Abstract: We examine the issue of the carbon footprint associated with Bitcoin mining. We argue that the most effective way for users and exchanges to evaluate the situation is through the lens of onchain transaction fees, which is the primary way users directly incentivise miners to conduct their energy intensive behavior. We provide our own very basic and conservative calculation which attempts to estimate the carbon footprint of spending US$1 on transaction fees, whilst to a limited extent considering Bitcoin’s unique energy characteristics, which incentivises low cost energy usage and potentially the use of otherwise trapped power. Like any methodology for measuring the carbon footprint of Bitcoin, ours is flawed, contradictory and controversial, however we believe there is no reasonable approach to this issue which will fully satisfy the critics and our approach improves upon some of the others out there.

Overview

Following on from the Elon Musk Tweet on 12 May 2021, which complained about the high level of carbon emissions related to Bitcoin mining, as a thought experiment we decided to look into the situation and perhaps calculate the carbon footprint related to BitMEX’s Bitcoin transactions.

The first thing to note is that this is a complex and controversial topic – calculating carbon emissions for almost any economic activity can be extremely difficult and this is especially true for an incentive-based system like Bitcoin. Any policy or calculation will be fraught with contradictions and errors. It therefore is almost impossible to come up with a response to this question which will satisfy the majority of people and any analysis will have several critical flaws. Nethertheless, we looked at the issues. Inspired by several other very poor attempts, which often involved amortising the block subsidy over the onchain transactions to get a ludicrously high per transaction carbon cost, often two orders of magnitude higher than any realistic guess, we were convinced we could at least produce something better than that. One could argue that if you want to allocate the carbon costs of mining Bitcoin, investors/holders, investment product providers and custodians could be allocated the environmental costs incentivised by the block reward. While, on the other hand, users, merchants and exchanges could be allocated the environmental costs incentivised by the transaction fees and transactions.

In this piece we attempt to form a new methodology for estimating the carbon footprint of Bitcoin transactions, with a system which partly reflects some of the positive aspects around Bitcoin’s energy footprint. It is only meant as a rough estimate and something to be used in the short term, not a long-term solution.

Before reading any further, we would recommend looking at our September 2017 piece on Bitcoin’s energy consumption, explaining why China and hydropower were so dominant as Bitcoin power sources back then. This was the first major piece from BitMEX Research and although the report is a bit dated now and the narrative has moved on, as far as we can tell it is the first detailed look at why Bitcoin mining is a genuinely unique type of electricity demand, because it doesn’t need to be located near the end users of the energy.

In general, people have such different opinions on Bitcoin that it is difficult to talk about Bitcoin’s energy consumption, as these different opinions will lead to very different conclusions. Below we have split people into three groups with different opinions on Bitcoin and how they may consider the energy used in Bitcoin mining.

Group 1 – Bitcoin is totally useless and therefore in an unsustainable price bubble

In this group, one likely thinks that Bitcoin is a totally useless invention. The rapid price appreciation of the coin has been driven by misconceptions about the technology and a sensational bubble which can be characterized by the Charles Mackay book “Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds”. On top of this, the situation is considered exceptionally bad, because unlike many other manias, this particular mania has a negative externality of causing a large amount of environmental damage. Most of the critics of Bitcoin mining’s energy use appear to fall into this group. People here are unlikely to be convinced by the argument that Bitcoin mining is one of the only “geography neutral” forms of energy demand and therefore extremely environmentally friendly. If Bitcoin is ultimately useless, so what?

However, people in this group concerned about the environment can at least draw some comfort. If this is true, the ‘unsustainable’ price bubble will eventually burst and the incentive for Bitcoin mining will diminish. This is therefore not a long term environmental problem. Environmentalists in this camp could try educating investors about Bitcoin’s ‘uselessness’ or overvaluation to try to reduce the level of environmental damage the system causes in the short to medium term.

In the recent wave of Bitcoin price appreciation, many of Bitcoin’s critics have become quite pessimistic. After witnessing several monumental cycles of Bitcoin price appreciation over many years and still firmly believing Bitcoin to be a fundamentally useless system, some people have formed a somewhat negative view about the investing public and their continued appetite to invest in Bitcoin despite its ‘uselessness’. Therefore they see no end in sight to Bitcoin’s rapid rise and expect continued pointless environmental damage years into the future. It seems old phrases like “Bitcoin is here to stay” are now becoming widely accepted, even by the coin’s critics. If you fall into this group, but believe Bitcoin is going to stay around, then perhaps yes, Bitcoin is very bad for the environment and there is not much more that can be said. Although, there are all kinds of behavior people conduct that others may view as pointless, which can be damaging to the environment. One could argue environmentalists shouldn’t let their personal tastes and dislikes about the activities of others impact their environmentalist campaigns. However, this demand is probably unrealistic.

Group 2 – Bitcoin may have some useful characteristics which can be achieved in a system without proof of work

There is then a second group who believe that there is something interesting about Bitcoin, but that proof of work is not an integral part of this. For instance, perhaps crypto in general is interesting, namely the idea of transactions using public private key cryptography where the receiver verifies the signature of the sender. In our view this is mostly muddled thinking and using digital signatures becomes far more interesting in a decentralised system, where the private key represents the ultimate form of ownership.

On the other hand, one could believe a censorship resistant consensus system is possible with a less energy-intensive mechanism such as proof of stake. We concede that if proof of stake systems can be shown to effectively work and scale, then yes, Bitcoin could be at a disadvantage given its relative energy use. We plan to take a look again into proof of stake systems in the coming months, following on from our original look at the topic in April 2018.

Group 3 – Bitcoin may have useful characteristics and is inextricably linked to proof of work

Then there is a third group that most people in our audience probably would sympathise with The concept of a competition to use as much electrical energy as possible to decide on potentially conflicting transactions, is precisely the point of Bitcoin. Removing this from Bitcoin is impossible because this is almost the defining characteristic. Bitcoin also has inherently useful social utility, not least as a tool to enable those blocked from the financial system to engage in financial transactions without restrictions from those trying to oppress them. Bitcoin is therefore considered as having an extremely positive impact on society, well worth its environmental impact.

Those in this group might think efforts to address environmental concerns are therefore mostly pointless or “virtue signalling”, as why should this use of energy be singled out for criticism compared to all the others? What about other wasteful activities such as war or private jets?

Amortising the block subsidy over total transaction volume

Some entities attempting to estimate the electricity consumption per Bitcoin transaction often have extremely large values. For instance, the statista.com webpage estimates that each Bitcoin transaction requires over 1,662 kWh of electricity, compared to 100,000 VISA transactions which requires only 148 kWh of electricity – a difference of around one million times. This claim seems somewhat preposterous, since 1,662 kWh of electricity is likely to cost several hundred US dollars. A Bitcoin transaction currently has a median fee of around US$4. Why would miners spend hundreds of dollars in electricity bills only to earn a few dollars? It defies basic logic and this high figure of over 1,000 kWh per transaction provides very little meaningful information about Bitcoin, mining, or energy consumption. Clearly, if a Bitcoin user includes a US$4 fee on their transaction, they are incentivising or causing a maximum of around US$4 of electricity usage, which is around 30 kWh per Bitcoin transaction, not 1,662 kWh.

What these very high energy use estimates are doing is amortising the block subsidy, currently 6.25 bitcoin, across all of the onchain transactions. Using the block subsidy can be useful when estimating the total energy consumption of the Bitcoin system, but it seems odd to use this for a per transaction calculation. After all, there is nothing individual users can do about that, as they are only responsible for the fees they pay and it is those fees that incentivise any additional mining related to the transactions. In addition to this, the block subsidy can be thought of as ensuring the viability of the entire system, if one is going to amortise this cost over all the transactions, one could consider including off-chain transactions such as Lightning or on custodial systems such as Coinbase, BitMEX, or the ProShares Bitcoin Strategy ETF (BITO US).

It’s also important to note that the block subsidy is set to exponentially decline until eventually it approaches zero. Therefore this is not a long-term environmental problem and as Satoshi put it: “incentives will transition entirely to fees”. Therefore, in our view, the most effective way for exchanges to look at the issue is through the lens of transaction fees. i.e. How much electricity usage is incentivised per US dollar spent on transaction fees.

Regardless of your view of this approach (even if you fall into group 3), at least there is the potential for a positive outcome. If people become more concerned about minimising average transaction fees (for whatever reason) it could encourage adoption of block weight saving technologies such as batching, SegWit, and Lightning. At the same time as improving environmental efficiency, these technologies also potentially make Bitcoin more useful and user friendly and are therefore a win-win solution.

Exchange carbon offsetting

Cryptocurrency exchanges, such as BitMEX and FTX, have committed to offset the carbon emissions caused by crypto miner energy use, associated with their Bitcoin transactions. The first question this raises is why? Why offset the carbon related to Bitcoin transactions, rather than any other aspect of the businesses, for instance the web server bills. Exchanges probably pay much more for web servers than Bitcoin transaction fees, therefore one may assume this does more environmental damage. And even if you are going to offset the impact of transaction fees, why only target miner electricity use, rather than other aspects of mining such as production of the machinery or the costs to transport the machinery to the site?

However, despite these questions (which probably warrant a whole book’s worth of material) exchanges have decided to enact this policy and therefore it deserves our scrutiny and analysis.

Environmental impact of crypto mining

The truth is cryptocurrency mining is a pretty energy-intensive activity. For every dollar spent on transaction fees, perhaps around 70% of this is likely to incentivise the usage of electrical energy. This is pretty high compared to some other products or services. This intensity may have partly contributed to the concerns about Bitcoin’s environmental impact. However, despite being extremely energy intensive, per unit power consumed, Bitcoin mining is probably one of the most environmentally friendly activities in the world. This is due to the unique flexibility with respect to where the power is required. This means miners often choose renewable power due to the low stable costs or miners are able to use otherwise wasted or stranded energy. This is a fact often claimed by Bitcoin proponents and it is probably true. Per unit power consumed Bitcoin is likely to be exceptionally environmentally friendly.

However, what about per US dollar spent on power? How does Bitcoin mining stack up using this metric? Here the situation is a bit less clear. Bitcoin is probably still quite a lot better than the global average, due to the high renewable energy mix. Even when Bitcoin miners use fossil fuels, due to the low energy price they require, the Bitcoin miners are never likely to act as a catalyst for new energy projects, which is a positive with respect to the environment. Therefore, Bitcoin mining should still be considered as pretty environmentally friendly. However, remember the incentive is for miners to consume as much power as possible, not directly to use green energy.

Critics could even make the case that these two factors, geography neutral demand and the incentive to use as much energy as possible, offset each other. Thereby negating the incentive to use low cost clean or otherwise wasted power assets. Therefore, these critics could claim that per US dollar spent on Bitcoin electricity, Bitcoin could generate just as much carbon as the global average. Although of course there is no particular reason to believe these two things do offset each other and this is not an approach we agree with, however for the sake of simplicity, it is this very conservative approach that we have chosen to consider further. This is not perfect, but better than some of the calculations others have used, where they assume a bad scenario for each factor, high power consumption with no mitigation for the cleaner energy.

Calculating the carbon cost of transaction fees

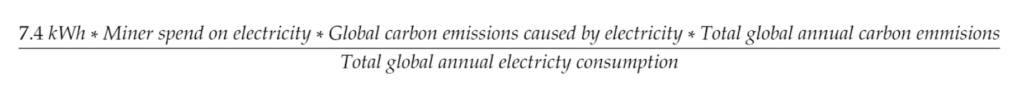

As discussed above we have already decided to focus on transaction fees. What we want is some kind of estimate of the tonnes of carbon emitted for every one US dollar spent on fees. This is somewhat equivalent to the quick calculation performed by FTX CEO Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) in his May 2021 Twitter post. Given the uncertainties involved, the back of the envelope type estimate is probably most appropriate. We also want something to reflect the unique energy characteristics of Bitcoin, the geography-neutral energy demand, and incentive to use low cost power, power from otherwise failed energy projects, or waste energy. Of course this is complex and cannot easily be represented or estimated in a quick formula.

The imperfect method we came up with was to compare the average electricity cost in kWh for Bitcoin mining to the global average cost per kWh of electricity. This very rough proxy can provide an imperfect and somewhat conservative economic estimate of the environmental savings of one kWh used to mine Bitcoin compared to one kWh used to do anything else.

While this method is obviously very flawed, like almost any other system, the good thing about it is simplicity. Rather than delving into the nuances of hydropower or trapped natural gas, one simply uses average prices. On the other somewhat positive aspect of it is you can remove or “cancel out” the estimate of Bitcoin mining electricity costs from the equation, as we explain below.

For example if one spends US$1 in transaction fees and the average cost of electricity used in Bitcoin mining is US$0.06 per kWh, one can argue that this US$1 of spend has incentivised the consumption of at most 1/0.06 = 16.7 kWh of electricity. Assuming the global average electricity costs is around double this, US$0.135 per kWh, the fact that Bitcoin mining is around half this cost is a positive characteristic reflecting efficiency. The lower cost indicates Bitcoin may be more environmentally friendly and efficient. Other estimates we have seen use this lower cost to estimate higher electricity usage and then assume the same environmental damage as average global electricity usage; our methodology is at least fairer than this, which avoids double counting a negative.

Therefore we propose amending the formula proposed by SBF, instead of using the estimated electricity costs of Bitcoin miners to estimate electricity usage, we use the global average electricity costs. Of course to be consistent, we also have to remove any assumption about renewable energy (⅓ in Sam’s case), as this could be double counting to some extent. Therefore, using this new – albeit sure to be controversial – methodology, we now assume each US$1 spent on transaction fees could incentivise up to 1/0.135 = 7.4 kWh of typical electricity usage.

The theory used to justify this logic is that if Bitcoin miners find cheaper cleaner energy, that will only encourage more energy spend and vice versa, therefore Bitcoin energy costs are excluded from the calculation and we use the global average. We still think this is a somewhat conservative assumption, for instance Bitcoin could incentivise the use of so much clean or otherwise wasted energy that a price higher than the global average could be used to estimate the equivalent electricity usage. What our methodology essentially does is calculate the carbon emissions which would occur if the Bitcoin transaction fees went to generic or average global electricity consumption. In reality Bitcoin is likely to be more environmentally friendly than average (per US dollar spent) and therefore this is a conservative assumption, however, we think this is clearly better than some of the other estimates out there.

Once we have this 7.4 kWh figure, we can then multiply across to estimate the carbon footprint of US$1 spent on Bitcoin transaction fees.

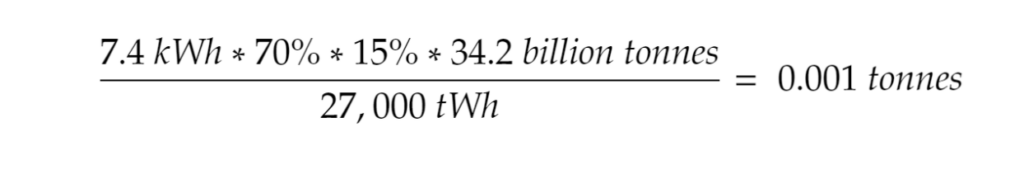

Plugging the numbers into the formula, the number we get is that $US1 spent on Bitcoin transaction fees can incentivise up to 0.001 tonnes of Carbon emissions.

The global energy related figures come from BP’s Statistical review of world energy (2020).

Carbon offsetting price

Once one has a model for how many tonnes of carbon they want to offset, you can consider “offsetting” the carbon, which means paying a third party to conduct some kind of activity to offset the damage, such as planting trees. Yet we must also acknowledge that this is also an imperfect solution for the following reasons:

- These schemes could not scale to offset all global emissions. They represent the lowest cost method of offsetting one tonne of carbon, but offsetting all global carbon emissions would be far more expensive. These schemes typically cost between $5 and $35 to offset one tonne of carbon. If an organisation wanted to offset their carbon emissions based on the global average cost of offsetting all emitted carbon, the cost is likely to be at least an order of magnitude more expensive.

- The methodologies used to calculate offsetting carbon emissions can be tricky – just like our exercise to estimate the carbon emissions. For example if a tree is planted there is no guarantee with regards to how long the tree will remain in the ground. Some offsetting calculations, therefore, could be too optimistic or otherwise flawed.

- There is also the argument about economic inequality and that offsetting allows for the wealthy to carry on with their carbon emitting lifestyle with a clear conscience, while the poor are now less able to afford certain luxuries, due to high offsetting charges.

In addition to carbon offsetting, the EU for example has a carbon trading scheme, where entities can pay for the right to emit one tonne of carbon. Under this scheme it currently costs EUR 56 for the right to emit one tonne of carbon, far higher than the prices quoted by the offsetting schemes.

Nevertheless, using our 0.001 tonnes of carbon emitted per US$ spent on transaction fees estimated in the section above, based on various offsetting prices, one can estimate the premium or extra amount needed to be spent to offset the carbon.

|

Cost to offset one tonne of carbon |

Transaction fee premium |

|

US$5 |

0.5% |

|

US$50 |

5.0% |

|

US$100 |

10.0% |

If an exchange wanted to use the above methodology, assuming a US$50 per tonne cost of carbon, for every US$1 spent on transaction fees, they would need to spend 5 cents offsetting the carbon costs, 5%. A small drop in the ocean compared to the savings available from SegWit, batching and lightning.