Abstract: In this piece we look over the history of distributed stablecoins, focusing on two case studies, BitShares (BitUSD) and MakerDAO (Dai). We examine the efficacy of various design choices, such as the inclusion of price oracles and pooled collateral. We conclude that while a successful stablecoin is likely to represent the holy grail of financial technology, none of the systems we have examined so far appear robust enough to scale in a meaningful way. The coins we have looked at seem to rely on “why would it trade at any other price?” type logic, to enforce price stability to some extent, although dependence on this reasoning is decreasing as technology improves.

Please click here to download a pdf version of this report

Overview

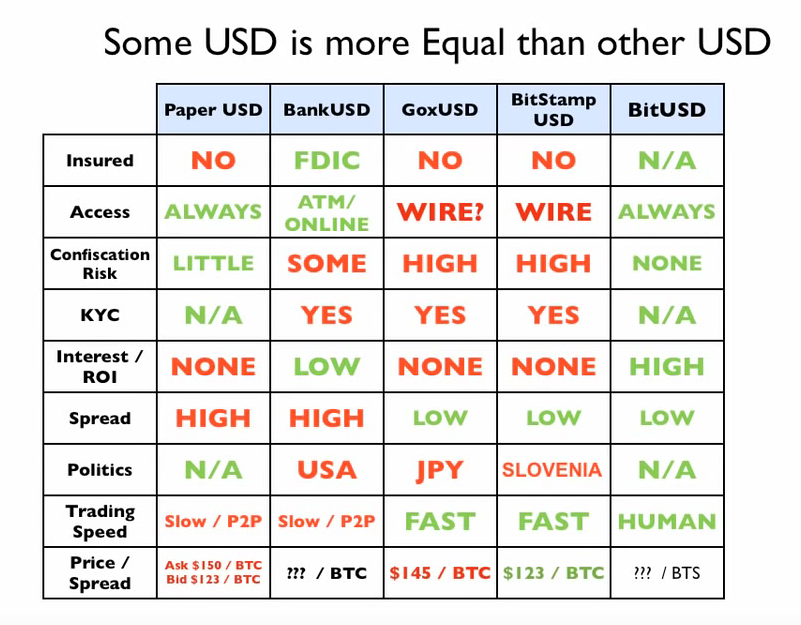

Distributed stablecoins aim to achieve both the characteristics of crypto-coins like Bitcoin (censorship resistant digital transactions) and the price stability of traditional financial assets, such as the US Dollar or gold. These systems are distinct from tokens such as Tether, where one entity controls a pool of US Dollar collateral, ultimately making the system centralised and thus susceptible to being shut down by the authorities.

Along with the somewhat related idea of distributed exchanges, distributed stablecoins have been referred to as the “holy grail” of financial technology, due to their very strong potential benefits. In our view the transformative nature of such a technology on society would be immense, perhaps far more significant than Bitcoin or Ethereum tokens with their floating exchange rates. Distributed stablecoins could have the advantages of Bitcoin (censorship resistance combined with the ability to transact electronically), without the difficulties of a volatile exchange rate and the challenge of encouraging users and merchants to adopt a new unknown token. Such a system is likely to be very successful and therefore it is no surprise that so many people have attempted to launch such projects:

List of stablecoin projects

| Name | Type | Launch Date | White paper link |

| BitShares (BitUSD) | Crypto-collateralized | 21 July 2014 | White paper |

| Nu (NuBits) | Crypto-collateralized | 24 Sept 2014 | White paper |

| Steem (SteemUSD) | Crypto-collateralized | 19 April 2016 | White paper |

| Corion | Non-collateralized | 14 Oct 2017 | White paper |

| MakerDAO (Dai) | Crypto-collateralized | 27 Dec 2017 | White paper |

| Alchemint | Crypto-collateralized | Sept 2018 | White paper |

| BitBay | Non-collateralized | Sept 2018 | White paper |

| Carbon | Non-collateralized | n/a | White paper |

| Basis | Non-collateralized | n/a | White paper |

| Havven | Crypto-collateralized | n/a | White paper |

| Seignoriage Shares | Non-collateralized | n/a | White paper |

The technical challenges involved in creating such systems are often underestimated. Indeed constructing a distributed stablecoin system, which is robust enough to withstand cycles or the turbulence and volatility linked to financial markets may be almost impossible. For instance perhaps most forms of fiat money, even the US Dollar itself, have not even achieved that, with credit cycles putting US Dollar bank deposits at risk. A stablecoin system which builds on top of the US Dollar is therefore never going to be more reliable than traditional banking, in our view.

In economics there is a concept of money supply, with risk and the potential inflationary impact increasing as the number of layers increase. One could add this stablecoin systems on top, as a new high risk layer:

- M0 – Notes & coins plus deposits at the central banks

- M1 – Money on deposit in a bank current account (including M0)

- M2 – Money on deposit in a bank savings account (including M1)

- M3 – Money in a money market account (including M2)

- MZM – Money in all financial assets redeemable on demand (including M3)

- MSC (Synthetic Crypto Money) – Money inside synthetic crypto stablecoin systems (including MZM)

However advanced or sophisticated the distributed stablecoin technology is, we believe the token is likely to be less robust than the layers above it in the money supply tree.

In this piece we review some of the most prominent and interesting attempts at building these synthetic US Dollar type systems. BitUSD in 2014 and then a more recent project, MakerDAO (Dai).

Case study 1: BitShares (BitUSD) – 2014

| Factbox | |

| Coin Name | BitUSD |

| Launch Date | 21 July 2014 |

| Crypto collateral | Yes |

| Price oracle | No |

The first stable coin we will discuss is BitUSD, a stablecoin on the BitShares platform. BitShares was a delegated proof of stake (DPOS) platform launched in 2014 by:

- Daniel Larimer (The primary architect behind EOS and Steem),

- Charles Hoskinson (the former Ethereum Foundation CEO & Cardano architect), and

- Stan Larimer (Daniel’s father).

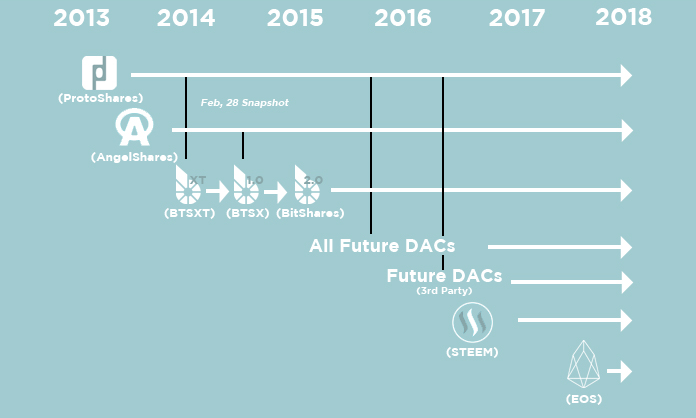

BitShares is just one in a long line of decentralised autonomous corporation (DAC) type platforms released by Daniel Larimer, as the below image shows:

(Note: Daniel Larmier’s company Invictus Innovations launched a number of token/DAC platforms including Protoshares, Angelshares and BitShares. The black arrows represent Protoshares coin holders being granted tokens in the new chains, which Invictus Innovations promised to deliver on all new DAC platforms. Source: BitSharestalk)

BitUSD Marketing material

(Source: Introduction to BitShares Youtube video)

BitUSD System dynamics

| Pools of Funds | Description |

| Bitshares | The native currency of the BitShares platform |

| Bitshares held as collateral | Separate pools of Bitshares held as collateral, used as backing for the stablecoin. |

| BitUSD | The stable token, designed to track the value of the US Dollar |

| Groups of Participants | Description |

| BitUSD holders | Investors and users of the BitUSD stable coin. Holders of BitUSD are able to redeem the tokens for the Bitshares held in collateral. |

| BitUSD creators | Those that create new BitUSD, by selling it into the market (creating new loans), by posting BitShares as collateral. This loan may be for a small period of time, after which it needs to be rolled over or have its collateral topped up to the initial margin level. |

| Traders | Those exchanging BitUSD for Bitshares, and vica versa, on the platform’s own distributed exchange. There is therefore a Bitshares vs BitUSD market price. |

| Block producers | Bitshares block producers/miners have a role of spending the BitShares backing BitUSD, something they are only entitled to do if the value of the BitShares is less than 150% of the value of the BitUSD it is backing (based on the BitUSD vs BitShares exchange rate on the system’s own distributed exchange). The miner can then uses the Bitshares to redeem/destroy the BitUSD. (After the launch the 150% margin level was increased to 200%) |

| Price Stability Mechanisms | Price Direction | Description |

| Investor psychology (Unclear/”Why not trade at $1?”) | Both directions | There does not appear to be a specific price stability mechanism in the BitUSD system. One can redeem and create BitUSD, however the price this transfer occurs at is determined by the BitUSD vs BitShares price in distributed exchange, which is not linked to “real USD”. In a way the price references itself. There is therefore no direct mechanism keeping the price of BitUSD at $1, but the argument put forward is “why would it trade at any other price?” In our view this logic is weak. |

| BitUSD redemption (indirect) | Positive | Should the value of the collateral currency (BitShares) fall, any BitUSD holder can redeem the BitUSD and obtain $1 worth of BitShares, assuming the market price of BitUSD is still worth $1 and there is sufficient BitShares held in collateral.

This stability mechanism protects the integrity of the system only in the event that the value of BitShares falls and the BitUSD market price remains at $1. It does not directly stabilize the price of BitUSD around $1, in our view. If the price of BitUSD deviates from $1, this mechanism may not help correct the price. In our view, it is important to draw the distinction between a mechanism designed to protect the value of collateral and that of a mechanism which directly causes the price of the stablecoin to converge. |

Weaknesses

Exposure to a fall in the value of collateral – BitShares was a new, untested and low value asset, and therefore its value was volatile. If the value of the token falls by 50% sharply, in a period spanned by one of the loans used to create BitUSD, there may be insufficient collateral and the peg could fail.

Lack of a price oracle – In our view one of the most controversial aspects of this design is the absence of any price oracle mechanism, providing the system with real world exchange rates. However any price oracle system is challenging to implement and may introduce several weaknesses and avenues for manipulation. We will talk more about this in part 2. In our view, the only real way around this may be that any stablecoin system may require a price feed from a distributed exchange, which can in theory publish a distributed price feed from real world US Dollar transactions. The distributed exchange in BitShares did not allow “real USD”. A distributed exchange system like Bisq, without a central clearing could in theory allow “real USD” prices and provide a distributed price feed. Therefore stablecoins may eventually be considered as a layer two technology on top of liquid and robust distributed exchange platforms, should these systems ever emerge.

Manipulation – Trading volume in the Bitshares vs BitUSD market on the distributed exchange platform was low, it was therefore possible for block producers to manipulate the market by causing the value of Bitshares to fall relative to BitUSD, enabling them to obtain Bitshares at a discount.

Lack of any price stability mechanism – The main weakness of the system is the lack of any mechanism to move the price towards $1, other than the “where else would it trade?” logic.

Daniel Larimer’s defence of the system

In Daniel’s view, the mechanism of BitUSD creation is analogous to how USD are created in the economy, in that financial institutions lend them into existence.

It’s the same way dollars are created in the regular banking system. Dollars are learnt into existence backed by collateral, in the case of the current banking system the collateral is your house. In the case of our system its shares in the DAC itself.

(Source: Lets talk Bitcoin episode 129)

In a way Daniel is correct here, however as we explained in the introduction to this piece, these synthetic dollars are far less reliable than those created by more traditional banks, and can be considered as a whole new layer of risk, as they are even further away from base money. In addition to this, when obtaining a bank loan, the bank typically has a legal obligation to provide the customer physical cash should they demand it. While such an outcome for BitUSD holder is possible, its not a legal obligation for the creators of BitUSD. Although obviously banks typically do not have the cash in reserve to pay back their deposits, we think the fact they have a legal obligation to do so is an important distinction to draw when comparing BitUSD to US Dollar banking deposits.

In response to the supposed weakness of a lack of a price peg, Larimer argues in favor of his “hypothesis that the price feed is unnecessary” as follows:

It implements automatic margin calls, such that if the price moves against someone who is effectively short, it forces them to cover and buy it back in the market and that creates a peg. The market peg works on the premise that all market participants buy and sell based on what they think market participants will be buying and selling in the future. The only rational choice is to assume that it’s going to trade based on the peg in the future. If you don’t believe that they you have to decide on which way it’s going to go, up or down. And if you don’t have a way of saying you abstain from the market. If you don’t think it works you sell the shares and get out, as the systems going to fail in the first place. So its a self reinforcing market peg, that causes the asset to always have the purchasing power of the dollar.

(Source: Lets talk Bitcoin episode 129)

In our view this idea that a price of $1 is the “only rational choice” is a weak argument. It is basically saying that if the price is not $1, then what will it be? This logic may hold true for some periods, but it is not sustainable and will not scale, in our view.

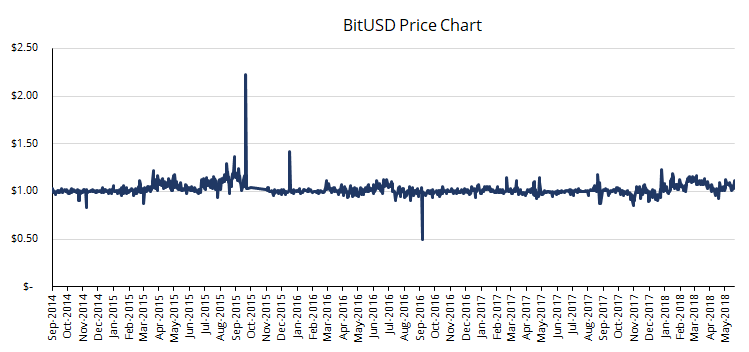

Conclusion

The volume of BitUSD in existence was a lot lower than many had hoped, in some periods there was only around $40,000 in issuance. At the same time liquidity was very low and the price stability was weak, as the below chart illustrates. The main architect of BitUSD went on to propose a new stablecoin SteemUSD in 2017, this time including a price feed system. Therefore we consider BitUSD as an interesting early experiment, it did not achieve what was hoped nor did it build a robust stablecoin.

(Source: Coinmarketcap)

Case Study 2: MakerDAO (Dai) – 2017

| Factbox | |

| Coin Name | Dai |

| Launch Date | 27 Dec 2017 |

| Crypto Collateralized | Yes |

| Price Oracles | Yes (indirect) |

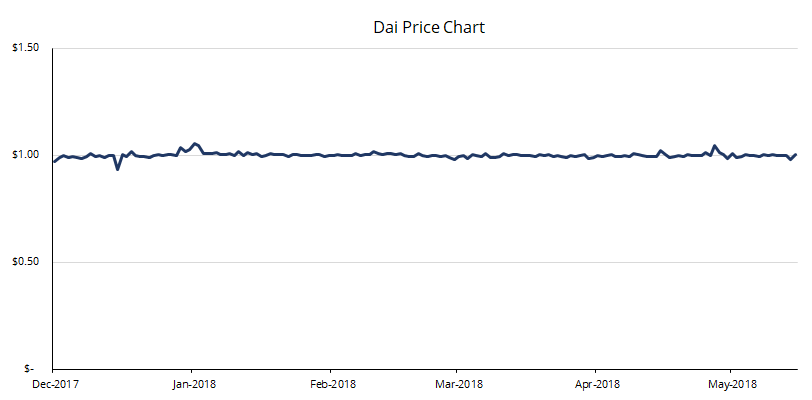

The next stablecoin we look at is Dai, which exists on the Ethereum platform. This system is highly complex, with four relevant pools of funds and six possible stability mechanisms. There are currently around $50 million worth of Dai in issuance and the peg seems to be holding up reasonably well.

System dynamics

| Pools of Funds | Description |

| Ethereum | Ethereum is the native token of the Blockchain platform used for Maker & Dai |

| Pooled Ethereum | Ethereum is placed in pools used as collateral for issuance of the Dai token. These are often referred to a collateralized debt positions (CDPs) |

| Dai | Dai is an ERC-20 token that is generated by collateralizing pooled Ether. Dai is the stablecoin token, designed to be valued at $1. |

| Maker | The Maker token is MakerDAO’s governance token. It is used to vote on various initiatives that pertain to the stability of the ecosystem. It is also mandatory to possess during the collateral unlocking process. During such a process, a stability fee is garnered from the user, where payment is accepted exclusively in Maker. Maker is also an ERC-20 token. |

| Groups of Participants | Description |

| Dai Creators | An individual who sends Ethereum to a smart contract, locking up Ethereum in exchange for Dai. These people are also known as CDP owners. |

| Dai Holder/User | A Dai holder may or may not be a Dai creator. They may invest in or use the Dai stablecoin token. |

| Maker Token Holders | Maker token holders vote on several functions and parameters of the MakerDAO system. They manage aspects such as stability fees and liquidation ratios, as well as having responsibility to nominate other groups. |

| Keepers | These traders monitor the Dai collateral and if it falls to an insufficient level, purchase the collateral in an open auction, by spending Dai. |

| Oracles | Price feed producers submit price information that is aggregated and used to select a given price for both Maker and Ethereum (but not Dai itself). These agents are nominated by MakerDAO token holders.

In order to prevent manipulation, there is a one hour lag between the price publication and when it impacts the system. In addition to this a median type mechanism is used to select the price, which involves ignoring the highest and lowest prices. In our view this may not prove to be robust enough if the oracles have a conflict of interest and try to engage in manipulation. |

| Global settlers | This is another group nominated by the MakerDAO token holders. This group can unwind the entire Dai system, by giving Dai holders the right to redeem their collateral at a fixed price. |

| Price Adjustment Mechanics | Price Direction | Description |

| Dai Redemption | Positive | The primary stability mechanism is the ability, in theory, to redeem Dai for $1 worth of Ethereum. Redemption can only be conducted by CDP owners (unless there is insufficient collateral). If the price of Dai falls, CDP owners need to either use Dai they currently hold or buy it in the market, and then they can redeem/delete Dai for $1 worth of Ethereum based on the price feed provided by the price oracles. |

| Dai Creation | Negative | To complement the Dai redemption process, the mechanism to prevent the price of Dai climbing too high, is the ability of Ethereum holders to create new Dai, by placing Ethereum inside of CDPs. |

| Target rate (Not active) | Both directions | There is a “Target Rate Feedback Mechanism” (TRFM), which appears to be another price stability mechanism in the system. However, it is not yet active nor have several specifications of the mechanism been worked out yet.

The the idea is that a target rate is set by the MakerDAO token holders. The target rate is essentially a spread which applies to the creation or redemption of Dai, designed to correct the price. |

| CDP liquidation (indirect) | Positive | There is a mechanism by which traders/keepers can redeem the Ethereum collateral held by another CDP. This can only occur if the value of this collateral falls to an insufficient level to backup the Dai, in this case 150% of the value of Dai. This should incentivise CDP owners to keep topping up their CDPs to ensure there is a large buffer of Ethereum.

This is a necessary mechanism to ensure the integrity of the system and ensure the value of the collateral is always sufficient. However it is not clear if this directly keeps the value of Dai at $1. This mechanism can be thought of as a building block on the stability mechanism, which merely ensures the level of collateral is sufficient. Other redemption systems are needed to make this meaningful, in our view. |

| Global Settlement | Positive | This mechanism can be triggered at any time. The triggering essentially gives all Dai holders an option to convert back to a fixed value of Ethereum, worth $1 according to the oracle price feed, at the time of the triggering (or whatever price is possible given the total level of collateral in the system). The difference between this and normal redemption, is that the price is fixed and its open to all Dai token holders and not paired to a particular CDP.

The idea is that this mechanism can be used as a threat against CDP holders, to ensure they keep redeeming Dai in the event the price falls, rather than holding out for an even lower price. Global settlement can also be used in the event of bugs or other emergencies. |

| MakerDAO token issuance (indirect) | Positive | MakerDAO token holders act as the buyer of last resort. If the collateral (pooled Ethereum) in the system were to drop below 100% collateralization, MakerDAO is automatically created and auctioned on the open market to raise additional funds to collateralize the system. Hence, if the system becomes undercollateralized, Maker holders absorb the damage.

Again this mechanism protects the value of collateral, but does not directly help the price of Dai converge to $1, in our view. |

Analysis of the core stability mechanism – Dai redemption

The primary stability mechanisms appear to be the ability of CDP owners to redeem if the price of Dai is too low and for people to create new Dai if the price is too high. For example if the price of Dai falls to 80 cent, CDP owners could purchase Dai in the market and redeem it, unlocking $1 worth of Ethereum and making a nice profit. This is how the system should work under normal circumstances.

The above appears to be a robust stability mechanism which should keep the price of Dai at or near $1. However, the theory may only work if CDP owners expect the price of Dai to correct back to $1. If the price of Dai has fallen to 80 cent, CDP owners may be reluctant to redeem if they expect the Dai price to fall further to 60 cent, as such a price would enable them to make even more profit. There is no guarantee that once the price reaches 80 cent, it won’t continue to fall.

Therefore the stability mechanism could depend somewhat on the power dynamics between two groups, Dai owners and CDP owners. These two groups are essentially trading against each other in the market, Dai owners are selling of Dai and CDP owners are the potential buyers. If the power balance shifts towards CDP owners, such that they are well capitalised, patient, collaborative and determined, this group could outmaneuver the Dai token holders, drive the price down, and then buy it back and make a large profit. This may seem unlikely, but in our view the stability mechanism may not work in all market scenarios. Although we consider Dai as superior to BitUSD, in some limited ways, the Dai peg relies on market psychology and investor expectations, in the same way as BitUSD. Therefore the Dai peg is also weak and unlikely to scale.

The global settlement system can mitigate the above risk. If CDP owners are successfully manipulating the price of Dai down too far, this could trigger global settlement. Dai holders would then get around $1 of Ethereum back. Therefore the threat of global settlement may keep the price of Dai up. However again the effectiveness of this threat depends on the determination of the various groups, the CDP owners, MakerDAO token holders and global settlement activators.

Conclusion

We consider Dai to be one of the most sophisticated and advanced stablecoins systems which has been produced so far. In our view, when digging into Dai’s stability mechanisms, there is no one powerful mechanism which ensures stability. Instead we have a complex network of systems, which to some extent reference each other and use circular logic. One could claim this complexity was created to obfuscate the lack of a strong and clear stability mechanism, but it is more likely to be an indication of an experimental trial and error type approach to the design of the system.

Therefore the system is still reliant on investor expectations and psychology, although to a lesser extent than the BitUSD. While the stability systems in place could work, at least for a while, we think they are not robust enough to withstand market turmoil or some types of power imbalances between Dai holders and CDP owners. Therefore, the search for the holy grail continues.