larger positions, this can bring traders to a lower Risk Limit (a partial liquidation).

The BitMEX exchange aggregates liquidated positions, by posting the margin drawn from the Insurance Fund. It is here where the Liquidation Engine is programmed to trade each contract according to five criteria. These are as follows:

- Reduce Only: Trades executed by the Liquidation Engine can only reduce the gross positions acquired from liquidations

- Best Price: Trades should reduce/exit the aggregated liquidated position at the best possible price (highest for longs, lowest for shorts), in order to preserve the fund size

- Limited Balance: The unrealised loss should not be more than the balance made available for that contract from the Insurance Fund (ADL should be avoided)

- Fast Execution: Trades should exit the aggregated liquidated position as quickly as possible to reduce the risk of adverse price movements while exiting the position

- Limited Impact: Trades should attempt to minimise market impact

Any trader can tell you that to satisfy only one of these criteria will often be trivial, but satisfying all of them poses a complex optimisation problem, involving many external factors. The success of these criteria depend greatly on the actions of other traders.

For example, imagine what would happen to the price of gold (5. “Limited Impact”) if the Federal Reserve tried selling all of its gold in one go (4. “Fast Execution”) at the current market price (2. “Best Price”). Instead, the Liquidation Engine’s trading program parameters adjust to these external factors to balance these criteria.

The job of the Liquidation Engine becomes easier when liquidity is deep, trading is range-bound, price moves are slow, and the order book replenishes quickly. But this job becomes more difficult when trading is directional, the price moves are fast, liquidity is thin, and the order book replenishes slowly.

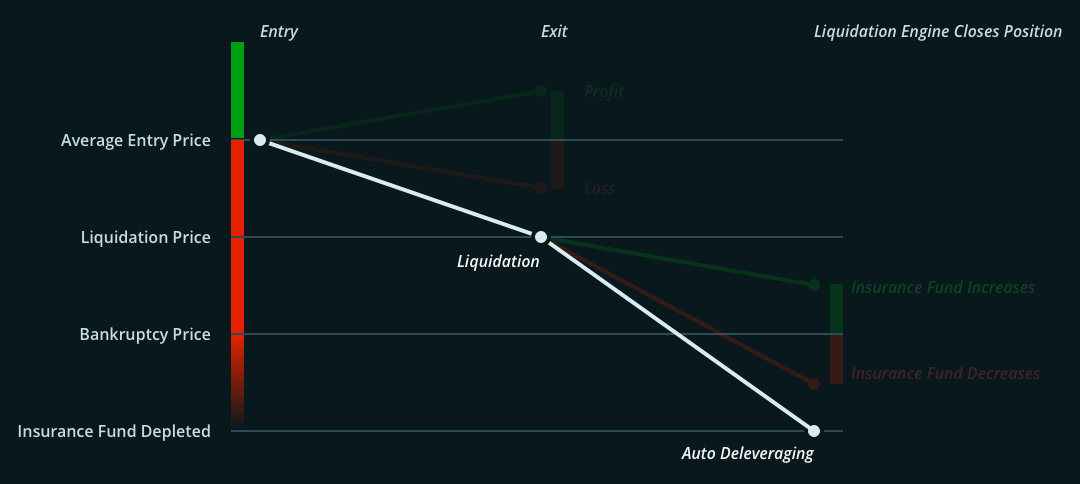

The Last Line of Defence

The Liquidation Engine can’t satisfy all of these trading criteria in difficult conditions and it will make a loss, but it can outperform in easier conditions to offset this.

Let’s say the trader above is liquidated at 5,970. The Liquidation Engine takes over the position and is now long 100 contracts of XBTUSD at the Bankruptcy Price of 5,940.

The Liquidation Engine manages to sell its position in the market at an average price of 5,900. It has lost $40 per contract and draws from the Insurance Fund to avoid going bankrupt. But in some circumstances, the Liquidation Engine can close its position out at a profit.

Let’s imagine it sells into a slow-moving market and unwinds the position at an average price of 5,955, making $15 per contract. It is here where that profit is added to the Insurance Fund, providing funds for future liquidations to draw against, as shown in the chart below.

The Insurance Fund is the margin available to the Liquidation Engine to close out its positions. When the Liquidation Engine’s unrealised loss on a given contract is larger than the Insurance Fund balance allocated to that contract, the Liquidation Engine reaches its own Bankruptcy Price and can no longer trade. At this point, the only mechanism left to protect the integrity of the market is ADL. The successful traders, ranked by profitability and leverage, are then force-closed out of their positions against the Liquidation Engine.

The larger the Insurance Fund balance and the smaller the position in the Liquidation Engine, the further the Bankruptcy Price of the Liquidation Engine will be from the price at which it acquires the position, meaning less chance of ADL. The Insurance Fund provides a buffer between our traders and ADL. The larger it is, the less likely ADL will occur.

How does BitMEX calculate the appropriate size for the Insurance Fund?

We rely on three estimations to calculate what size the Fund should be:

- The Open Interest and historical volatility

- The liquidation and bankruptcy prices of open positions

- The cost of exiting the positions in different market conditions

We have a team at BitMEX which analyses historical data, models extreme price moves, experiments with variations in Maintenance Margin, estimates future Open Interest, and the changes in the shape, depth and behaviour of the order book. Effectively, it is their job to predict the unpredictable. As in any engineering project, we build on the side of caution because we want the Insurance Fund to be able to cover the projected worst-case day several times in a row.

The 12 and 13 March are useful as a proxy for one single worst-case day, with prices dropping from $8,000 to $4,000 inside a single day. While this did not deplete the Fund (see Charts Four and Five below for the exact performance), liquidity dropped significantly during the move. If a second move had taken place the next day, the Fund would have been stretched to its limits, but would likely survive due to its size and the trader confidence it creates. No other fund in the crypto ecosystem has the size to survive such an event. In this scenario, it is likely that massive loss-recovery events will take place at all other major crypto derivatives platforms.

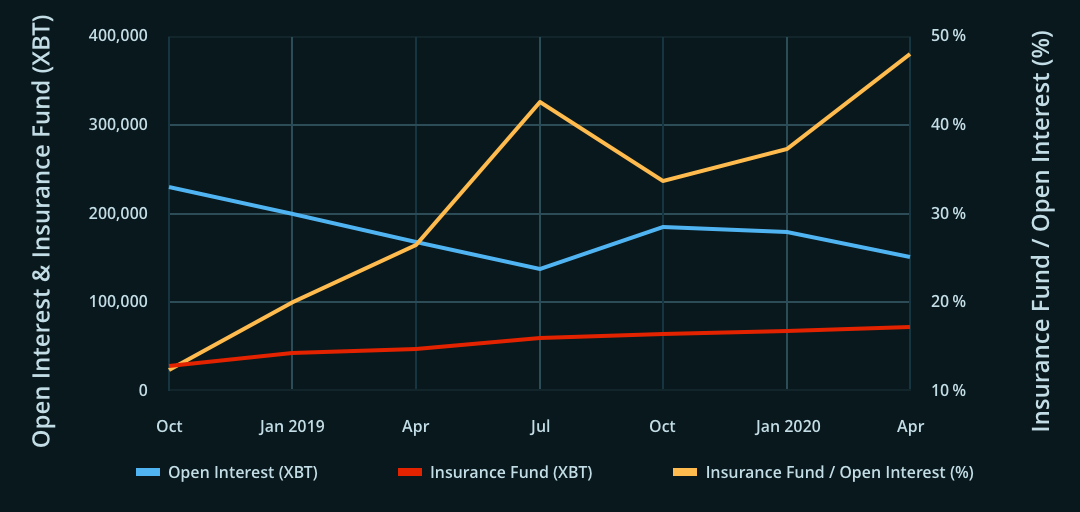

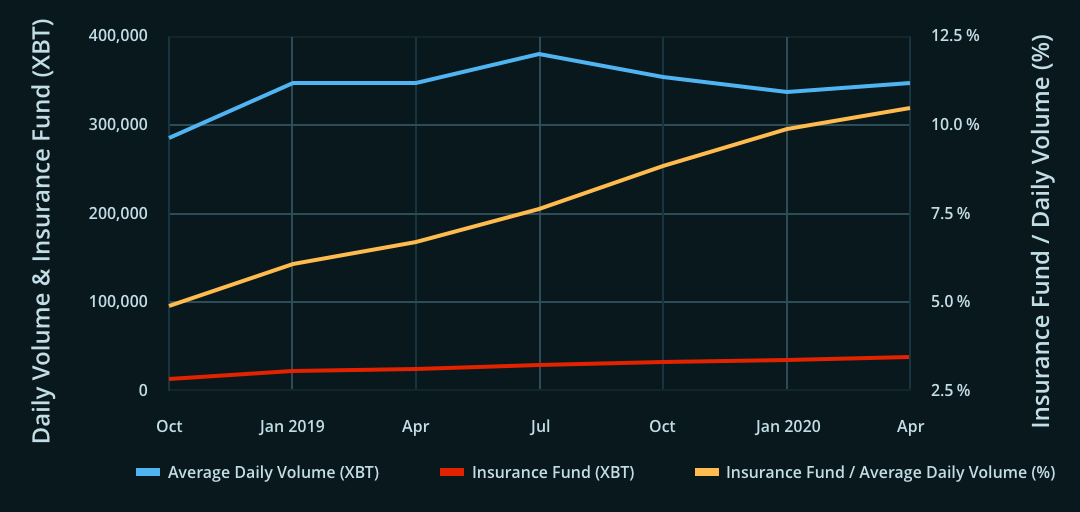

The Insurance Fund is denominated in XBT, like all balances on the platform, and it has grown gradually over the last 18 months. It now stands at around 34,678 XBT (as of 19 March 2020 daily snapshot). Since October 2018, the Insurance Fund balance has risen as a proportion of Open Interest, from 12% to 47%, and Average Daily Volume (“ADV”), from 5% to 10%.

|

|

| Fig. 4. BitMEX Insurance Fund vs Open Interest | Fig. 5. BitMEX Insurance Fund vs ADV |

The growth trajectory has continued in 2020, see Chart Six, with drawdowns on 19 January and 13 March.

|

|

| Fig. 6. BitMEX Insurance Fund Balance in 2020 (note that scale has been adjusted) | Fig. 7. BitMEX Insurance Fund Balance 11-14 March 2020 (date stamps 00:00 UTC) |

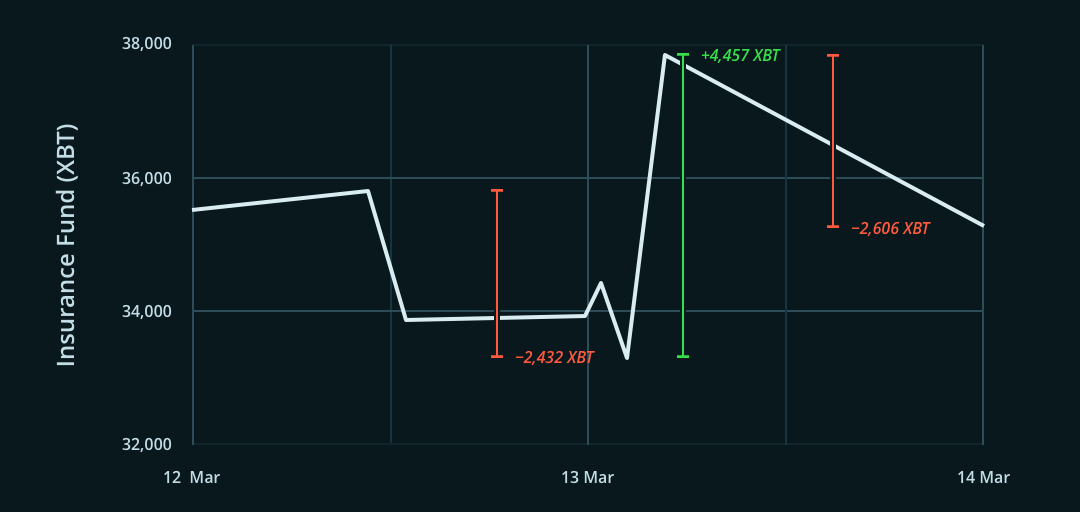

Chart Seven shows the intraday balance of the Insurance Fund. A snapshot is published daily at 13:01 UTC.

On normal trading days, the Insurance Fund should be on a growth trajectory. This ensures that when the Liquidation Engine faces extremely difficult conditions, there is enough reserve available to exit all the liquidated positions without causing ADL.

Having a robust and healthy Insurance Fund is critical. We publish our daily Insurance Fund total as a data point, but what matters most is not where the Insurance Fund ends up at the end of the day, but its lowest point. If an Insurance Fund allocation ever hits zero, ADL will take effect for that contract and force successful traders to reduce their positions. As we mentioned, ADL is highly undesirable. Since many traders run strategies across products and across exchanges, a forced exit can be an extremely costly situation and we seek to avoid it whenever possible.

How did the Liquidation Engine and Insurance Fund perform on 12 and 13 March?

The market movements of 12 and 13 March were extreme. There was a high volume of liquidations, which gave the Liquidation Engine a large aggregated long position in XBTUSD to exit.

The trading algorithm unwound this position into the market at prices that became gradually more aggressive (lower) as the long position grew and its time holding the position progressed. During this time, the Liquidation Engine’s trading activity realised significant losses, crystallised as drawdowns from the Insurance Fund. The largest drawdown on 13 March was 2,606 XBT. During this period, the largest unrealised loss on liquidated positions not-yet-exited by the Liquidation Engine was 5,652 XBT.

Therefore, if the Liquidation Engine algorithm had chosen to close its outstanding position at the Mark Price, assuming sufficient liquidity (which was not instantly available), the largest total drawdown (from the peak balance on 12 March) would have been 8,482 XBT. As the Liquidation Engine exited some of its positions above its average entry price gradually, the Insurance Fund grew by 4,457 XBT. It reached a peak balance of 37,836 XBT before reducing by 2,606 XBT because of realised losses on subsequent exits later in the day.

As a last line of defence, the Insurance Fund balance is important because the larger the balance (and the smaller the position in the Liquidation Engine), the further away the Bankruptcy Price for the Liquidation Engine will be from the price at which it acquires its positions. It is important for the Fund to be large enough to absorb intraday shocks, to avoid ADL on the platform. The lowest balance reached by the Fund, not the EOD balance, is the most significant number for risk mitigation.

The feedback that we get from the BitMEX community is incredibly important to us and we hope this explanation of the role of the Insurance Fund and how it performed during the events of 12 and 13 March is helpful. As always, you can contact support if you have any further questions.

And if you’d like to read more, you may also wish to refer to our blog from February 2019, in which we explored why the Insurance Fund is needed and how it operates: