Abstract: We examine the short seven year history of decentralised exchanges (dexes), including the first significant iteration of the technology, Counterparty. We consider why these early attempts failed and how they evolved into the Uniswap protocol we have today, with its clever mechanism for inducing and managing liquidity. We explore Uniswap, its copycats and how it fits into the defi landscape. We conclude by arguing that most of the defi excitement is generated by unsustainable price bubbles and aggressive token issuance schedules, fuelling speculative demand. However, underneath this unsustainable speculative frenzy and layers of complex interrelated defi platforms, we believe there could be technology which could lead to something sustainable. Non-custodial, leveraged, quasi decentralised trading, is too compelling of a concept to ignore.

Introduction

As we mentioned back in our January 2019 piece, Atomic Swaps and Distributed Exchanges: The Inadvertent Call Option, a distributed exchange (dex) should be considered as one of the two holy grails of financial technology, alongside the somewhat interrelated concept of distributed stablecoins. To clarify our thinking, the purpose of an exchange or stablecoin being distributed is reasonably simple and concise, it is to ensure the system is unstoppable, in the face of regulatory pressure. Nobody should doubt the potentially transformational impact of these systems, even the most extreme skeptics, if they can indeed be made to work. A rational criticism of distributed exchanges may be that they cannot work in a robust way.

A dex is certainly technically possible, within the confines of a single blockchain ecosystem and the tokens which exist within that system. Since all the tokens are native to the blockchain, one can build an exchange, with a centralised order book and clearing mechanism on top of the blockchain. This can be done on Bitcoin (For example Counterparty) or Ethereum. The main challenges are scalability, liquidity, usability and ensuring the fairness of the exchange. This report will focus on these kinds of dexes, ones without cross-chain capabilities. Dexes which seek to enable the trading of assets on multiple blockchains or non cryptography based assets, such as the US Dollar is a separate topic (See Bisq).

Counterparty

Way back in 2013, what is widely regarded as the first ICO in the space occurred, Mastercoin. The aim of the project was to be a protocol to launch multiple tokens on top of Bitcoin. Essentially surplus Bitcoin transaction data was interpreted by the Mastercoin protocol, as issuing or spending additional tokens. A Mastercoin foundation was set up to manage the proceeds from the ICO. However, there was considerable pushback from the community about the foundation and the unfairness behind the idea that a select few would be given the privilege of managing and controlling the funds.

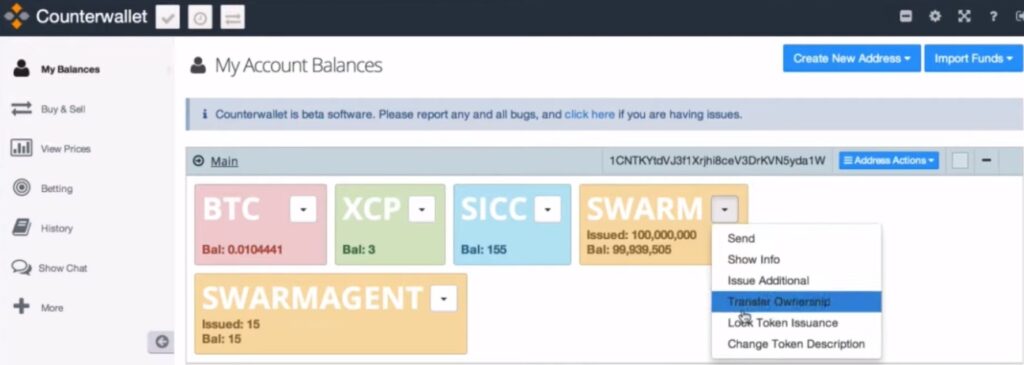

Therefore, towards the start of 2014, a rival project was set up, Counterparty. This had the same premise as Mastercoin and also had a token, XCP, compared to Mastercoin’s MSC. However, rather than having an ICO, where a select group would manage the funds, there was a “proof of burn”, where bitcoin were sent to a provably unspendable address and the initial XCP coin allocation was decided by who burnt the most bitcoin. This avoided the need for a controversial foundation. Due perhaps to this “fairer“ token launch, and the hard work of lead developer Adam Krellenstein, the Counterparty protocol succeeded in becoming the dominant token issuance platform in the space. The XCP token itself was necessary to pay a fee to create new tokens, however other than that there was limited use for it.

Counterparty became the most popular crowdsale platform in the industry. If an entrepreneur or developer wanted to launch a new token, often with a crowdsale, Counterparty was the platform of choice. For nostalgia purposes, below we provide some examples of popular tokens which used Counterparty:

- Storj – The first token for the “decentralised cloud storage” platform, which was later followed by another token on Ethereum.

- LTB – A token awarded to listeners of the popular “Let’s Talk Bitcoin” podcast. After the 2017 ICO bubble, it was eventually possible to swap the tokens for a newer POET coin.

- FoldingCoin – A token rewarding those contributing computer power towards folding DNA, to research diseases.

- GetGems – The native token for an instant messaging and bitcoin wallet app.

- BitCrystals – A token to reward engagement.

- Swarm – The token for a new crowdfunding platform.

There are also examples of tokens which were an early precursor to some of the weakest ideas in the 2017 ICO boom, including FootballCoin and Blockfreight (a shipping logistics token).

In addition to tokens, Counterparty was quick to develop more precursors to technologies which later became popular on Ethereum, including betting, where third party oracles would publish the outcomes of sports games and one could bet on the results, on top of the Bitcoin blockchain. In play betting was even possible. We can remember excitedly betting on the outcome of matches of the 2014 FIFA Football World cup in Brazil, using the Counterparty platform and successfully arbing against traditional custodial sports betting platforms. Counterpary was also quick to implement other features, such as paying dividends to token holders and playing the “Rock, Paper, Scissors” game using the platform.

The most interesting and exciting feature was undoubtedly the Counterparty dex. All the Counterparty tokens could be traded on the dex, which operated on top of the Bitcoin network. A Bitcoin transaction had extra data which could be interpreted by the Counterparty protocol as either a bid with a limit price, an offer with a limit or an order cancellation. If a Bitcoin block contained a matching bid and offer, the protocol would consider the trade executed. At the time one felt incredible excitement using the dex, as if it was the future.

Counterparty’s dex failed to gain traction

Counterparty’s dex failed to gain significant traction, in our view primarily for five reasons:

- User experience – The user experience was not compelling, particularly due to Bitcoin’s target block interval of 10 minutes, which normally means users had to wait several minutes after taking an action like submitting an order, before it appeared on the order book.

- Lack of liquidity – Liquidity on the dex was low and there was little incentive to be a market maker. At the same time adjusting orders was a time consuming and difficult process, which resulted in market makers having to conduct cumbersome and high risk on-chain processes, in order to maintain liquid markets with tight spreads. Market makers were also exposed to the risks of miners front running their orders. Liquidity essentially dried up on the platform for most of the time.

- Scalability – Bitcoin fees were already becoming significant at this point, especially for large Counterparty transactions, which either were multi-signature transactions or later on utilised OP_Return. Having to pay a large fee, perhaps a dollar, just to submit an order, might be too much of a burden for some.

- Perceived Bitcoin culture – Perhaps even more important than scalability was the cultural issue. Some in the Bitcoin community did not welcome this kind of activity on-chain. They considered Bitcoin as more serious than all these “joke tokens”, which many considered would increase validation costs, increase transaction fees or result in misaligned incentives. It is this cultural perception that drove much of the token issuance and dex type activity onto Ethereum, rather than technical factors, in our view.

- Timing – The ecosystem was simply too small and niche at the time to be ready for dexes. Many members of the community were still familiarising themselves with more basic concepts such as transaction confirmations.

Mastercoin eventually rebranded as Omni and the old Mastercoin token was no longer used. USD Tether was then issued on the Omni layer and this eventually became a large success, as Counterparty faded into irrelevance. Given the recent success of dexes on Ethereum and the relatively higher fees on Ethereum, it may be an interesting idea for Omni to implement an on-chain Bitcoin dex and enable USDT/BTC trading.

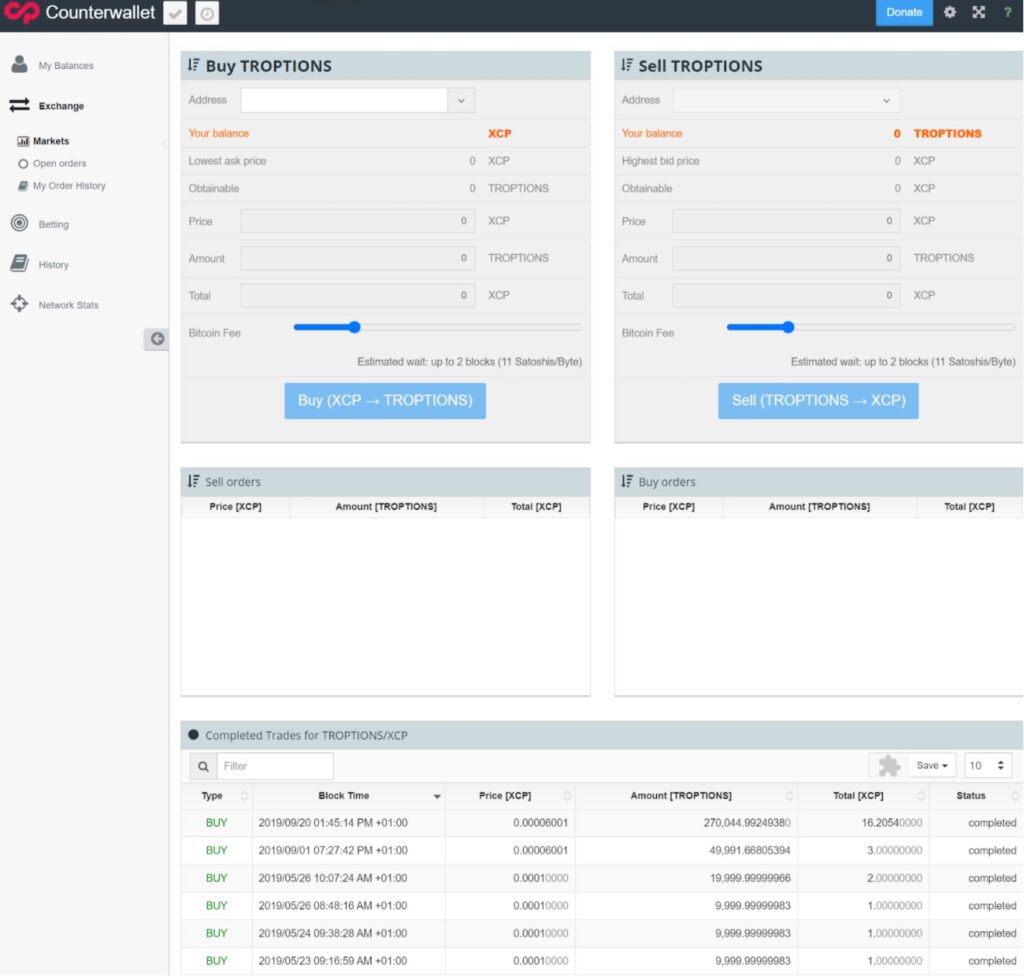

IDEX

The Counterparty model was emulated to some extent on Ethereum by the first generation of Ethereum dexes. Since most of the alternative tokens, by value, now exist on Ethereum rather than Bitcoin, developers have little choice but to select Ethereum as their dex platform. Although this is now changing as many of the popular trading pairs on the “dexes” are tokens like WBTC and USDT, coins with centralised custodians, which could in theory exist on any platform. In our view the most notable and popular of these Ethereum dexes was IDEX. We talked about this a bit in our January 2019 piece.

Like Counterparty, bids, offers and order cancellations were submitted to the Ethereum blockchain, resulting in a centralised order book. However, to solve many of the user experience issues, orders were centrally submitted to an IDEX server first, IDEX then added their signature to the transaction before broadcasting to the Ethereum network. This meant that users had to trust a central entity to determine the sequence of events, but the exchange is still non-custodial. In our view it was essentially a non-custodial exchange rather than a dex, still an interesting achievement and business model. Again exchanges like this failed to generate significant market traction, the primary problem was the difficulty in generating liquidity, due in part to the large amount of on-chain data generated by would be market makers.

Uniswap

The next dex protocol we will look at is Uniswap, which after years of trial and error has finally been a phenomenal success story, with significant trading volume.

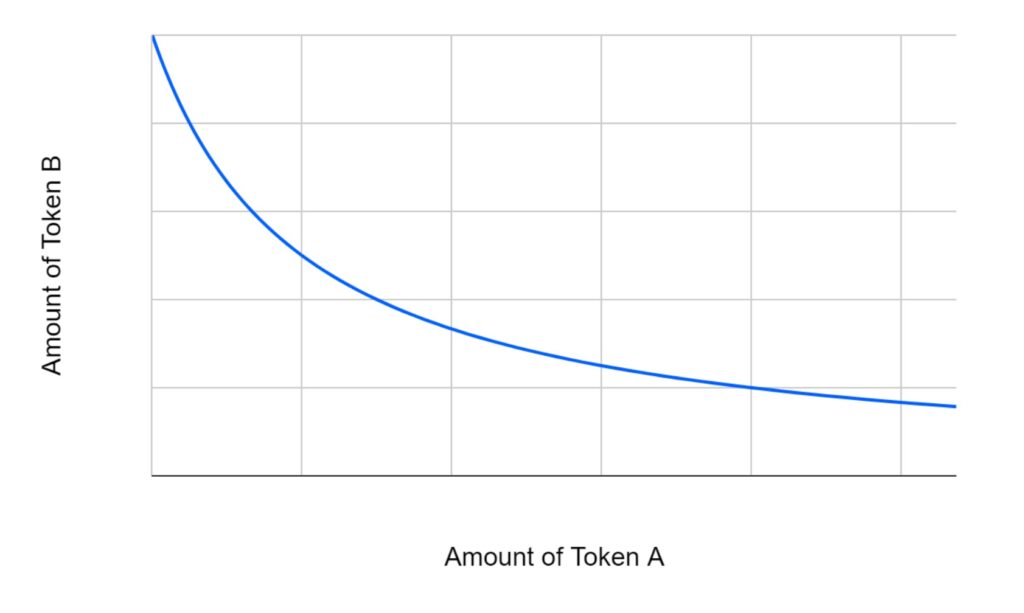

In order to market make in Uniswap, makers lock up tokens into the Ethereum smart contract, there is a separate pool of funds for each trading pair. Makers are incentivised to ensure the liquidity pool is split 50:50 between the two tokens, by coin value. The price of the two tokens can then be calculated by dividing the number of each token locked in the liquidity pool. For example if the pool contains 4,000 USDT and 10 ETH, the ETH price can be calculated as 4,000/10 = $400. In simple terms, this $400 price is the value at which the smart contract allows one to trade ETH for USD or USD for ETH, at least in small amounts.

This ingenious but reasonably simple mechanism incentivises liquidity providers to ensure the value of the two tokens in the liquidity pool is 50:50. If the market price of one of the tokens changes and market makers do not adjust the liquidity pool sizes, traders could exploit this by purchasing tokens at a lower than market price. Going back to our earlier example, if the price of ETH suddenly crashes to $200, traders would be incentivised to use the smart contract to swap ETH for USDT, thereby removing ETH from the contract and adding more USDT to the contract, until the ratio reached 50:50 again.

The above methodology works to some extent, however it needs to address the issue of liquidity, slippage and large orders. The core operating principle behind Uniswap, created to address this liquidity issue, is related to the curve y = 1/x and finding a point on the line which maximises the area under the curve. The x and y-axis represent the number of tokens of each coin in the liquidity pool respectively. Trades will only execute if after the swap, the area under the curve is higher than the area before the swap, including the impact of the 0.3% fee, which is also added to the liquidity pool.

Uniswap price curve illustration

Consider the following two examples, with the same 4,000 USDT and 10 ETH liquidity pool above:

| Example 1: Purchase 1 ETH with USDT | Example 2: Purchase 0.1 ETH with USDT |

| Old area under the curve: $4,000 * 10 ETH = 40,000 | Old area under the curve: $4,000 * 10 ETH = 40,000 |

| Required swap price: $445 New area under the curve: $4,445 * 9 ETH + 1 * 0.3% = 40,005 | Required swap price: $410 New area under the curve: $4,041 * 9.9 ETH + 0.1 * 0.3% = 40,005 |

| New price: 4,400/9 = $488.89 | New price: 4,041/9.9 = $408.18 |

As the above scenarios illustrate, the higher the volume one wishes to trade, the more slippage the trader will experience. The system means there is no orderbook, but merely two pools of funds and this alone is sufficient for trading. This makes market making far easier than constantly using the blockchain to adjust orders. In normal market conditions, without flash price swings, market makers can just provide liquidity into the pool and rely on other liquidity providers to add and remove tokens from the pool, therefore not all market makers need to adjunct their orders, significantly reducing usage of the cumbersome and expensive blockchain. This clever mechanism essentially partly solved the liquidity and scalability problems listed above with respect to Counterparty, at least to some extent the usability issue was partly solved by Ethereum’s faster block target time of only 15 seconds. We therefore consider Uniswap as a strong and innovative protocol, a true dex.

Uniswap copycats

Until September 2020, Uniswap did not have a native token. The 0.3% trading fees all went to the liquidity providers. There is of course an alternative model, where say 0.25% of the fee goes to liquidity providers and 0.05% of the trading fees goes to holders of a native token of the swap protocol. This token could also be issued in part based on usage of the protocol, users could therefore hold the token and be incentivised to use the protocol even more. This token incentivisation model has proved popular in the defi space, where tokens are issued based on some kind of activity and token holders accrue fees. While this model is popular, it also shares many characteristics with ponzi schemes and causes extremely volatile usage patterns on many Ethereum smart contracts. Many of these tokens have aggressive initial issuance schedules, which can cause some to question the sustainability of these business models and protocols.

However, the lack of a native Uniswap token created an opportunity for copycat dexes, to use Uniswap’s methodology, while adding a native token. This native token would then incentivise more use and the new protocol could gain market share from Uniswap. Examples of this include SushiSwap.

Uniswap’s token

A series of these copycat dexes, often for some reason linked to names of food, appear to have caused the Uniswap team to react. In September 2020, they announced and launched a native token for the Uniswap protocol, called UNI. The token issuance will take place over four years, up to a total supply of 1 billion units and around 150 million tokens have already been issued to users of the smart contract. As of now, UNI token holders receive no economic benefits, however they may be able to vote to grant themselves the right to receive trading fees in the future.

The Uniswap team also allocated themselves 21% of the supply. This is something that could be an issue, especially in the context of a dex. The point of a dex appears to be censorship resistance. For example, one can construct an exchange without any fear of a regulatory crackdown or a need to implement KYC systems. With an Ethereum smart contract developers can in theory lock the contract, such that changes are no longer possible and therefore have no control of the exchange, making it a dex. However, if developers have granted themselves an economic benefit by issuing tokens to themselves, regulators could view these individuals just like they view owners of centralised exchanges and potentially crack down on them.

Our position, stubbornly held since Mastercoin in 2013, is that issuing tokens is fine, but allocating tokens to team members or advisors and having an organisation centrally manage the issuance proceeds, represents a significant deterioration in the integrity of the token and exposes the organisation to regulatory risk. However, perhaps this arcane opinion is simply outdated and irrelevant in today’s climate. Even if the team has allocated tokens to themselves, the platform is still very different to a centralised exchange. Firstly, crucially, it is non-custodial and secondly, the component parts of the exchange system have been split up to some extent. For example no centralised IT infrastructure is required. Although, as it happens most people use the Uniswap app on a website presumably owned and controlled by the same team issuing themselves the tokens, rather than manually interacting with the smart contract. It may make Uniswap more resilient if ownership and control of these various components, for example the team tokens and the website app, were more diversified.

The recent defi boom

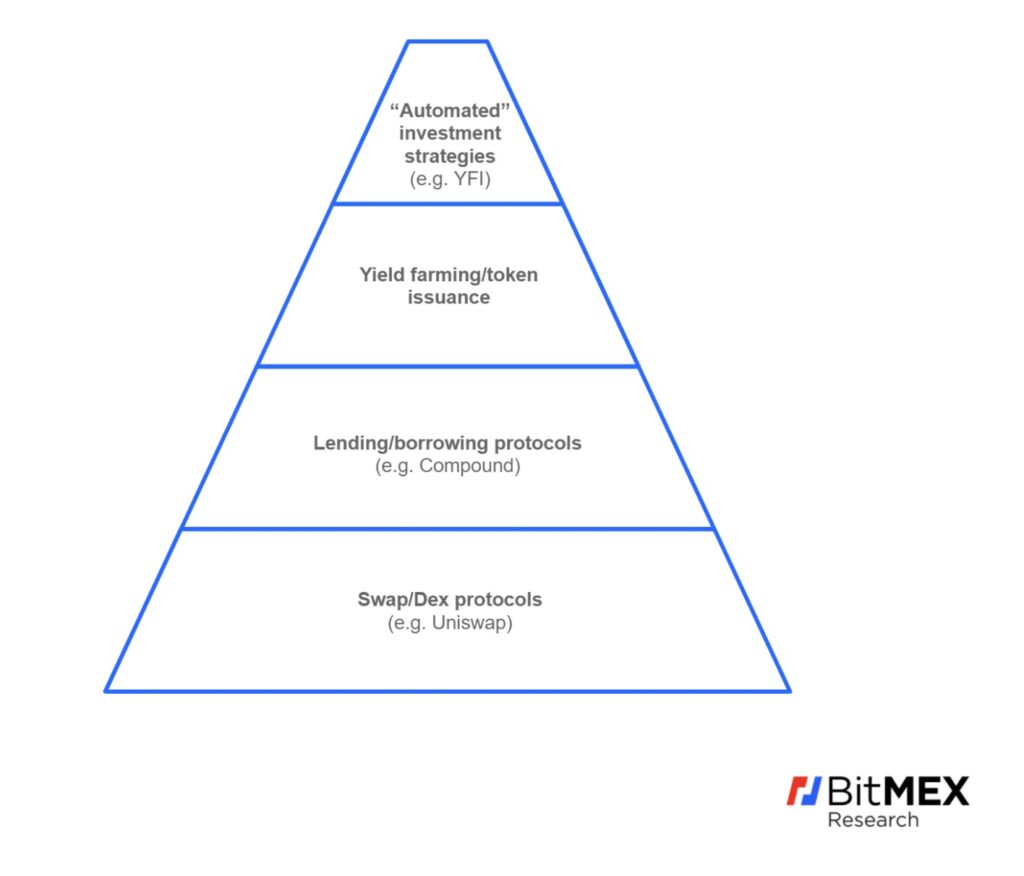

Recently defi has enjoyed phenomenal growth and dexes such as Uniswap have been key to the defi success. Uniswap can almost be considered as a base layer of defi. The recent defi boom has primarily been driven, of course, by a desire to speculate and earn financial returns. We would characterise the drivers of the defi boom into four phases, the last three of which occurred extremely quickly:

- Dexes (2018/2019) – Uniswap launched towards the end of 2018, the protocol enjoyed slow and steady growth until 2020. Uniswap also enabled liquidity providers to earn a decent financial return without taking custody risk.

- Decentralised leverage by combining different protocols (2020) – A key moment for defi growth was the launch of the Compound protocol. This system allows users to lend and borrow assets on Ethereum. In our view, what made this so popular was the ability to combine borrowing with dexes, to increase leverage and speculate on price changes. For example, one can lend ETH on Compound and borrow Dai, then use Uniswap to swap the Dai back into ETH, then lend the ETH out on Compound again. This cycle of re-hypothecation can occur multiple times. Thereby using multiple defi protocols to obtain leverage to increase exposure to ETH. While this does increase risk in the system and can lead to mass liquidations, price crashes and severe on-chain congestion, leverage can be a legitimate part of financial markets and one should not judge this activity too harshly, in our view.

- Yield farming based on new token issuance (2020) – The next wave of adoption, another layer on top of the dexes and lending protocols, was driven by these protocols creating native tokens and issuing them to users of the platforms, offering far higher rates of return due to the token issuances, so called “yield farming”. Again this adoption was primarily driven by speculation and the ability to make financial gains by farming these tokens. This phase depended to a large extent on appreciating token prices and can be considered as unsustainable.

- “Automated” Investment strategies (2020) – The final layer at the top of the defi pyramid, we categorise as “automated” yield maximisation investment strategies. An investment fund type structure is created, which can engage in multiple layers yield farming, lending, swapping and dex liquidity provisioning to earn financial returns. Another set of tokens is then issued to conduct this process. The key example here is YFI.

Defi’s layers of interrelated complexity

Ethereum’s scalability and network fees

This speculative frenzy of activity on the Ethereum network, in the rush to farm the latest tokens, has caused on-chain fees to skyrocket. Network fee prices proved extremely inelastic, as traders desperate to get ahead of their peers proved willing to pay outrageous prices for a confirmation. Ethereum’s total network fees are now higher than Bitcoin and individual Ethereum based protocols like Uniswap are in some periods generating almost as much on-chain transaction fees as Bitcoin. At the same time as the fees spike, the usability of the network is also deteriorating, as users often have to wait a considerable amount of time for confirmations. Transactions also often get stuck and require fee bumping. Some projects are even abandoning Ethereum due to the high fee rates, making their project economically unviable.

In addition to the high fees, Ethereum node operators are also struggling to remain at the tip. Even with our high end 64GB of RAM machine, using Geth we often struggle to ever reach the tip and often remain 5 to 50 blocks behind. Ethereum is very much operating at the limits in terms of validation costs and on-chain fees. Of course Bitcoin avoided this issue, with many in the community recognising years ago that no reasonable blocksize would be big enough and that on-chain data does not effectively scale and retain the censorship resistant characteristic. These individuals are no doubt now thinking:

I told you so…

However, to the Ethereum community, with the huge defi success they have enjoyed, they certainly have no regrets. The difference between the two communities is primarily a cultural one, each having very different time horizons and preferring a different trade-off between robustness and experimentation.

Conclusion

Uniswap is certainly an interesting, ingenious and successful invention. Of course for it to be really interesting there actually needs to be useful tokens native to Ethereum worth trading and investing in. There are custodial tokens representing the USD or bitcoin on Ethereum (Such as USDT, DAI and WBTC), however if the assets are controlled by a centralised custodian, one loses most of the benefits of a dex. On the other hand, breaking an exchange down into these separate components, only one of which is centralised, can improve the resilience of the platform, at least in the medium term. Therefore, even if USDT and WBTC become the dominant tokens on the dexes, defi is still somewhat interesting, in our view.

As for defi, it appears to be a highly complex network of interrelated protocols and a speculative frenzy, primarily driven by new token issuances, which we consider as unsustainable. It shares many characteristics with the 2017 ICO bubble. However, to us at least, and this is not something we felt during the ICO bubble, it appears that hidden deep inside all this complexity, madness and experimentation, there could be something brilliant and sustainable, at least towards the lower layers of the defi pyramid. Uniswap, perhaps before the launch of it’s token, could be the best example of this.